Discovery Of Alaska Spear Points Raises New Questions About Human Arrival In North America

November 09, 2013

In a new scientific paper co-written by members of a team of researchers associated with the Center for the Study of the First Americans (CSFA) at Texas A&M University, they note that two contentious issues are the timing of colonization of the Bering Land Bridge and origin of Clovis, which at 13,000 calendar years ago is the earliest unequivocal complex of archaeological sites in temperate North America, known by its specialized fluted spear points. The 2005 discovery of fluted spear points in northwest Alaska strongly suggests that early humans carrying American technology lived on the central Bering Land Bridge about 12,000 years ago, showing that peopling of the Americas was more complex than previously believed.

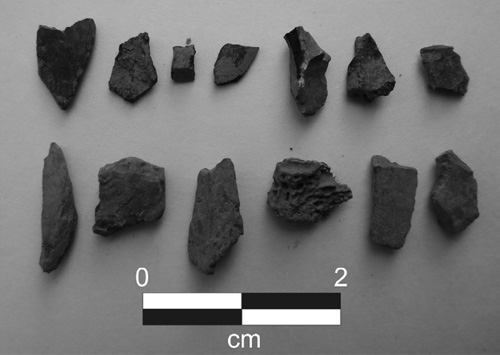

Carbonized bone fragments from Serpentine fluted-point site excavations

One hypothesis holds that spear point fluting technology emerged in Beringia, and then was carried southward, with fluted points becoming the diagnostic “calling card” of early Paleoindians spreading across the Western Hemisphere. Fluted points have long been known from Alaska, yet until now they have never been found in a datable geologic context, making their relationship to Clovis a mystery. In the new paper, the researchers show that a new archaeological site at Serpentine Hot Springs in Alaska’s Bering Land Bridge National Preserve, contains fluted points in a stratified geologic deposit dating to no earlier than 12,400 calendar years ago, and that these results suggest that Alaska’s fluted-point complex is too young to be ancestral to Clovis, and that it instead represents either a south-to-north dispersal of early Americans or transmission of fluting technology from temperate North America, which in turn suggests that peopling of the Americas and development of Paleoindian technology were much more complex than traditional models predict. The researchers focused on the Serpentine Hot Springs site, now part of the Bering Land Bridge National Preserve, located on the Seward Peninsula, where in 2005 park archaeologists discovered a fragment of a fluted spear point, an artifact long associated with North American Paleoindian cultures. Dr. Goebel and the team later excavated the site, finding more fluted points. “This shows for sure that there were humans on the land bridge by the end of the Ice Age, 12,000 years ago, because the spear points were found with charcoal and bone radiocarbon dated to that time,” Dr. Goebel explains in a TAMU Times release. “Several of the spear points were found in our excavation along with charred animal bones, probably caribou which ancient humans butchered and ate there at the site. So the question becomes, ‘Who were these people , and where did they come from?’” Dr. Goebel says that among the earliest residents of North America were members of the Clovis culture, thought to date to about 13,000 years ago. Clovis people specifically fashioned their stone spear tips with grooved, or fluted, bases. Such human-made projectile points have been known in Alaska since 1947, having been found at as many as 20 different archaeological sites, noting: “But no one has been able to determine the age of fluted points in Alaska — were they younger, the same age as, or older than the Clovis residents in temperate North America?” “The evidence from Serpentine supports the second theory – that either Paleoindian people or technologies were moving in a reverse migration pattern, from south to north, or more specifically, from the high plains of central Canada in a northerly direction into Alaska,” says Dr. Goebel, adding that the recent findings show new possibilities about when and from where the early settlers of the Bering land bridge arrived. “Not all of Beringia’s early residents may have come from Siberia, as we have traditionally thought,” he notes. “Some may have come from America instead, although millennia after the initial migration across the land bridge from Asia. If the fluted points do not represent a human migration, they at least indicate the surprisingly early spread of an American technology into Arctic Alaska.” He adds that the fluted points were used by the Serpentine residents as weapon tips for hunting large animals, such as caribou or bison, and that the bow and arrow would not appear in Alaska for several thousand more years. “We know these early settlers were very mobile – they traveled great distances,” Dr. Goebel continues. “Humans carried tools made of the volcanic glass called obsidian to the site from nearly 300 miles inland in central Alaska. The artifacts and other debris they left behind suggests very short stays, perhaps just several days and nights. Nonetheless, fluted points have yet to be found in neighboring Chukotka (in Russia) suggesting that the fluted-point makers never made it any further west than the Seward Peninsula. By 12,000 years ago, the land bridge was becoming swamped by the rising Bering and Chukchi seas.” The JAS paper, entitled “Serpentine Hot Springs, Alaska: results of excavations and implications for the age and significance of northern fluted points,” is co-authored by Ted Goebel, Heather L. Smith, Michael R. Waters, and Kelly E. Graf of TAMU; Lyndsay DiPietro and Steven G. Driese of Baylor University at Waco; Bryan Hockett of U.S.D.I. Bureau of Land Management; Robert Gal of Alaska Region, National Park Service; Sergei B. Slobodin of the Northeast Interdisciplinary Science Research Institute, Far Eastern Branch, Russian Academy of Sciences, at Magadan, Russia; Robert J. Speakman of the Center for Applied Isotope Studies, University of Georgia at Athens, GA, and David Rhode of the Desert Research Institute at Reno, NV.

Sources of News:

E-mail your news &

photos to editor@sitnews.us

|

||