Women earn an average of 68 percent of what men make in Alaska

July 09, 2017

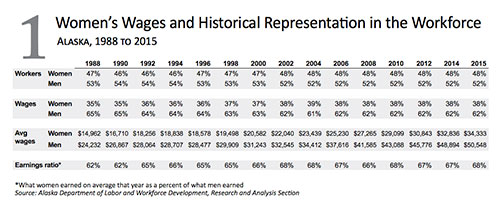

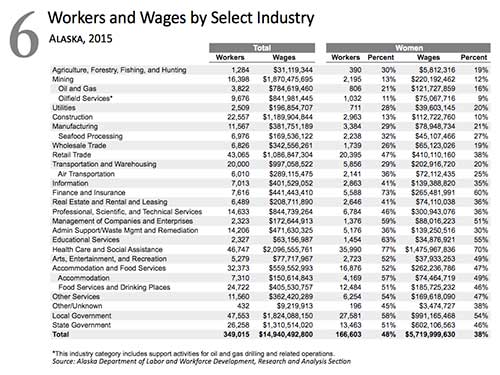

In 2015, nearly 167,000 women worked in Alaska and earned $5.7 billion. However, according to Wiebold, men earn more in nearly 80 percent of Alaska’s occupations and at every age and educational level, even though men and women participate in the workforce at nearly equal rates and work the same number of quarters per year. Forty-eight percent of the state’s workers were women in 2015, but they made 38 percent of total wages.

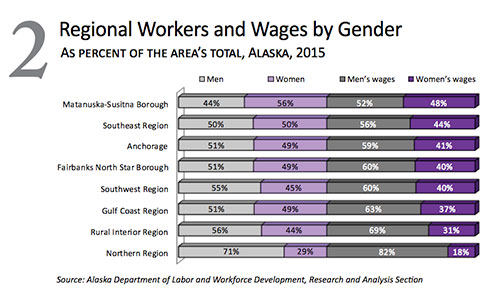

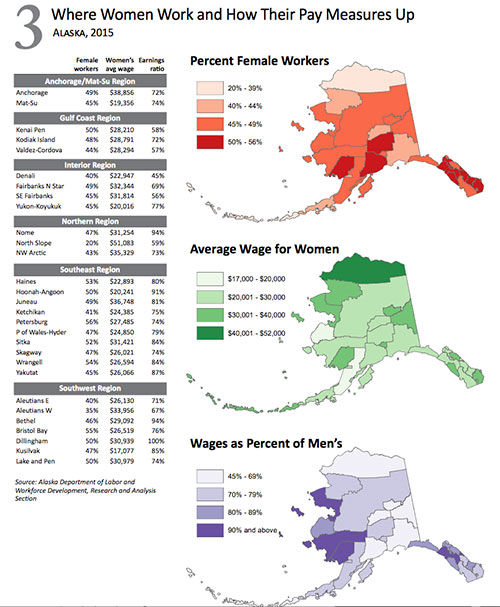

In a recent article published in the Alaska Economic Trends magazine, Wiebold reported that women’s workforce presence and share of total wages have both increased slightly since the late 1980s, when women were 47 percent of workers and earned 35 percent of wages. But over the past decade, both percentages have stayed about the same, with wages hovering around 38 percent and the percent of total workers varying by just half a percentage point. The earnings ratio, or women’s wages in Alaska as a percent of men’s, has grown somewhat over time reported Wiebold an economist. During the late 1980s, when Alaska was recovering from a significant recession, wage parity was at a low of 62 percent. That gap narrowed during the 1990s, to between 65 and 66 percent, and it continued to shrink into the 21st century. Wiebold's article’s data did not measure the reasons for the Alaska's gender wage gap. She suggested there were a variety of factors likely influence the disparity in wages, including job experience, training, education, hours worked, choice of occupation or industry, and current and historical discrimination - but the degree to which those factors affect the gap was outside her article’s scope. Gap smallest in urban areas While women are 48 percent of the workforce statewide, the percentage varies considerably by region wrote Wiebold. The percentages in some of the most populated and urban areas - Anchorage, Fairbanks, and the Gulf Coast - are around 49 percent. Women earn a slightly higher percentage of wages than the statewide 38 percent in the two most urban areas: Anchorage (41 percent) and Fairbanks (40 percent). Those cities have a significant number of high-paying private occupations as well as state and local government jobs, which have a smaller wage gap.

According to data presented by Wiebold, in Southeast Alaska, women make up 50 percent of the workforce and how their pay measures up differs by location, such as:

The Gulf Coast Region’s workforce is 49 percent female, but women earn just 37 percent of total wages reported Wiebold. The area is notable for its high-paying jobs in oil and gas, the industry in which women are least likely to work. Rural areas with remote work sites, such as the Northern and Rural Interior regions, have higher percentages of men in the workforce according to Wiebold. Mining, oil extrac on, and oilfield services workers are predominantly men, and those jobs are also high-wage. For example, the North Slope Borough, where women earn 59 percent of what men make on average, has a workforce that’s just 20 percent women. Note, however, that the women who work in the North Slope Borough have the highest average wages in the state.

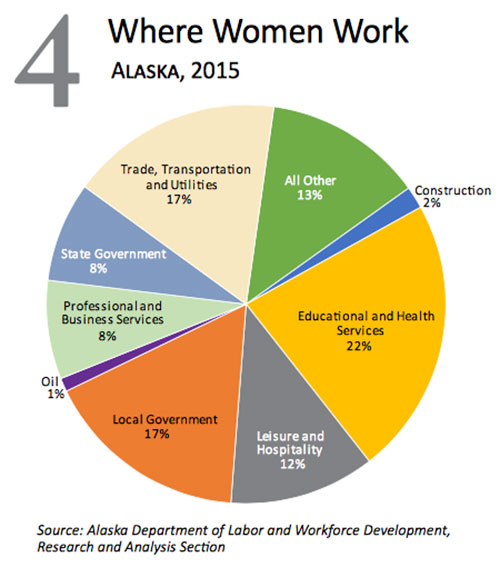

Other rural areas where local government is a larger slice of the economy tend to have a smaller gap because men and women in these jobs make similar wages. The Matanuska-Susitna Borough has the workforce with the highest percentage of women, at 56 percent. Unless otherwise noted, all numbers in this ar cle are for the place where people work rather than where they live, and many Mat-Su residents work outside the borough. Nearly 13,000 work in Anchorage, where average wages are higher, and 62 percent of those commuters are men. Of the 3,449 Mat-Su residents who commute to the North Slope, 90 percent are men, as are 70 percent of the nearly 500 who commute to Kenai. Concentrated in health care and local government According to Wiebold, women work in every industry in Alaska but are concentrated in a few. Nearly one in four women work in private educational and health services, which include health care workers but not public school teachers. The second largest industry groups for women are local government, which includes teachers; and the trade, transportation, and utilities group, which includes retail workers.

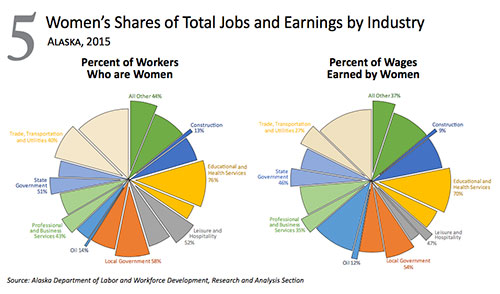

Oil and construction, industries with high average wages, have the smallest shares of women. Just 3 percent of Alaska's female workers are in those industries. Women in Alaska make up more than half of workers in education and health services, leisure and hospitality, and state and local government. (See Exhibit 5.) They are the minority in construction; oil; professional and business services; and trade, transportation, and utilities, reported Wiebold.

In all major Alaska industry groups, women earn proportionally less than men do. Although women in Alaska make up 77 percent of health care and social assistance, for example, they bring home 70 percent of the wages.

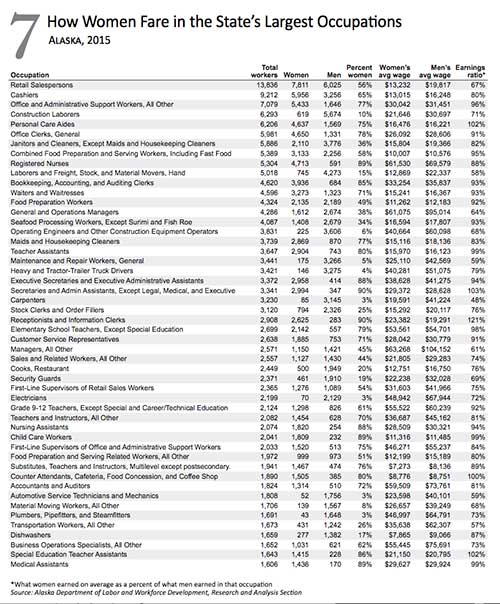

Gap smaller in occupations with more women As with industries, women are much more likely to work in some occupations than in others. Women are the majority in 29 of the 50 largest occupations, ranging from a high of 90 percent in white-collar positions such as receptionists and information clerks, secretaries, and administrative assistants to a low of 3 percent in blue-collar occupations such as electricians, automotive service techs, mechanics, carpenters, plumbers, pipefitters, and steamfitters.

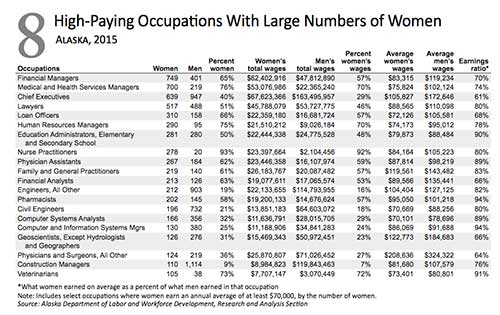

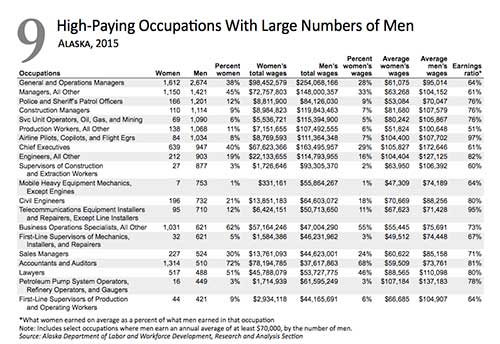

According to Wiebold's data, generally, the higher the percentage of women in an occupation, the smaller the wage gap. But while the wage gap is smaller in those occupations, the overall wages are lower, with registered nurses and school teachers being two exceptions. More men in Alaska work in high-wage jobs Fewer women work in high-wage occupations, and those who do earn less than men in those jobs reported Wiebold. Out of more than 700 occupations in Alaska, 81 pay women an average of $70,000 a year or more, while twice as many occupations pay men at least that much.

High-wage occupations for women employed 7,374 women in 2015. Men out-earned women in these jobs, making an average of $120,000 versus $93,000 for women. In the 168 occupations where men earned at least $70,000, women made up just over a third of those workers and earned an average of $29,000 less, reported Wiebold. According to Wiebold, Alaska women earn more than men in about 20 percent of the 700 occupations, some of which include special education teachers and assistants, receptionists and information clerks, and personal care aides.

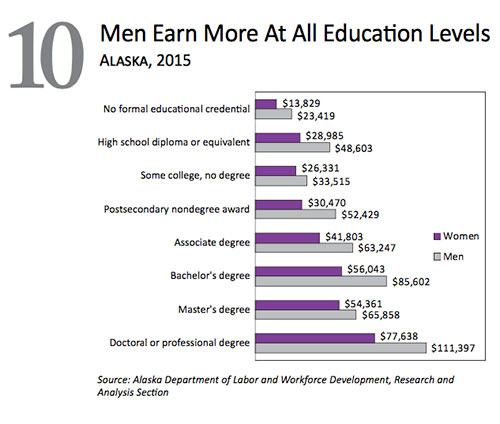

Men earn more at every education level in Alaska Men earn more at every level of education required for employment, reported Wiebold, and the percentage gap is largest in jobs with minimal education requirements. About two-thirds of Alaska’s workers hold jobs that require a high school diploma or less. At the other end of the spectrum, about 20 percent have jobs that require a bachelor’s degree, and less than 5 percent are in jobs requiring a master’s or doctorate.

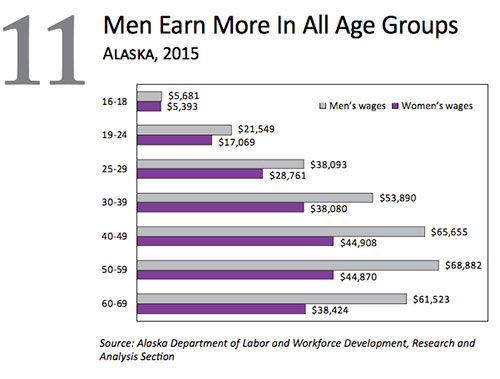

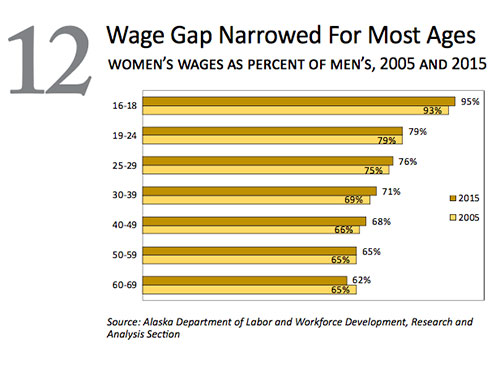

Jobs with no formal education requirement pay men an average of $9,590 more per year than women - an earnings ratio of 59 percent. When a high school diploma or Much of the discrepancy in pay, according to Wiebold, is due to the jobs they hold. Most men whose jobs require a diploma or less hold low-paying positions such as retail salespeople ($20,000), construc on laborers ($31,000), hand laborers ($22,000), and janitors and cleaners ($19,000). However, a significant number earn high wages in oil field and construction occupations such as petroleum pump systems operators ($137,000), service unit operators in oil, gas, and mining ($106,000), production workers ($101,000), and first line supervisors of construction trades and extraction workers ($106,000), which increases their average. Women in jobs with minimal education requirements work almost entirely in the lower-paying occupations, according to Wiebold. Her data shows 3,956 men in jobs that require minimal education average more than $100,000, but only 26 women. The largest numbers of women were retail salespeople ($13,000), cashiers ($13,000), office and administrative support ($30,000), office clerks ($26,000), and personal care aides ($16,000). At the upper end of the education spectrum, jobs requiring a doctoral or professional degree pay the highest wages to both men and women but there's an earnings ratio of 70 percent, which is a larger gap than for master's degrees but smaller than for bachelor's degrees. The largest numbers of women in Alaska with doctoral or professional degrees work as lawyers ($89,000), physical therapists ($62,000), family and general practioners ($120,000), pharmacists ($95,000), and postsecondary teachers ($26,000). The top occupations for highly educated men in Alaska include lawyers ($110,000), physicians and surgeons ($324,000), postsecondary teachers ($23,000), postsecondary business teachers ($42,000), and pharmacists ($101,000). Age matters for wage parity Men in Alaska also out-earn women in Alaska at every age, and the wage gap increases by age group reported Wiebold. For teenagers between 16 and 18, the earnings ratio is 95 percent, although wages are low for both genders. At these ages, workers are mostly limited to low-paying summer jobs, largely in food preparation and serving or sales. It’s also the only age group with more female workers than males. Among older workers, men are generally 52 to 53 percent of Alaska workers.

For older workers in Alaska, the wage gap increases with shifts in their hours, education, and occupational choices. Women’s earnings peak and then plateau between the ages of 40 and 50, while men’s earnings peak between 50 and 60. While the wage gap shrunk or held steady for most age groups over the past decade, it increased by 3 percentage points in the 60-to-69 group, where the gap is also largest. That age group is also the fastest growing. The number of older workers in Alaska more than doubled between 2005 and 2015, from 14,887 to 30,812. Wiebold's data showed that older men in Alaska tend to work in construction and extraction ($59,000), management ($115,000), and transportation and material moving occupations ($50,000). Older women in Alaska work largely in office and administrative support ($35,000) and educational instruction and library occupations ($33,000). Older workers have maintained similar occupation concentrations as in the past, but for some of the occupations - such as those in construction and extraction, educational instruction and libraries, and office support - older men’s average wages increased more than women’s.

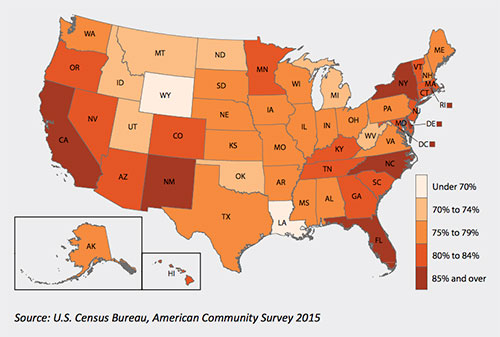

How Alaska Compares Nationally National data sources, such as the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics’ Current Population Survey and the U.S. Census Bureau’s American Community Survey, differ significantly from Wiebold's article in that both are survey-based, use median wages instead of the average, and limit data to full-time workers. While using different sources changes the size of the gap, they all tell the same story: that women earn significantly less than men and that Alaska ranks lower than the nation overall and lower than most states, even though Alaska has higher average wages for both men and women. According to the U.S. Census Bureau’s American Community Survey, Alaska ranks 33rd for wage parity, with women earning a median wage that’s 78 percent of what men make: $43,455 and $55,752, respectively. New York and Delaware top the list with earnings ratios of 89 percent, and Wyoming comes in last at 64 percent. Nationwide, the earnings ratio is 80 percent, with $39,940 in average annual earnings for women and $49,938 for men.

About the gender wage gap and limitations of the data The difference between women’s and men’s wages is referred to as the gender wage gap, and it can be influenced by a number of factors, including experience, training, educa on, hours worked, job and industry choice, and discrimina on. A wide variety of studies have a empted to measure and explain the reasons for the wage gap, but that type of analysis is outside the scope of this ar cle. For her article, Economist Karinne Wiebold, examined the total wages earned by each gender and the difference in their average annual wages. (Women’s average wages divided by men’s is also called the earnings ratio.) Staff matched occupational data the Alaska Department of Labor and Workforce Development collects through the state’s unemployment insurance program with demographic data from Permanent Fund Dividend applications. These two sources allow a range of comparisons, but Wiebold reported they have some major limita ons. The biggest drawback is they don’t allow us to differenate between full-time and part-time or seasonal workers, and including part-time and seasonal workers brings down the average for yearly wages. Second, because staff included only those who were eligible for unemployment insurance and applied for a dividend, this analysis doesn’t cover nonresidents, who make up about 20 percent of the state’s annual workforce. It also excludes those who didn’t specify a gender, the self-employed, and federal civilian and military workers. For a more useful analysis in the occupation-specific section, department staff considered only the occupation in which a worker made the most money, which understates total wages for people who held more than one job. For example, if Mary worked as a teacher but also held a summer retail job, her occupation would be “school teacher” and only those wages would be considered. However, in this article’s broader analysis, such as for overall workers and wages, her retail wages would also be counted.

Representations of fact and opinions in comments posted are solely those of the individual posters and do not represent the opinions of Sitnews.

|

||||||||||||||||