Fukushima Radioactivity Detected Off Pacific Coast; Judged Harmless

November 19, 2014

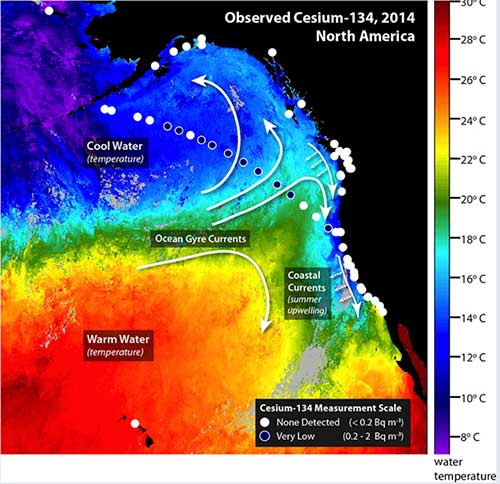

In the aftermath of the 2011 tsunami off Japan, the Fukushima Dai-ichi Nuclear Power Plant released cesium-134 and other radioactive elements into the ocean at unprecedented levels. Since then, the radioactive plume has traveled east across the Pacific, propelled largely by ocean currents and being diluted along the way. At their highest near the damaged nuclear power plant in 2011, radioactivity levels peaked at more than 10 million times the levels recently detected near North America. "We detected cesium-134, a contaminant from Fukushima, off the northern California coast. The levels are only detectable by sophisticated equipment able to discern minute quantities of radioactivity," said Ken Buesseler, a WHOI marine chemist, who is leading the monitoring effort. "Most people don't realize that there was already cesium in Pacific waters prior to Fukushima, but only the cesium-137 isotope. Cesium-137 undergoes radioactive decay with a 30-year half-life and was introduced to the environment during atmospheric weapons testing in the 1950s and '60s. Along with cesium-137, we detected cesium-134 – which also does not occur naturally in the environment and has a half-life of just two years. Therefore the only source of this cesium-134 in the Pacific today is from Fukushima." The amount of cesium-134 reported in these new offshore data is less than 2 Becquerels per cubic meter (the number of decay events per second per 260 gallons of water). This Fukushima-derived cesium is far below where one might expect any measurable risk to human health or marine life, according to international health agencies. And it is more than 1000 times lower than acceptable limits in drinking water set by US EPA. Scientists have used models to predict when and how much cesium-134 from Fukushima would appear off shore of Alaska and the coast of Canada. They forecast that detectable amounts will move south along the coast of North America and eventually back towards Hawaii, but models differ greatly on when and how much would be found. "We don't know exactly when the Fukushima isotopes will be detectable closer to shore because the mixing of offshore surface waters and coastal waters is hard to predict. Mixing is hindered by coastal currents and near-shore upwelling of colder deep water," said Buesseler. "We stand to learn more from samples taken this winter when there is generally less upwelling, and exchange between coastal and offshore waters maybe enhanced." Because no U.S. federal agency is currently funding monitoring of ocean radioactivity in coastal waters, Buesseler launched a crowd-funded, citizen-science program to engage the public in gathering samples and to provide up-to-date scientific data on the levels of cesium isotopes along the west coast of North America and Hawaii. Since January 2014, when Buesseler launched the program, individuals and groups have collected more than 50 seawater samples and raised funds to have them analyzed. The results of samples collected from Alaska to San Diego and on the North Shore of Hawaii are posted on the website http://OurRadioactiveOcean.org. To date, all of the coastal samples tested in Buesseler's lab have shown no sign of cesium-134 from Fukushima (all are less than their detection limit of 0.2 Becquerel per cubic meter). The offshore radioactivity reported this month came from water samples collected and sent to Buesseler’s lab for analysis in August by a group of volunteers on the research vessel Point Sur sailing between Dutch Harbor, Alaska, and Eureka, California. Click on the map for a larger view. These results confirm prior data described at a scientific meeting in Honolulu in Feb. 2014 by John Smith, a scientist at Fisheries and Oceans Canada in Dartmouth, Nova Scotia, who found similar levels on earlier research cruises off shore of Canada. Buesseler and Smith are now working together on a new project, led by Jay Cullen at the University of Victoria, Canada, called InFORM that involves Canadian academic, government and NGO partners to determine and communicate the environmental risks posed by Fukushima for Canada’s Pacific and Arctic coasts and their inhabitants. Buesseler believes the spread of radioactivity across the Pacific is an evolving situation that demands careful, consistent monitoring of the sort conducted from the Point Sur. "Crowd-sourced funding continues to be an important way to engage the public and reveal what is going on near the coast. But ocean scientists need to do more work offshore to understand how ocean currents will be transporting cesium on shore. The models predict cesium levels to increase over the next two to three years, but do a poor job describing how much more dilution will take place and where those waters will reach the shore line first," said Buesseler. "So we need both citizen scientists to keep up the coastal monitoring network, but also research vessels and comprehensive studies offshore like this one, that are too expensive for the average citizen to support," said Buesseler. Buesseler presented his results on Nov. 13, 2014, at the SETAC conference in Vancouver. Ken Buesseler is a senior scientist at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) who specializes in the study of natural and man-made radionuclides in the ocean. Buesseler's work includes studies of fallout from atmospheric nuclear weapons testing, assessments of Chernobyl impacts on the Black Sea, and examination of radionuclide contaminants in the Pacific resulting from the Fukushima nuclear power plants.

Edited by Mary Kauffman, SitNews

Editor's Note:

|

|||