By Dave Kiffer September 19, 2006

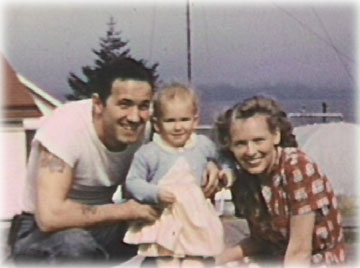

Waugh was the young daughter who lived on the island with her parents, Dan and Alline Moore from 1952 to 1954. She was less than a year old when she came to Alaska and doesn't remember much of her time on the island. But when the family came back for a visit in 2005, she started collecting her parent's recollections and decided to put them into a book. In 1901, Congress appropriated $100,000 for eleven lighthouses along the Alaska coast. Guard Island was built in 1903-1904. By the 1920s, the original wooden buildings had deteriorated and were replaced with reinforced concrete ones in 1922. The original lighthouse keepers were civilian employees of the government but, in 1939, the Coast Guard took over Guard Island operations. "My dad was transferred to Guard Island for a year in January, 1951," Waugh writes. "They called it 'isolated duty' because the conditions resulted in confinement and because he served long periods of continuous duty." Dan Moore was the engineer on the island. There were other Coast Guard personnel there as well the Milton Fox and his family. After Fox transferred to Ketchikan, the lighthouse head, Chief Sydney Jackson, suggested that Moore bring his family to join him. "There were several things to consider," Waugh writes. "Daddy's duty was not over yet and mother and I could only be with him by moving up there (from Vancouver, Washington). They'd be able to save some money because he received isolated duty pay and because most expenses were covered. On the flip side, there was the isolation. Plus they would have a new baby - me. All the factors were weighed, and the decision was made to move the family to Guard Island." The family came up on the SS Denali. "It was a 50 passenger steam liner and it was a luxury cruise ship in its day," Waugh writes. "During the two-day trip, we were treated like royalty. We had a nice stateroom and the gourmet meals were served in a formal dining room. Very soon, though, we'd be going from royalty to reality." Waugh writes that the family brought all their worldly goods in two 75-pound steamer trunks. They also brought their dog, Salty. There was no dock on Guard Island so they had to transfer to two 15-foot skiffs from the larger boat they arrived on. The skiffs were launched from the island boathouse down a ramp with a small trolley car. When the car reached water, the skiffs would float free. When the skiff came back to the island, it would slide onto the trolley cradle and then be winched back up to the boathouse. There were two residences on the larger of the two islands. The house the family lived in was a relatively spacious, three story white Cape Cod style house with dormers and fancy curlicues on the eaves. "We were self sufficient on the island," Waugh writes. "Rainwater and melted snow were collected on the roofs and drained into concrete sisterns. Our drinking water was purified with bleach. Oil was delivered to the island in a tank on a barge from Ketchikan. Sewage went right out into the ocean via pipes. Most of our garbage was simply flung off the back stoop into the water. It was an easy toss since the ground dropped sharply down from there. What didn't make it into the sea was quickly picked up by seagulls." The lighthouse crew was in hourly radio contact with authorities in Juneau and also frequently radioed the Coast Guard in Ketchikan, mostly to talk about supplies. Waugh writes that Thursday was the big day each week because that was the day the mail and supply boat arrived at Guard Island. Waugh's mother, Alline, frequently spent most of the day Wednesday writing lengthy letters to her relatives and friends. The basement of the house the family lived in was a large pantry they called the "commissary." It had to be well stocked because it wasn't unusual for the supply boat to skip a visit because of the weather. Part of Alline's island duties was to cook at least one meal a day for the crew and Waugh writes that "a talent for cooking had to be cultivated on the island. As Mother said 'boy, was I cultivated.'" "Surprisingly, fresh fish wasn't eaten much for two reasons," Waugh writes. "First, the crew worked so much they had little time to fish. Second, none of them knew how to catch salmon, and they thought everything else was garbage." Prior to the family's arrival, Waugh writes, the crew had had to cook for themselves for nearly six months. Waugh says they very happy when Alline arrived because they had become very adept at making "seagull food" or recipe mistakes that had to be thrown out. "To make things homier for the seamen, Mother asked them each to write to their mothers, asking for their favorite recipes," Waugh writes. "Of course, the mothers were thrilled to accommodate the requests."

Waugh collected those recipes and published them in her book. Besides the lighthouse guiding mariners into Tongass Narrows, the main function of the Guard Island station was the radio beacon transmitter signal. Boats, ships and airplanes used the beacon to help triangulate their positions and the crew had to maintain the signal watch 24 hours a day. Dan Moore's shift was from 6 am to 6 pm every day. The crew also radioed hourly weather reports to the Juneau office. The lighthouse beacon was turned on everyday an hour before sundown and turned off an hour after sunup. The light on the 34-foot tower was visible for 17 nautical miles. Of the course the station also operated during the frequent fogs. The foghorn could be heard five miles away, Waugh writes. And unfortunately it was aimed right at her bedroom window, some 75 feet away. "The adults learned to talk in 25-second intervals, and automatically suspend their conversations for five seconds in time with the noise, since they couldn't hear anything over it anyway," Waugh writes. "Of course, we're all hard of hearing these days!" Even though Ketchikan was barely 12 miles away, the family never visited it. "Mother never left the island the twenty months we were there," Waugh writes. "Daddy did, but only a few times. Once he putted around the island in the motor boat to take movies. And once, he got to go way over to Point Higgins which was three miles away to pick up a special order." The family's main form of entertainment was reading, Waugh writes. Her father's Hallicrafter radio could also occasionally pick up radio programs from the Lower 48. "Gunsmoke" was a particular favorite. "The static from the radio beacon always interrupted the reception for five seconds twice a minute," Waugh writes. "My parents remember several times they'd be listening to a suspenseful program and somebody got shot, but they missed who it was." Waugh writes that she had a generally normal childhood, even though the island was not a normal place to grow up. She got her first teeth, learned how to walk and was potty trained in the narrow confines of the island. Because staying on the island was helping the family financially, they agreed to stay on several months past their original one year agreement. They invested the money they were saving in government bonds and had more than $5,000 when they left. That money eventually allowed them to buy a car and house trailer. Finally, after nearly two years, they left the island for Ketchikan and then flew back to Seattle. In August 2005, the family returned to Ketchikan on a cruise ship. They rented a skiff at Clover Pass and went back to Guard Island. "As we had heard the place was in ruins," Waugh writes. "Piles of concrete was all that remained of the buildings. In many ways, the memories were better than the reality. For my parents, especially Daddy, seeing the change was painful." Back in Ketchikan, the family talked about the visit and agreed they were glad they had come back "That afternoon, after we sailed out of Ketchikan and headed north, we passed close by Guard Island," Waugh writes. "We all had a drink as we sat in the lounge on the 12th deck and enjoyed a great perspective on the tiny rock with a lighthouse perched on it. It was raining again, cold and windy. Even so, I went outside to get a better look, and take more photographs. I felt warm despite the weather."

Editor's note: Chris Waugh will be presenting a slide and video show of her family's time on Guard Island at The Southeast Alaska Discovery Center 7 pm Friday, September 22. Waugh will also be signing books at Parnassus Books on Wednesday, September 20, 2006.

Dave Kiffer is a freelance writer living in Ketchikan, Alaska. Contact Dave at dave@sitnews.us Publish A Letter on SitNews Read Letters/Opinions

|

|||