Newly discovered marsupial lived among Arctic dinosaursBy JEFF RICHARDSON

February 20, 2019

The thumb-sized animal, named Unnuakomys hutchisoni, lived in the Arctic about 69 million years ago during the late Cretaceous Period. Its discovery, led by scientists from the University of Colorado and University of Alaska Fairbanks, is outlined in an article published this week in the Journal of Systematic Palaeontology.

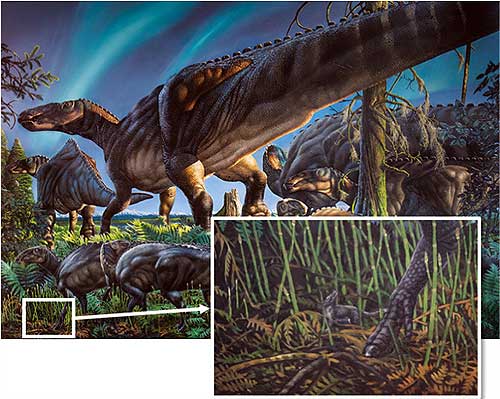

The discovery adds to the picture of an environment that scientists say was surprisingly diverse. The tiny animal, which is the northernmost marsupial ever discovered, lived among a unique variety of dinosaurs, plants and other animals.

Alaska’s North Slope, which was at about 80 degrees north latitude when U. hutchisoni lived there, was once thought to be a barren environment during the late Cretaceous. That perception has gradually changed since dinosaurs were discovered along the Colville River in the 1980s, with new evidence showing the region was home to a diverse collection of unique species that didn’t exist anywhere else. Finding a new marsupial species in the far north adds a new layer to that evolving view, said Patrick Druckenmiller, the director of the University of Alaska Museum of the North. “Northern Alaska was not only inhabited by a wide variety of dinosaurs, but in fact we’re finding there were also new species of mammals that helped to fill out the ecology,” said Druckenmiller, who has studied dinosaurs in the region for more than a decade. “With every new species, we paint a new picture of this ancient polar landscape.” Marsupials are a type of mammal that carries underdeveloped offspring in a pouch. Kangaroos and koalas are the best-known modern marsupials. Ancient relatives were much smaller during the late Cretaceous, Druckenmiller said. Unnuakomys hutchisoni was probably more like a tiny opossum, feeding on insects and plants while surviving in darkness for as many as four months each winter. The research team, whose project was funded with a National Science Foundation grant, identified the new marsupial using a painstaking process. With the help of numerous graduate and undergraduate students, they collected, washed and screened ancient river sediment collected on the North Slope and then carefully inspected it under a microscope. Over many years, they were able to locate numerous fossilized teeth roughly the size of a grain of sand. “I liken it to searching for proverbial needles in haystacks — more rocks than fossils,” said Florida State University paleobiologist Gregory Erickson, who contributed to the paper. Jaelyn Eberle, curator of fossil vertebrates at the University of Colorado Museum of Natural History, led the effort to examine those teeth and a few tiny jawbones. Their analysis revealed a new species and genus of marsupial. Mammal teeth have unique cusps that differ from species to species, making them a bit like fingerprints for long-dead organisms, said Eberle, the lead author of the study.

“If I were to go down to the Denver Zoo and crank open the mouth of a lion and look in — which I don’t recommend — I could tell you its genus and probably its species based only on its cheek teeth,” Eberle said. The name Unnuakomys hutchisoni combines the Iñupiaq word for “night” and the Greek word “mys” for mouse, a reference to the dark winters the animal endured, and a tribute to J. Howard Hutchison, a paleontologist who discovered the fossil-rich site where its teeth were eventually found. Other co-authors of the Journal of Systematic Palaeontology paper include William Clemens, of the University of California, Berkeley; Paul McCarthy, of UAF; and Anthony Fiorillo, of the Perot Museum of Nature and Science.

|

|||||||