The ore body containing graphite is shown in this 2021 photo of Graphite Creek. At far left is a Graphite One drill rig. |

“Knowing that can help with exploration,” he said.

The United States extracts no graphite of its own. The nation imports one-third of its graphite from China, with Canada and Mexico among other suppliers.

The federal government has listed graphite as a critical mineral.

The researchers’ findings can guide development of Graphite Creek by Graphite One, the company behind the mining project. The Federal Permitting Improvement Steering Council in January 2021 designated Graphite Creek as a high-priority infrastructure project.

A research paper published Feb. 27 in the journal Mineralium Deposita defines the age and characteristics of the deposit and provides information geologists can use to understand other potential graphite sites.

George Case of the U.S. Geological Survey in Anchorage is the paper’s lead author. Regan is among the eight co-authors.

Geologists have had little understanding of the processes that lead to creation of high-grade flake graphite. That lack of understanding has been a barrier to evaluating such deposits for exploration and development.

“To really understand the system, you need to understand everything that’s going on. You need to incorporate tectonics, timing, petrology and structural geology,” Regan said. “All of those things need to make sense together because it’s a system.”

The Graphite Creek deposit is 37 miles north of Nome in the Kigluaik Mountains and is approximately 3 miles long and one-tenth of a mile wide. The Kigluaik Mountains formed in the Late Cretaceous Period, 100 million to 66 million years ago. They include the Kigluaik gneiss dome.

|

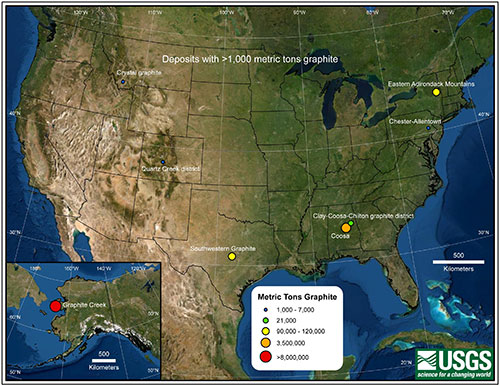

The map shows sites with more than 1,000 metric tons of contained graphite resource or past graphite production or both. This is approximately 3% of the average annual U.S. consumption of graphite between 2016 and 2020. |

To reach their current graphite-rich state, the deposit’s rocks partially melted between 92 million and 97 million years ago in a process called biotite dehydration melting. The process removes up to 30% of a rock’s material as liquid, leaving a graphite-heavy solid along with other solids formed during the partial melt reaction. The liquid flows away.

Through analysis of core samples provided by Graphite One, the researchers established the first criteria for determining the likely presence of concentrated flake graphite. These criteria can now be used to evaluate other regions suspected of holding graphite:

- The presence of original carbon-rich sedimentary rock deposited in water that didn’t contain dissolved oxygen.

- Evidence of high-temperature metamorphism such as the presence of potassium feldspar and sillimanite.

- Evidence of partial melting such as through the presence of migmatites, which are rocks containing metamorphic rock and igneous or igneous-appearing rock.

“The key here is this anatexis, or partial melting, which has removed silicate material and thereby concentrated the graphite,” said Case, the research paper’s lead author.

The Graphite Creek deposit, and the Seward Peninsula, are within the Arctic Alaska-Chukotka microplate. That region also includes Alaska’s Brooks Range and Russia’s Chukotka, where the presence of similar geologic characteristics could indicate additional flake graphite deposits.

This article is provided as a public service by the University of Alaska Fairbanks's Geophysical Institute and at the UAF College of Natural Science and Mathematics. Rod Boyce [rcboyce@alaska.edu] is a science writer with the Geophysical Institute. |

Representations of fact and opinions in comments posted are solely those of the individual posters and do not represent the opinions of Sitnews.

Send a letter to the editor@sitnews.us

SitNews ©2023

Stories In The News

Ketchikan, Alaska

Articles & photographs that appear in SitNews are considered protected by copyright and may not be reprinted without written permission from and payment of any required fees to the proper freelance writers and subscription services.

E-mail your news & photos to editor@sitnews.us

Photographers choosing to submit photographs for publication to SitNews are in doing so granting their permission for publication and for archiving. SitNews does not sell photographs. All requests for purchasing a photograph will be emailed to the photographer.