Dozens of Dinosaur Footprints Reveal Ancient Ecosystem of Alaskan Peninsula

October 30, 2019

Fiorillo has done extensive research in Alaska during the past two decades, he will never forget his first visit to Aniakchak National Monument and Preserve, one of the least-visited places in the National Park System (NPS). Located in the region around the Aniakchak volcano on the Aleutian Range, this 601,294-acre monument is one of the least-visited places in the National Park System due to its remote location and difficult weather.

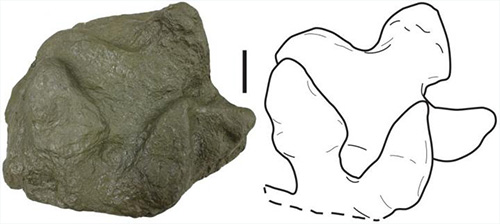

Now, 18 years later, research conducted by the veteran paleontologist has been published in one of the world’s most prestigious science journals, PLOS ONE. The paper documents Fiorillo’s findings of a diverse assemblage of fossils – including birds, plants and many dinosaurs – representing life some 70 million years ago in Aniakchak. Fiorillo’s studies show that southern Alaska was home to a variety of creatures, and among those were herds of hadrosaurs (duck-billed dinosaurs) that cared for their young. The hadrosaurs – that he fondly dubs as “the caribou of the Cretaceous” – were found often in the ancient environments believed to be humid and coastal. “Our study shows that despite how remote Aniakchak National Monument is today for visitors, it was home to an abundance of dinosaurs – a virtual paleontological candy store for dinosaur studies,” said Fiorillo. “Also, we found many fossil tracks along the ancient bay and river deposits preserved in these rocks, demonstrating that even dinosaurs enjoyed a day at the beach.” One of the co-authors on this new study, Dr. Yoshitsugu Kobayashi (Hokkaido University Museum, Sapporo, Japan) adds, “This study provides us a better understanding of the high-latitude dinosaur ecosystems of Alaska. Such an understanding will help us address important questions such as did dinosaurs survive the winters there and, if so, how did they survive? Similarly, how did the dinosaurs migrate between North America and Asia during the Cretaceous?” Fiorillo’s journey began in 2001 when he partnered with the National Park Service, Alaska Region, in search of dinosaur remains on the Alaska Peninsula. The locale was remote and difficult to reach, requiring the service of a float plane and a whitewater raft to circumvent the Aniakchak River. After days of unfruitful exploration, a sense of melancholy took over as they neared the end of the river. Time was nearing to break down the rafts and head back to King Salmon. As often is the case in a paleontological field project, in the final hours of the trip Fiorillo peered around the last corner, and his eye caught the image of a 70 million-year-old, three-toed impression of a duck-billed dinosaur. “Not only was it the first record of a dinosaur in this remote national park unit, but it was the first record of a dinosaur in the entire Alaska National Park system,” said Fiorillo. He returned to Aniakchak the following year to thoroughly document this track, but the prohibitive travel costs were a challenge, deterring his further research efforts. From 2003-2015, he partnered again with the National Park Service and headed to Denali National Park, just a few hours from Fairbanks. In Denali, Fiorillo and an international team of scientists discovered and documented several new species and thousands of tracks attributable to a variety of dinosaurs and other fossil animals. Satisfied with his work in Denali, Fiorillo chose to make a return visit to Aniakchak – this time with a more attuned eye for footprints. Since 2016 and every summer since, he and his team have continued their survey, all while fighting mosquitos, bears, weather and other elements. “We documented dozens and dozens of footprints, which I clearly missed in my earlier work. And this time, we found an abundance of duck-billed dinosaur footprints representing both adults and juveniles,” said Fiorillo. “But we also found much greater biodiversity with tracks attributable to fossil birds, a meat-eating dinosaur about the size of the pygmy tyrannosaur we unearthed in Arctic Alaska, armored dinosaurs, and fishes.” The trackways in the Aniakchak National Monument were preserved in the Chignik Formation, a series of coastal sediment deposits dating back to the Late Cretaceous Period around 66 million years ago. Survey work from 2001-2002 and 2016-2018 identified more than 75 trackway sites including dozens of dinosaur footprints. Based on the anatomy of the prints, the authors identified two footprints of armored dinosaurs, one of a large predatory tyrannosaur, and a few footprints attributable to two types of birds. The remaining 93% of the trackways belonged to hadrosaurs, highly successful herbivores which are typically the most common dinosaurs in high-latitude fossil ecosystems. Previous research on skeletal dinosaur remains in northern Alaska has found that hadrosaurs were most abundant in coastal habitats. The trackways documented in this study reveal that the same trend was true in southern Alaska. The authors suggest that understanding habitat preferences in these animals will contribute to understanding of how ecosystems changed through time as environmental conditions shifted and dinosaurs migrated across northern corridors between continents. Fiorillo adds, "Our study shows us something about habitat preferences for some dinosaurs and also that duck-billed dinosaurs were incredibly abundant. Duck-billed dinosaurs were as commonplace as cows, though given we are working in Alaska, perhaps it is better to consider them the caribou of the Cretaceous."

On the Web:

Funding:

Edited by Mary Kauffman, SitNews

Source of News:

|

||||