Green crab |

Partnerships Expand Effective Management

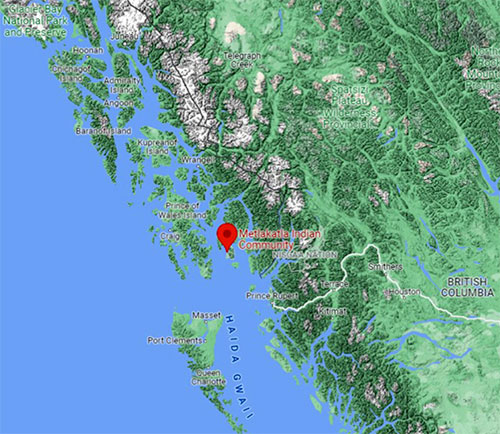

The Department of Fish and Wildlife for the Metlakatla Indian Community, Annette Islands Reserve is leading monitoring efforts to prevent future colonization of the crabs in the area. Part of a green crab shell was found at Haida Gwaii Island off the coast of British Columbia, Canada in 2020. The Metlakatla Indian Community began a passive monitoring program to track any future advancement of the species.

The Metlakatla Indian Community altered their data collection methods in 2021 to deploy passive monitoring traps differently, which made for a more efficient data collection method. The previous year, traps had been set in a line parallel to shore for a complete tide cycle of 24 hours. For 2021, traps were set perpendicular to shore for the same tidal cycle, which was more efficient - areas were accessed more easily and at more locations. This method also gathered data across the shore zone.

The 2021 survey at Annette Island showed no green crabs present. Researchers caught a total of 456 crabs; fortunately all were local and non-invasive species. This was also the first year that surveyors used environmental DNA monitoring. Due to equipment disruption from COVID-19, 10 small-volume seawater samples they collected were sent out for analysis at the NOAA Fisheries lab in Juneau. Analyzing water samples for eDNA will allow the Metlakatla Indian Community to use another tool to detect the presence of green crabs.

Map courtesy NOAA Fisheries |

Adaptive Management

Studies have shown that the green crab’s expansion is hampered by water temperature; however, these constraints are changing as world water temperatures rise. NOAA Fisheries’ partnership with the Metlakatla Community forms a strong defense in monitoring the species’ potential movement into Alaskan waters.

Using adaptive monitoring techniques allows for a robust approach to tracking green crab movements. The Metlakatla Indian Community overcame challenges and built capacity for collecting eDNA samples for crustacean monitoring when faced with shortages due to the pandemic. They discovered that by altering the previous method of trap deployment, they were able to collect more robust data over more representative areas. This implementation of adjusting species monitoring will provide a solid framework for future surveys of Alaskan waters? - hopefully, one without the green crab’s presence.

If all else fails, there is always Maine’s approach of “If you can’t beat ’em, eat ’em," which encourages seafood lovers to eat invasive marine species. Hopefully, Alaska will not have to explore that culinary venture.

The partnership between the Metlakatla Indian Community and NOAA Fisheries advances community interests when faced with invasive species management. By working together, this collaboration is the frontline for detecting the first arrival of green crabs to Alaska waters.

“A green crab emergency has been declared in Washington State due to an exponential increase in numbers that are costing millions of dollars to control infestations. Alaska needs to be vigilant to the threat this species poses to our valuable marine resources,” said Linda Shaw, wildlife biologist with the Alaska Region.

Edited By: Mary Kauffman, SitNews

Source of News:

NOAA Fisheries

www.fisheries.noaa.gov/

Representations of fact and opinions in comments posted are solely those of the individual posters and do not represent the opinions of Sitnews.

Send a letter to the editor@sitnews.us

SitNews ©2022

Stories In The News

Ketchikan, Alaska

Articles & photographs that appear in SitNews are considered protected by copyright and may not be reprinted without written permission from and payment of any required fees to the proper freelance writers and subscription services.

E-mail your news & photos to editor@sitnews.us

Photographers choosing to submit photographs for publication to SitNews are in doing so granting their permission for publication and for archiving. SitNews does not sell photographs. All requests for purchasing a photograph will be emailed to the photographer.