What you need to know about the critically endangered whale you’ve never heard ofThe North Pacific right whale is on the edge of extinction but the remaining animals are survivors and may live more than a hundred yearsBy KATIE DOPTIS

February 17, 2017

“Even some people who work in whale research don’t know about [North Pacific right whales],” said scientist Amy Kennedy. “There’s this population of animals that are still alive but are basically going extinct. This is happening now.”

North Pacific right whale

According to Kennedy, North Pacific right whales appear, and act, a lot like their North Atlantic right whale cousins. But genetically the two species are different; scientists believe the animals diverged millions of years ago. North Pacific right whales can grow up to 60 feet long and weigh 100 tons, making them twice as heavy as an average humpback. They mainly feed on small crustaceans called copepods and slowly skim the waters of the ocean to filter their food. The whales have a high-fat content, with a higher blubber to muscle ratio than most other whales. Those basic biological facts, their size, slow speed, and that they float when killed made them whalers’ prime targets. In fact, even their name, “right whale” was coined by hunters who systematically singled them out because they were the right whale to kill, providing an easy bounty of meat and oil. North Pacific right whales were first hunted by “Yankee” (American) whalers in 1835. By 1900, the population had been reduced to a fraction of the original size, according to Center-affiliated researcher Yulia Ivashchenko. “The species was protected by international agreement in 1935 and again in 1946, but we now know that the former USSR killed hundreds of these animals as part of a huge secret campaign of illegal whaling that began after World War II,” she said. Ivashchenko was the first to unearth the details in formerly secret Soviet whaling industry reports she found in archives in Russia. “Right whales were probably making a slow recovery by 1960,” Ivashchenko said. “But the Soviet whalers wiped out the bulk of the remaining population in a few years. We’re still dealing with the legacy of that destruction.” Now, Kennedy and other researchers at the Alaska Fisheries Science Center manage the most comprehensive catalog of North Pacific right whales in the world. The catalog dates back to the 1970s, and some adult whales identified then, are still living today. The whales can be differentiated by callosity patterns -- that is white, raised patches of roughened skin that are found in roughly the same areas of their heads as facial hair occurs in humans. Nobody is sure how long North Pacific right whales live, one would need to document many births and deaths of individual animals to obtain concrete figures. But right whales are closely related to bowhead whales, and evidence suggests bowheads can live more than 100 years. In the database, each whale is given an exclusive code but researchers have also bestowed unofficial nicknames through the years. Notchy, Spot and Smudgy have all been found and documented numerous times; a remarkable feat given the size of the population in relation to the expansive waters where they live.

"Smudgy" plays with a log in the Bering Sea

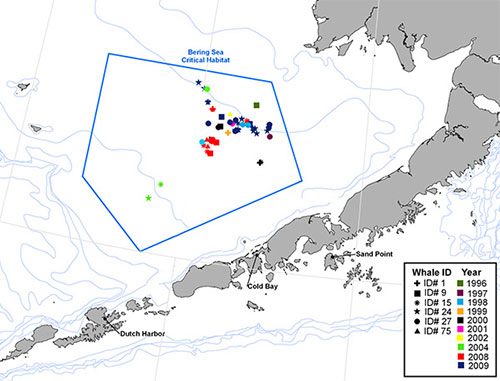

Alaska Fisheries Science Center researchers have made advances in learning about North Pacific right whales. A chance encounter in 2004 by scientists in the Bering to study killer whales led to two right whales being fitted with satellite tags that tracked their movements for about a month. Subsequent research missions in 2008 and 2009 resulted in biological samples and four other right whales being tagged, incredible outcomes that involved a team of scientists who relied heavily on the use of acoustics to detect the whales in the open ocean. The six satellite tags provided months’ worth of data about the whales' movements. From the information collected in 2004, which was a warm year in the Bering Sea, scientists found out right whales swim greater lengths in search of food. Compare that to 2008 and 2009, which were cold, more plentiful years. During that period, the whales concentrated in the southeast Bering Sea, a relief and affirmation to scientists because that area had previously received critical habitat designation under the Endangered Species Act. Critical habitat is an essential area a species needs to survive. For North Pacific right whales, the designation had been made with the best science available. In the Bering Sea, the satellite tags provided confirmation that Center scientists made the correct call when informing regulatory experts.

Map shows right whales' heavy use of a critical habitat area from 1996 - 2009

In addition to surveys, Center scientists collaborate with a network of other researchers and fishermen in the North Pacific who inform them of right whale activity. Unfortunately, there hasn’t been a confirmed sighting of a calf since 2004. “It’s definitely disheartening,” Kennedy said. But she and other scientists like her are doing everything they can to save North Pacific right whales. Informing the world about the whales, their potential loss and what went wrong are a part of that process. “You cannot take things without limits on them. We have a lot to learn from this,” she said. Kennedy also said two of the most important actions people can take are to support endangered animal research and support right whales critical habitat areas, to make sure they are not developed. She still has hope because the remaining animals are “healthy and robust-looking.” Left alone these survivors could become the world’s best recovery story. But first, people need to know North Pacific right whales exist -- spread the word.

Editing by Mary Kauffman, SitNews

Source of News:

Representations of fact and opinions in comments posted are solely those of the individual posters and do not represent the opinions of Sitnews.

|

||