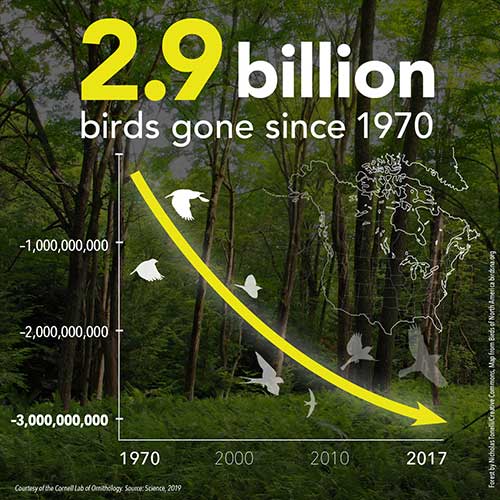

New study finds US and Canada have lost more than 1 in 4 birds in the past 50 years

September 20, 2019

"Multiple, independent lines of evidence show a massive reduction in the abundance of birds," said Ken Rosenberg, the study's lead author and a senior scientist at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology and American Bird Conservancy. "We expected to see continuing declines of threatened species. But for the first time, the results also showed pervasive losses among common birds across all habitats, including backyard birds."

The study notes that birds are indicators of environmental health, signaling that natural systems across the U.S. and Canada are now being so severely impacted by human activities that they no longer support the same robust wildlife populations. The findings showed that of nearly 3 billion birds lost, 90 percent belong to 12 bird families, including sparrows, warblers, finches, and swallows -- common, widespread species that play influential roles in food webs and ecosystem functioning, from seed dispersal to pest control. Among the steep declines noted:

"These data are consistent with what we're seeing elsewhere with other taxa showing massive declines, including insects and amphibians," said coauthor Peter Marra, senior scientist emeritus and former head of the Smithsonian Migratory Bird Center and now director of the Georgetown Environment Initiative at Georgetown University. "It's imperative to address immediate and ongoing threats, both because the domino effects can lead to the decay of ecosystems that humans depend on for our own health and livelihoods -- and because people all over the world cherish birds in their own right. Can you imagine a world without birdsong?" Evidence for the declines emerged from detection of migratory birds in the air from 143 NEXRAD weather radar stations across the continent in a period spanning over 10 years, as well as from nearly 50 years of data collected through multiple monitoring efforts on the ground. "Citizen-science participants contributed critical scientific data to show the international scale of losses of birds," said coauthor John Sauer of the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS). "Our results also provide insights into actions we can take to reverse the declines." The analysis included citizen-science data from the North American Breeding Bird Survey coordinated by the USGS and the Canadian Wildlife Service -- the main sources of long-term, large-scale population data for North American birds --the Audubon Christmas Bird Count, and Manomet's International Shorebird Survey. Although the study did not analyze the causes of declines, it noted that the steep drop in North American birds parallels the losses of birds elsewhere in the world, suggesting multiple interacting causes that reduce breeding success and increase mortality. It noted that the largest factor driving these declines is likely the widespread loss and degradation of habitat, especially due to agricultural intensification and urbanization. Other studies have documented mortality from predation by free-roaming domestic cats; collisions with glass, buildings, and other structures; and pervasive use of pesticides associated with widespread declines in insects, an essential food source for birds. Climate change is expected to compound these challenges by altering habitats and threatening plant communities that birds need to survive. More research is needed to pinpoint primary causes for declines in individual species. "The story is not over," said coauthor Michael Parr, president of American Bird Conservancy. "There are so many ways to help save birds. Some require policy decisions such as strengthening the Migratory Bird Treaty Act. We can also work to ban harmful pesticides and properly fund effective bird conservation programs. Each of us can make a difference with everyday actions that together can save the lives of millions of birds -- actions like making windows safer for birds, keeping cats indoors, and protecting habitat."

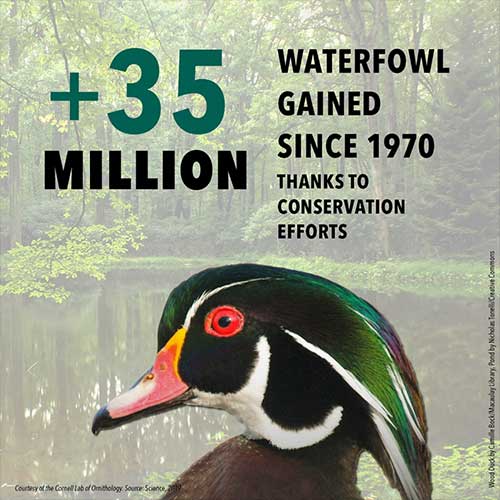

The study also documents a few bright spots for birds. Among the population models, raptor populations – hawks, eagles and other birds of prey – have tripled since 1970. The study’s authors said that uptick is attributable to government regulations that banned the harmful pesticide DDT and made shooting raptors illegal. Waterfowl populations have grown 50% in the past 50 years. The scientists said that’s due to dedicated programs such as the North American Waterfowl Management Plan and its billions of dollars invested into wetlands conservation and international collaboration, as well as the establishment of a federal no-net-loss wetlands policy. Rosenberg, a faculty fellow at the Atkinson Center for a Sustainable Future, said the success in wetlands conservation for waterfowl may provide a blueprint for turning around the steep declines among grassland birds. Even if 30% of North America’s birds are lost, there are still 70% left to spur a recovery if conservation measures can be implemented. But conservation action must come soon, he said. “I don’t think any of these really major declines are hopeless at this point,” Rosenberg said. “But that may not be true 10 years from now.” "It's a wake-up call that we've lost more than a quarter of our birds in the U.S. and Canada," said coauthor Adam Smith from Environment and Climate Change Canada. "But the crisis reaches far beyond our individual borders. Many of the birds that breed in Canadian backyards migrate through or spend the winter in the U.S. and places farther south -- from Mexico and the Caribbean to Central and South America. What our birds need now is an historic, hemispheric effort that unites people and organizations with one common goal: bringing our birds back."

On the Web:

Edited by Mary Kauffman, SitNews Source of News:

|

|||||