Analysis Trump, Ukraine and a whistleblower: Ever since 1796, Congress has struggled to keep presidents in checkBy JENNIFER SELIN

September 25, 2019

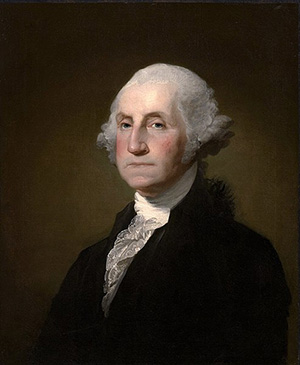

Washington thought that giving the House papers respecting a negotiation with a foreign power would be to establish a dangerous precedent.

Washington’s reluctance to hand over these documents has echoed through time, in conflicts between Congress and Presidents Monroe, Jefferson, Adams all the way to Presidents Coolidge, Kennedy, Nixon and Reagan, among others. For the most part, members of Congress still must rely on the president and his administration for information in the areas of foreign relations and intelligence. In the latest version of that long-running tension between Congress and the president over power, Acting Director of National Intelligence Joseph Maguire is scheduled to testify on Sept. 26 before the House Intelligence Committee. The testimony is part of a chain of events that began in mid-August of 2019 when an anonymous whistleblower filed a complaint with the inspector general for the intelligence community, who is tasked by Congress to identify problems in the national intelligence agencies. The complaint related to reports that President Trump pressured Ukraine to investigate former Vice President Joe Biden and his family. The developing conflict between Trump and Congress has involved, among other aspects, a struggle over who can have access to crucial documents. The Intelligence Committee will no doubt use Maguire’s testimony as a preliminary step in the formal impeachment inquiry announced by House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, a Democrat, on Tuesday. Questions about the degree to which the legislative and executive branches of the U.S. government should share power have arisen throughout the nation’s history. While a simple view of the American Constitution revolves around the idea that the federal government is divided into three coequal branches, this understanding is incomplete. The Founders struggled with problems related to the separation of powers. The text of the Constitution, combined with subsequent legal analysis, shows tension between a desire to separate the branches and the need to integrate the federal government’s core functions. Foreign relations and national security issues like those underlying the Ukraine conflict only exacerbate this tension. President’s broad authorityPelosi’s announcement relied heavily on references to the U.S. Constitution. At one point, she said, “Our republic endures because of the wisdom of our Constitution enshrined in three coequal branches of government serving as checks and balances on each other.” Yet, what exactly does the Constitution say about the relationship among these three branches? Over time, the Constitution’s language has been interpreted to grant the president broad authority in the conduct of foreign affairs. Many recognize presidential power is greatest when the president directs foreign policy. The president’s broad power is partly by design. Imagine if the president had to publicly broadcast his strategy and build a legislative coalition every single time he communicated with a foreign leader. And part of the president’s power is a result of the accumulation of laws granting policy authority to the executive branch over time. Regardless, there is no question that the Founders intended for members of Congress to exercise oversight of presidential conduct in foreign policy. In fact, Congress first established a congressional committee to request executive branch documents relating to foreign relations in 1792. Yet then, as now, lawmakers struggled to obtain the requested information. Oversight system’s weaknessesBecause voters in contemporary politics reward or punish the president for issues that arise in foreign relations, presidents have a reason to control the narrative when it comes to national security. Congress often has little incentive – or ability – to do much about it. There is waning congressional interest in oversight of foreign policy. Reelection concerns encourage members of Congress to focus their energies on domestic affairs and constituent service. When legislators do get involved in foreign policy, they are often in a reactive position. Because of the president’s constitutional freedom to initiate contact with foreign powers, the president has an advantage over Congress. Furthermore, the nature of the oversight system can hinder legislators’ responses to presidential action. It takes time and resources to coordinate a response, not to mention agreement among a majority of members of Congress. What’s old is new againSo what makes the crisis involving Trump, Ukraine and the whistleblower different from other foreign policy power struggles between Congress and the executive branch? Perhaps this is a Trump issue, not a foreign policy issue. More constituents are pressuring their Democratic congressmen to pursue impeachment than ever before. This straightforward conflict may provide a clear story for Democrats to tell. Yet, despite providing a written record of the call between Trump and Ukraine’s leader, the president and his administration still control much of the information about the events. And Congress has limited time and resources to force the executive branch to relinquish this information, particularly if Congress wishes to do so before the 2020 election. While Congress can appeal to the courts to compel disclosure of documents it needs in its investigation of the Ukraine affair, it is unclear whether the courts would do so. Separation of powers issues and what is called the political question doctrine – which says some disputes are too political in nature for the judiciary – makes courts reluctant to interfere in political fights between Congress and the president, particularly about national security. The situation is further complicated by the fact that Republican support for Trump appears intact, making coordination across the chambers of Congress quite difficult. While the current battle between Trump and congressional Democrats is newsworthy, it is not entirely new. The fight for information over the president’s negotiations with foreign powers is an inevitable consequence of the U.S. constitutional system.

|

|||||