Ketchikan’s Fluid Economy: Alaska’s gateway city, from mining and timber to fishing and tourismBy CONOR BELL

August 16, 2014

In the late 19th century, white settlers explored the southern part of the Southeast panhandle in search of a place to harvest salmon. They found the mountainous land undesirable until they discovered the mild sloping beach surrounding the Kitschkin stream, where the Tlingits had established a summer fish camp.

A panorama of downtown Ketchikan on a sunny day. Ketchikan averages 229 days of

Mining in the early days Mining became dominant in the area during the Alaska Gold Rush, and Ketchikan was many pros- pectors’ first stop on their trip north. The town also served as a supply center for mines operating in the surrounding area and on Prince of Wales Is- land, mines that produced some gold but primarily focused on copper. By 1900, the town had grown to approximately 800 people. When the stock market and copper prices tumbled in 1907, area mines closed. Fishing helped compen- sate for the loss of jobs, and more canneries were built in the years that followed as a market devel- oped for shipping frozen salmon and halibut. Logging also gained prominence and became the economy’s driving force for most of the 20th century.

Ketchikan Creek runs along Ketchikan's historic Creek Street, a boardwalk on pilings.

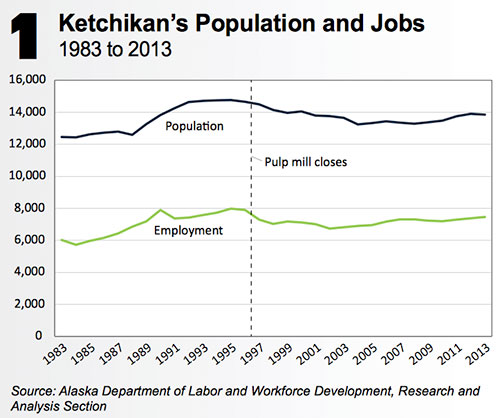

Until the early 1900s, a few small logging companies provided lumber locally, but the majority of lumber the town used was shipped in. Ketchikan Spruce Mills opened in 1903, nearly filling local demand for lumber and remaining in operation until 1983. Ketchikan Pulp Company opened in 1954, processing lumber harvested from the Tongass Na- tional Forest. In 1989, the pulp mill was the state’s seventh-largest private employer, and it was consistently one of the 20 largest private employers through the mid-1990s. With the timber industry flourishing, Ketchikan’s population peaked in 1995 at approximately 14,800 people.

The mill, which had been cited for violating air and water emission laws and paid several million dollars in penalties, was closed in 1997 partly because it needed hundreds of millions of dollars in environmental renovations. The company continued logging on Forest Service land for two more years.

Since then, the Ketchikan Gateway Borough’s population has risen to 13,900, which includes the city’s population of 8,300, the nearby Native village of Saxman with 411 people, a census- designated place called Loring with a population of three, and 5,129 who live outside of any defined city or CDP.

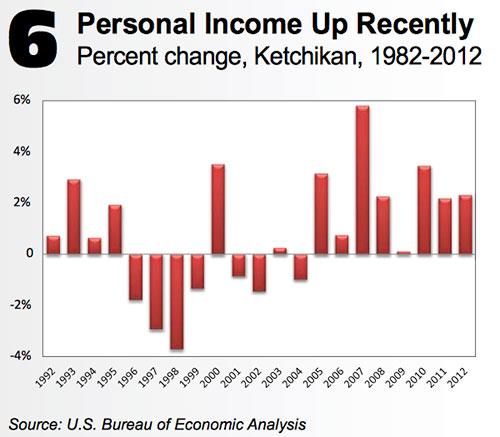

Ketchikan’s average annual wage in 2013 was $42,767, considerably below the statewide aver- age of $51,033. The average wage doesn’t paint a complete picture, though, as it doesn’t include fish harvesting income or account for people working multiple jobs. For example, if a person spends the summer work- ing in retail and the rest of the year working for the school district, wages at each employer would be counted separately, effectively lowering the average wage. Many jobs in the borough are seasonal, such as those in tourism and seafood processing. Personal income is a closer estimate of how much the average resident makes in a year, as it includes not just wages from a job but all the money a person takes in, such as investment income and transfer payments (for example, Social Security, retirement, and public assistance). It also factors in income from multiple jobs and self-employment, including fish harvesting. (see Exhibit 6)

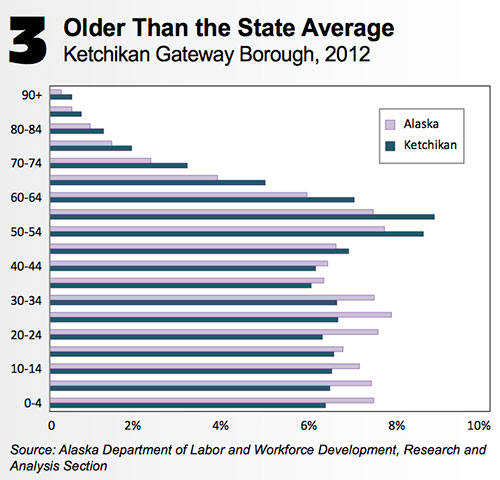

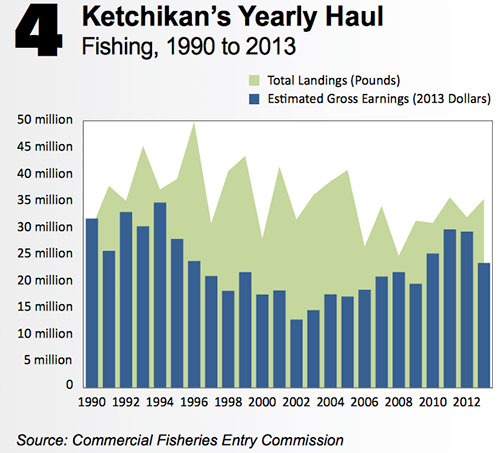

Though the average wages per job are lower in Ketchikan, the area has more jobs per capita than the state as a whole as well as a higher level of business ownership income. Ketchikan also has 21 percent higher per capita transfer payments than the state as a whole, in this case mainly driven by the retirement income of an older population (see Exhibit 3) and dividends, interest, and rents. A different mix of industries today Forestry and logging remains a minor industry in Ketchikan, comprising four firms with an average monthly employment of 59 in 2013 and $3.5 mil- lion in total wages. Although the population hasn’t recovered its his- toric highs, and minor losses are projected over the next 15 years, Ketchikan’s economy has adapted and developed renewed strength. Fishing the economic mainstay A welcome sign hanging over Mission Street in downtown Ketchikan proclaims the town “The Salmon Capital of the World.” Fishing has given Ketchikan’s economy resilience through the disappearance of mining in the early 1900s and the logging decline of the 1990s. Still, it’s an inherently volatile industry, and earnings can fluctuate greatly from year to year depending on landings and price.

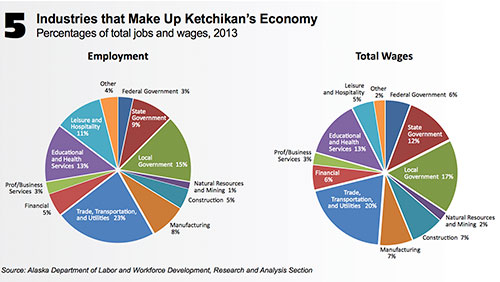

Alaska salmon prices have remained high, and The Southern Southeast Regional Aquaculture Association runs two hatcheries in the Ketchikan area to keep the salmon supply relatively stable. Although fish harvesters are vital to Ketchikan’s economy, they don’t show up in regular employ- ment statistics because they’re self-employed and not subject to the same reporting requirements as other workers. Because they aren’t included in this article’s numbers, alternate measures are necessary to quantify fishing’s impact on the economy. The Commercial Fisheries Entry Commission estimates Ketchikan borough residents fished 344 permits in 2013, resulting in $23.4 million in gross income. In 2012, National Oceanic and Atmospheric As- sociation estimated Ketchikan’s fishery landings at 74 million pounds, making it the eighteenth-largest port in the U.S. by quantity. NOAA also ranked the value of Ketchikan’s port eight-teenth in the nation that year, at $54 million. Manufacturing primarily in seafood processing Another indicator of fishing’s role in the economy is its seafood processing. The first industrial building in Ketchikan was a cannery, and seafood processing continues to be a primary economic driver. In August 2013, food manufacturing provided 1,226 jobs, making up 13 percent of em- ployment that month. The industry is highly seasonal, though, and average employment in food processing for the year was 444, or 6 percent of all jobs. In 2013, six nonfood manufacturing firms provid- ed another 152 jobs. These firms produced goods such as transportation equipment, wood products, and fabricated metal products. The largest, Alaska Ship and Dry Dock, had more than 100 employees and a $31 million, 70,000-square-foot assembly hall. All manufacturing-related jobs, food and otherwise, paid a total of $23.8 million in wages during 2013 - 7 percent of total wages. Click on the graphic to view a larger image.

Another major piece of Ketchikan’s economy is government, making up about 28 percent of jobs in the borough. These jobs tend to be higher-paying, so the government share of total wages is higher, at roughly 34 percent. Ketchikan is home to Alaska Marine Highway System headquarters and a University of Alaska Southeast campus, which contribute to a bigger state government presence than Alaska’s average. The city’s percentage of local government jobs is also above the state average, largely due to the Ketchikan Indian Community. The tribe also oper- ates a large health clinic. While tribal government is always included in local government job totals, these tribal health jobs are counted as private- sector employment in Ketchikan and many other Alaska communities. City a major tourist port Ketchikan is the first port for most cruise ships visiting Alaska, and as the cruise industry grew through the 1990s and early 2000s, visitor-related employment became more important to the economy. Ketchikan had an estimated 935,900 visitors in summer 2012, over 90 percent of whom arrived by cruise ship. Jobs in visitor-related industries averaged 1,171 in 2013, fluctuating from a low of 716 in February to 1,823 in July. Ketchikan’s visitor industry has a unique blend of jobs compared to U.S. tourism overall; for example, jobs in scenic and sightseeing transportation are 103 times more common in Ketchikan than the U.S. as a whole.

The city is also a hub for people traveling to and from Prince of Wales Island, now a popular fishing destination with a population of approximately 6,000. The borough’s status as a regional hub means its percentage of air transportation jobs is eight times higher than the U.S. average. Nearby mining prospects Mining led to the initial boom in Ketchikan’s population, and it has the potential to become a driving force again. No mines currently operate in southern Southeast Alaska and there’s little short-term poten tial for development of a mine in Ketchikan Gate- way Borough. However, a few major sites on Prince of Wales Island are in exploration phases. If the sites go into production, many of the jobs and service-providing demands could fall to Ketchikan workers and businesses, and Ketchikan businesses have already provided support services to the projects. The Niblack Project, located 27 miles from Ketchikan on southeast Prince of Wales, is in the advanced exploration phase. Heathedale Resources reports spending $37 million on exploratory drill- ing since 2009 and finding significant deposits of copper, gold, zinc, and silver. The Alaska Legislature has authorized the Alaska Industrial Develop- ment and Export Authority to provide bonds of up to $135 million for development of the project. The Bokan Mountain Project is located on south- ern Prince of Wales Island. Ucore Rare Minerals has completed a preliminary economic assessment and is in the middle of a feasibility study. Ucore focuses on extracting rare earth elements - primarily dysprosium, terbium, and yttrium - and the U.S. Department of Defense has contracted with the company to purchase them if the project advances to production. The Legislature has also authorized AIDEA to provide $145 million in bonds for the project.

Conor Bell, an Alaska Department of Labor economist in Juneau, specializes in the employment and wages of the Southeast and Southwest economic regions.

|

|||