Study ranks marine mammals’ risks from Arctic shippingBy HEATHER MCFARLAND

July 06, 2018

The study is the first to assess the vulnerability of the seven marine mammal species that could encounter more vessels as the ice-free season expands in Arctic seas. The study, produced by researchers at the University of Alaska Fairbanks and the University of Washington, was published July 2 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

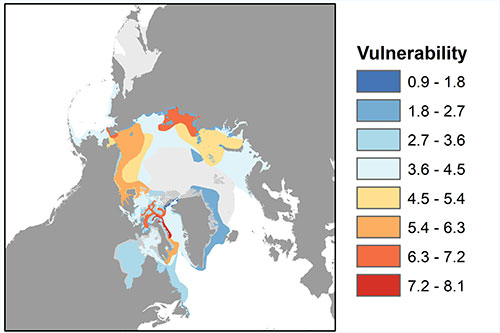

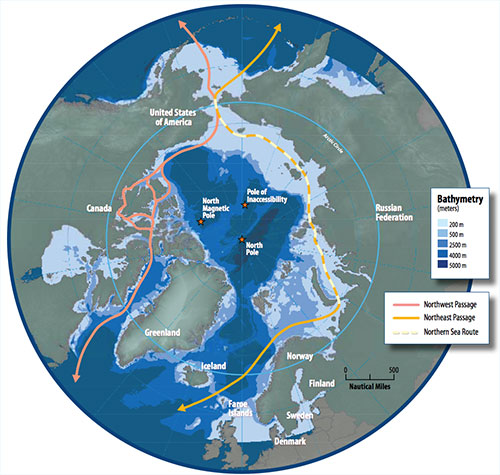

In recent decades, parts of the Arctic seas have become increasingly ice-free in late summer and early fall. As sea ice is expected to continue to recede due to climate change, seasonal ship traffic from tourism and freight is projected to rise. “We know from more temperate regions that vessels and whales don’t always mix well, and yet vessels are poised to expand into this sensitive region,” said lead author Donna Hauser, who worked on the study as a UW postdoctoral researcher and is now a UAF research assistant professor. “Even going right over the North Pole may be passable within a matter of decades. It raises questions of how to allow economic development while also protecting Arctic marine species.” The study looked at 80 subpopulations of the seven marine mammals that live in the Arctic. It identified risks on or near major shipping routes in September, a month when Arctic seas have the most open water.

Forty-two subpopulations would be exposed to vessel traffic. The degree of exposure and the particular characteristics of each species determine which are most sensitive. Across the Arctic, the most vulnerable marine mammals are narwhals, or tusked whales. These animals migrate through parts of the Northwest Passage, the northern waterway linking the Atlantic and Pacific oceans.In Alaska, bowhead whales are the most vulnerable, followed by populations of walruses and beluga whales. Given their size, speed, and surface-oriented behavior, bowhead whales are considered more sensitive to vessel strikes than the other seven Arctic marine mammals, which was one factor determining vulnerability. The subpopulation in the Bering, Chukchi and Beaufort seas is the most exposed to the sea routes and therefore is more vulnerable than other bowhead populations. Walruses also are vulnerable because some populations are relatively small and live along shipping routes. Other studies also suggest they are sensitive to disturbance. Ringed and bearded seals, with generally large and widely distributed populations, are less vulnerable. Least vulnerable to vessel traffic were polar bears, which are largely on land in September and don’t rely on underwater sound for communication or navigation. Shipping in other seasons may have a greater impact on the species, and previous research suggests sea ice loss will affect polar bears in other ways.

The paper also identified two “pinch points,” narrow passageways where ships and animals are most likely to intersect. These are Lancaster Sound in the northern Canadian territory of Nunavut, and the Bering Strait, which separates the U.S. and Russia. These regions had a risk of conflicts two to three times higher than on other parts of the shipping route. The Bering Strait is a necessary pathway for vessels using both the Northwest Passage and the Northern Sea Route, a path along Russia’s Arctic coast. It was, until recently, impassable by unescorted commercial vessels. The strait is also critical to several populations of belugas, seals, bowheads and walruses migrating in and out of the Arctic. “These species are critical traditional resources for coastal Alaska communities,” Hauser said. “Increased vessel traffic in this region is just one of many significant recent changes that have the potential to impact marine mammals but also the people that rely on them.”

Travel through the Arctic is already beginning. In August 2016, the first large cruise ship traveled through the Northwest Passage. The following year, the first ship without an icebreaker plied the Northern Sea Route. The Northern Sea Route has the most potential for commercial ships. However, more than 100 vessels using the Northwest Passage passed through the Bering Strait from 2011 to 2016. More than half were small, private vessels like personal yachts. The International Maritime Organization in May established the first international guidelines for vessel traffic in the Arctic Ocean. The voluntary code was proposed by the U.S. and Russia to identify safe routes through the Bering Strait. This action and studies like Hauser’s are necessary steps in developing safe shipping measures in the Arctic. “Identifying the relative risks in Arctic regions and among marine mammals can be helpful when establishing strategies to deal with potential effects,” said Hauser. The study will help to bolster future guidelines, prioritize different measures to protect marine mammals and identify areas needing further study. “We could aim to develop some mitigation strategies in the Arctic that help ships avoid key habitats, adjust their timing taking into account the migration of animals, make efforts to minimize sound disturbance, or in general help ships detect and deviate from animals,” said co-author Kristin Laidre, a polar scientist at UW Applied Physics Laboratory’s Polar Science Center. The study was funded by NASA and the Collaborative Alaskan Arctic Studies Program. The other co-author is Harry Stern, a polar scientist at the University of Washington Applied Physics Laboratory.

Representations of fact and opinions in comments posted are solely those of the individual posters and do not represent the opinions of Sitnews.

|

|||||||