Wrangell keeps fishing base through decades of changeBy CONOR BELL

September 10, 2014

The Russian American Company built a fort by the Stikine River in 1834, which it began leasing to the British Hudson Bay Company six years later. The British company continued the fur trade until 1849, when it abandoned the fort due to a poor relationship with the Tlingits.

Float houses rest on the mud in Wrangell.

Traffic through the town slowed as other routes proved easier, but a base of businesses was already in place, allowing other industries to develop. A history of timber The fishing and logging industries gained prominence in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. While fishing’s presence in Wrangell’s economy has been steady, logging grew continuously through the 20th century. Initially supplying wood for local construction and crates for shipping salmon, the local sawmill provided lumber for airplane manufacturing beginning around 1920. It also produced wood for U.S. military bases through World War II and for Japanese industries through most of the second half of the century. Total employment in Wrangell fluctuated between 900 and 1,100 through the 1980s and early 1990s, with logging by far the largest employer. The Tongass Timber Reform Act of 1990 limited harvesting areas and ended heavy federal subsidization. The Wrangell sawmill, which had been the town’s primary economic driver, closed in 1995. Just one year prior, the sawmill alone had provided almost 20 percent of the area’s employment and 30 percent of wages. Between 1994 and 1997, the population decreased from 2,800 to 2,500, and in 2006, it bottomed out at 2,200 0 20 percent lower than in 1994. Since then, the city’s population and jobs have never fully rebounded.

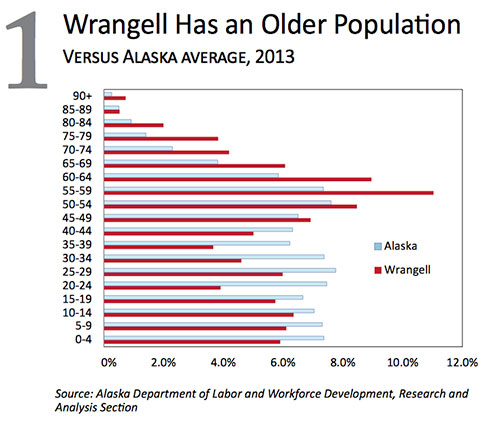

Older, less diverse population Today, the City and Borough of Wrangell’s population is around 2,500, with mild losses projected over the next few decades. The population is older, with a median age of 47 (see Exhibit 1) — considerably higher than Alaska’s 34 years and the United States’ 37. Older population have lower birth rates and more deaths, and Wrangell also tends to lose population through more people moving out than in, which is common for smaller Alaska communities. Wrangell's composition also differs from the state as a whole in that is is 73 percent white versus 67 percent for Alaska. While Wrangell has a much smaller percentage of blacks, Asians, and Hispanics than Alaska, it has a slightly larger share of Alaska Natives. Lower wages and income Wrangell's average annual wages and average personal income are both lower than statewide. In 2013, Wrangell's average yearly wage - which doesn't include earning from fishing - was $37,520, and Alaska's was $51,030. Per capita personal income, which encompasses wages plus all other sources of income including fishing was $39,359 in 2012 (For personal income, 2012 data are the most recent available.), considerably below the statewide average of $49,436. Personal income includes transfer payments - such as retirement income, dividends, and welfare - and Wrangell has more per capita, mainly due to its older population. However, this additional income doesn't fully compensate for the city's lower wages.

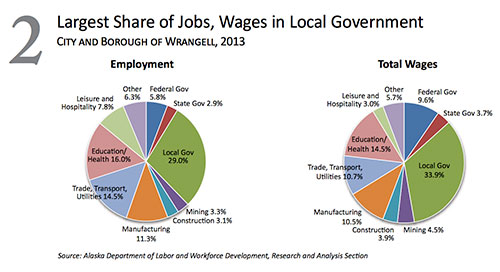

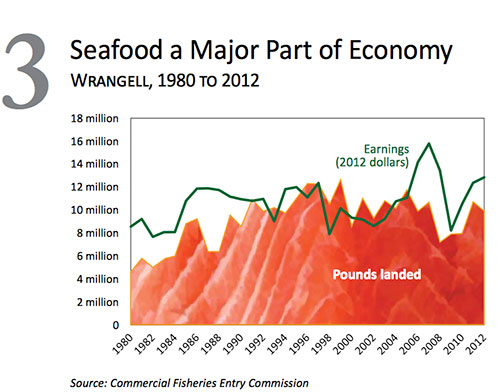

Wrangell's employment is 38 percent government (see Exhibit 2), and as is common in small communities, it's largely local. Local government represents 29 percent of all jobs in Wrangell and includes the school district and the Wrangell Medical Center. Local government jobs, which provide basic services in small communities, tend to pay less than state and federal jobs. Heavy reliance on government jobs also suggests a lack of other economic activity. Federal employment makes up a much smaller share, at 6 percent, and is mainly U.S. Forest Service. State jobs are scarce at just under 3 percent of total employment compared to 8 percent for Alaska as a whole, and include a handful of jobs at the Department of Fish and Game and the Department of Transportation of Public Facilities. Fishing plays a major role Fish harvesting is a key piece of Wrangell's economy, but these workers don't show up in regular employment data because they're generally considered self-employed. Because the employment figures in the rest of this article exclude fish harvesting, alternative measures are necessary to quantify its role in the economy. Wrangell residents fished 259 permits in 2012. These residents brought in 9.9 million pounds that year and 12.9 million in earnings (see Exhibit 3), with 57 percent coming from salmon permits. For a permit holder, this averages out to $77,895 in gross earnings. While fisheries earnings vary from year to year, 2012's earnings were near the 10-year average of $11.8 million.

Seafood processing is highly seasonal and spikes with the summer salmon season. Manufacturing jobs peaked at 237 in August of that year. Wrangell also draws in fishermen from the surrounding area with its marine service center, which has a 300-ton boat lift. Fewer cruise ships While Wrangell doesn't have Juneau's or Ketchikan's high volume of visitors it brings in a steady flow of travelers throughout the summer - about 18,000 in the summer of 2011. For comparison, Juneau had 917,000 and Ketchikan brought in 867,000 that season. Wrangell is scheduled to receive more than 50 cruise ships this summer, mainly small ones. The community lacks the larger cities' ability to port ships carrying thousands of passengers; its largest visiting ship carries about 500. Just four ships that visit Wrangell carry more than 100 passengers, and these make 10 total summer visits. Visitor-related industries average 73 monthly jobs in 2013, fluctuating from 54 in February to 89 in July. Wrangell has several notable visitor attractions. It's home to the Petroglyph Beach State Historic Part, which has the highest concentration of rock engravings in Southeast Alaska. George T. Emmons, an ethnographer, wrote in the early 20th century that no Tlingit elders knew of the engravings' origin, and some denied they were created by Tlingit ancestors. There's no consensus on their age, either, but some speculate they could be thousands of years old. Other destinations include the Anan Wildlife Observatory, 30 miles from town by charter boat or float plane, and Anan Creek, which has one of Southeast's largest pink salmon runs as well as a large population of grizzly and black bears.

Conner Bell, an Alaska Department of Labor economist in Juneau, specializes in the employment and wages of the Southeast and Southwest economic regions. E-mail Conor. Bell@alaska.gov Material in Alaska Economic Trends is public information, and with appropriate credit may be reproduced without permission. Alaska Economic Trends is provide by the Alaska Department of Labor and Workforce Development.

|

||