Alaska's yellow cedar considered for endangered species protectionBy MARY KAUFFMAN

April 11, 2015

If listed, yellow cedar would be the first Alaska tree species, and only the second plant in the state, protected by the Endangered Species Act. According to an earlier U.S. Forest Service Report, yellow cedars (Calliptropsis nootkatensis) are killed as the climate changes, with spring temperatures warming and snow cover being more frequently insufficient to protect the roots. A lack of snow exposes this species’ shallow, fragile roots to freezing temperatures that can kill them.

Yellow cedar cones and foliage. Also known as Calliptropsis nootkatensis. Behind are subalpine fir trees.

Conservationists say that despite the trees’ decline, timber sales in the Tongass National Forest selectively target remaining living yellow cedars because of the wood’s unusual qualities and its exceptionally high market value. They hold massive amounts of the greenhouse gas carbon dioxide, and their extinction would be a devastating loss say conservationists. Rebecca Noblin, Alaska director at the Center for Biological Diversity, said. “Yellow cedars have joined the long line of species headed for extinction because of the climate crisis.” Nobli said, “These trees are tough and have survived where others can’t, but all their unique defenses are useless against a warming climate. The Fish and Wildlife Service must protect yellow cedars immediately so we can turn this around.” Ketchikan resident Owen Graham, the Executive Director of the Alaska Forest Association told SitNews the USFS silviculture people in Alaska have explained that yellow cedar decline is an intermittent phenomenon that occurs on some bog-like sites sporadically every 20-years or so. Owen said, "We know of no researcher who has used the word ‘extinction’ for the current or even future yellow-cedar health or viability issue in Alaska." He added, "Through selective thinning and occasionally planting, we actively manage for yellow-cedar on lands we’ve harvested in the past where yellow-cedar occurs. As a result, yellow-cedar is thriving in many of our managed stands." Owen explained that the decline occurs in very poor, wet sites where the trees are barely surviving to start with. The hypothesis is that the roots are killed by cold weather during low snow years. It does not seem to affect yellow cedar in the majority of the forest and it does not usually kill all the trees in the affected sites. Also, the new growth in the affected sites seems to be growing normally. Southeast Alaska is at the current northern extreme of the yellow cedar range, said Owen, but that range has been trending northward since the glaciers receded thousands of years ago. Most species at the fringe of their range typically are less abundant and trees at the fringe of their range typically have trouble competing with other trees. Greenpeace forest campaigner Larry Edwards has a different opinion. Sitka-based Edwards said, Edwards said, “A Forest Service report acknowledges that Tongass timber sale planners select project areas with a higher than average cedar component and plan timber projects that extract cedar at a higher rate than its occurrence in the project areas.” Edwards said, “For example, while yellow cedar is 9.5 percent of the growing stock on the south Tongass, it is 17 percent of the timber volume in the controversial Big Thorne project.” Conservationists say Vast swaths of yellow cedars have died off in the past century, with more than 70 percent of these long-lived, beautiful trees now dead in many areas of Alaska. “There is a double perverse incentive for the Forest Service to log yellow cedar disproportionately to its natural occurrence — that is, to high-grade it,” said David Beebe, president of the Greater Southeast Alaska Conservation Community. “First, this species has exceptionally high market and stumpage values. Also, by law the agency cannot offer timber sales that appraise to a negative sale value, and boosting the proportion of high-value cedar in a timber sale is a way to overcome that.” “When we first started offering nature-based wilderness cruises in southeast Alaska 35 years ago,” said Joel Hanson of The Boat Company, “the region’s predominant mixed-conifer slopes generally looked healthy, with only a few dead-standing yellow cedars in evidence here and there. But now we see mile after mile of slopes where almost all the yellow cedar trees are dead. We should be protecting remaining healthy stands of this species wherever they may still be found in the region, not clearcutting them.”

Yellow-cedar in West Chichagof-Yakobi Wilderness Area, Date: 2012. The West Chichagof-Yakobi Wilderness Area is a pristine area of coastal Alaska. The West Chichagof-Yakobi Wilderness is part of the Tongass National Forest, the largest national forest in the United States

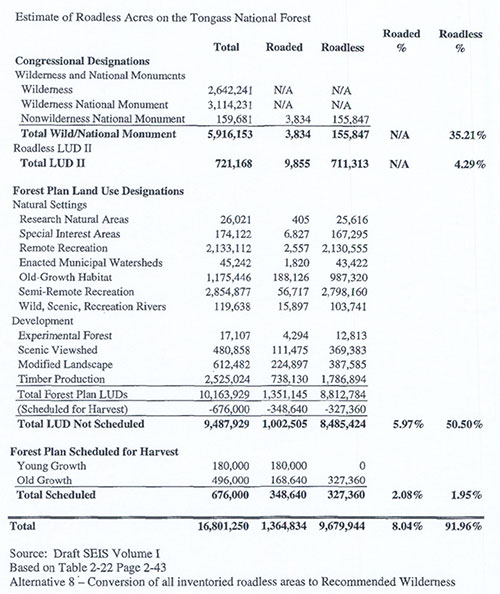

Supporters of designating the yellow cedar as endangered say if greenhouse gas emissions continue to rise at their current rates, the tree will be driven to extinction. Reducing greenhouse gas emissions, while at the same time eliminating any live-tree harvest by logging, is the yellow cedar’s best hope for survival. Owen added that although this issue is interesting, it is insignificant in comparison to the rest of the forest. In order to provide further clarification he noted:

Owen said, "The yellow cedar trees are not an endangered species. Even if the global warming hypothesis is correct, it might adversely affect only some of the yellow cedar trees in some of the non-commercial, bog-like stands." According to this 2007 Forest Service chart provided by Owen, there is no shortage of timber on the Tongass; yellow cedar or other species. 2007 Forest Service chart

The petition to list the yellow cedar was filed by the Center for Biological Diversity, The Boat Company, the Greater Southeast Alaska Conservation Community and Greenpeace in June 2014. Comments due by June 09, 2015. You may submit comments for which a status review is being initiated by one of the following methods:

Docket Folder:

On the Web:

Sources of News:

|

||