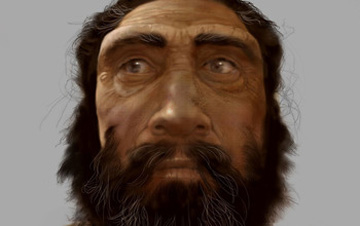

Neanderthals' genetic footprints are evident in humans of today

January 30, 2014

Remnants of Neanderthal DNA found in modern humans are associated with diseases including Type 2 diabetes, Crohn's disease, lupus and cirrhosis of the liver, as well as characteristics that affect cold weather tolerance. These new findings are detailed in a paper published in this week's journal Nature. Harvard Medical School geneticist David Reich is a senior author of the paper and part of a National Science Foundation (NSF)-funded research project that examines how earlier species influence the genetic composition of modern human beings. "This team of geneticists and biological anthropologists is carrying out cutting-edge research on how the genetic makeup of modern humans has been influenced by past species and past events," said Elizabeth Tran, a program manager in NSF's Social, Behavioral and Economic Sciences directorate. "As methods to analyze ancient DNA continue to improve, we are able to get at answers to ever more fine-grained questions about our evolutionary history." The geneticists' findings suggest ways in which Neanderthal DNA present in human genomes today affects disease risk and the production of keratin, the fibrous protein that lends toughness to skin, hair and nails and can be beneficial in colder environments by providing thicker insulation. "Now that we can estimate the probability that a particular genetic variant arose from Neanderthals, we can begin to understand how that inherited DNA affects us," said Reich. "We may also learn more about what Neanderthals themselves were like." In the past few years, studies by groups including Reich's have revealed that present-day people of non-African ancestry trace an average of about 2 percent of their genomes to Neanderthals--a legacy of interbreeding between humans and Neanderthals that the team previously showed occurred between 40,000 to 80,000 years ago. (Indigenous Africans have little or no Neanderthal DNA because their ancestors did not breed with Neanderthals, who lived in Europe and Asia.) Several teams have since been able to flag Neanderthal DNA at certain locations in the non-African human genome, but until now, there was no survey of Neanderthal ancestry across the genome and little understanding of the biological significance of that genetic heritage. Reich and colleagues, including Svante Pääbo of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Germany, analyzed genetic variants in 846 people of non-African heritage, 176 sub-Saharan African individuals, and a 50,000-year-old Neanderthal whose high-quality genome sequence the team published in 2013. The researchers also showed that nine previously identified human genetic variants known to be associated with specific traits likely came from Neanderthals. These variants affect diseases related to immune function and also some behaviors, such as the ability to stop smoking. The team expects that more variants will be found to have Neanderthal origins. The team has already begun trying to improve their human genome ancestry results with colleagues in Britain by analyzing multiple Neanderthals instead of one.

Source of News:

E-mail your news &

photos to editor@sitnews.us

|

|||