An Alaska Journey: From WWII Ketchikan To The 1964 Anchorage Good Friday EarthquakeBy ARNE L. BUE April 11, 2014

Generally, the siren sounded around 6 PM. My Father, Mother, siblings and I left our dinner table and marched out the back door. With our neighbors we climbed a rocky portion of trail and trekked single file into the woods to a small air raid shelter.

A Royal Canadian Hawker Hurricane

At night, my parents pulled the curtains and window shades. When I peeked out, Ketchikan was dark. My parents told me not to peek like that. It was a time of blackout along the western shores of the United States from Alaska to San Diego, including Ketchikan. Blackout curtains or window shades were required after dark. The late Ted Ferry once told of building a blackout entrance to Ferry's food store on the curve of Water-Tongass Avenue, so that customers could come into and out of the store after dark without leaking any light. (June Allen, "Sit News: Stories in the News, Ketchikan, Alaska," (Source: The Forgotten War: June 03, 1942-August 1943, June 03, 2002, http://www.sitnews.org/JuneAllen/060302_forgotten_war.html) My uncles, Harry and Ture Larsen, served in the Aleutians and the Pacific Theater, respectively, Harry in the Army, Ture in the Navy. My hand-me-downs came from my older brother: shirts, pants, and knickers.

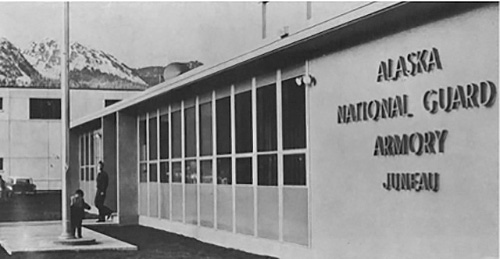

Arne L. Bue, knickers More than once I asked my Mother when I could get regular pants. "After the war is over," she said. There were no nylons for women, other shortages. My Mother darned socks, patched my brother's pants and my knickers. The clothing never seemed to wear out because of her. The knickers would not go away. I wanted the war to end. Ketchikan had friends who defended against the Japanese: The Royal Canadian Air Force. We kids reverently called them "our Allies." We really liked them. Canada's Western Air Command band even paraded through Ketchikan in 1943. (Source: Brendan Coyle, War on our Doorstep: The Unknown Campaign on North America's West Coast, (Heritage House, 2002), 60) Canada became the first and only Allied power to set up a military base on United States soil and the only foreign nation to directly assume defence [sic] of American territory. (Source: Brendan Coyle, War on our Doorstep: The Unknown Campaign on North America's West Coast, (Heritage House, 2002), 51-52) By 1942 a ground crew and a Canadian Army unit, the 286th Artillery, was on Annette Island where they set up operations. Over time these operations included P-40 Kittyhawks, Hawker Hurricanes, Lockheed Ventura Bombers as well as twin engine "Boleys" which the RCAF fitted with racks of forward-firing, .303-calibre, armor- piercing machine guns and reconnaissance cameras for vessel identification. (Source: Brendan Coyle, War on our Doorstep: The Unknown Campaign on North America's West Coast, (Heritage House, 2002) Finally, one day... Church bells rang. Shop owners left their places of business and ran into the streets. Within 10 minutes after the President's announcement, the Chronicle was on the streets with an extra, first as usual. (Source: "Truman Accepts Japanese Surrender," Ketchikan Alaska Chronicle, August 14, 1945, front page.) "The war is over," my Mother said. Now, I'd get my own long pants! In1957, Ketchikan High School gave me a diploma; and after earning money aboard a seiner out of Metlakatla as a crewman I attended Pacific Lutheran College. For three ensuing summers I worked with Uncle Ture on his commercial fishing boat the "Sandra Lynn" to pay for more college. We fished salmon and albacore off the coast of California. During quiet moments on the fishing grounds I'd sometimes see Uncle Ture stare off into the distance. He seemed bothered about something. He told me what he'd had to do in the war. He was a Chief Petty Officer on a transport ship which took aboard dead and wounded. Sometimes Japanese suicide bombers dove near them. He and his men zipped corpses into bags. His men refused to zip a particular corpse, the arm raised somehow. Ture did it. This memory seemed to bother him. One day I walked along a dock in Morrow Bay, California with him. A fisherman passed Ture. The fisherman said, "Hello, Chief." Ture ignored him. Later, Ture told me the man had served under him in World War II aboard the transport ship with the dead bodies. "I don't want anything to do with any of that," he said. War shortages and war in general were not good. I wanted nothing to do with that. I never wanted to wear a uniform, be forced to wear clothing I did not want to wear. The war caused my Uncle Ture to have bad memories. I hoped I'd never have to spend one day in the military or in a uniform. After Pacific Lutheran College I took a job in Juneau where I worked for the Alaska Department of Fish and Game as an Accounting Clerk at the subport building across from the Alaska National Guard Armory. I examined reports filed by Alaska Fish and Game Licensing Officers. Since this involved revenue the Alaska Department of Revenue took over the F & G Licensing Division. The revenue people examined my work with numbers. They needed someone "up on the hill" in the main state office building to examine Alaska state income tax returns. A promotion, I took the job. Because of the Vietnam war the local Draft Board pulled Juneau guys left and right into the Army. I'd be called up any time.

Juneau Armory

He said, "It'd be a good move to get in the Guard, stay out of Vietnam. All you have to do is six months boot camp in Fort Ord and you're good to go." Though this would involve a uniform, I hurried to the Armory, asked if I could join. Let me share with you how I failed to qualify at Fort Ord as a rifleman. I'd been wearing the 1960s version of contacts. They were large and not so flexible, but useful when fishing albacore on the high seas with Uncle Ture. If I wore much needed glasses while working in the trolling pit, the albacore we pulled in would flop around on deck and splatter blood all over my lenses and I'd not see. Contacts were perfect. Clean ocean winds kept tears flowing around the lenses. Ashore, dust made them nearly impossible to wear. I'd suck on them to clean them. In Juneau, I lost these contacts down the sink. Unable to afford replacements, I visited an optometrist for cheap glasses. However, when I got them the prescription was either wrong or my eyes had changed while I waited for two weeks for my glasses to arrive on the steamship. At any rate, I couldn't see well. The optometrist said there was nothing he could do. I couldn't afford to buy another pair of cheap glasses. Fellow Guard members advised me not to worry. "The Army will fix you up with glasses," one of them said. So, at Fort Ord they checked my eyes, discovered I could not see and indeed said they'd get me new glasses. They did not. When it came time to qualify as rifleman with the M1, I aimed at the wrong guy's target. The training sergeant became upset on discovering I did not have Army issue glasses. He failed me as rifleman. This failure got back to Henderson in Juneau. For KP (kitchen police) we were "alphabetized." The trainees on KP with me were always the same guys. Their last names started with the letter B. I specialized in pots and pans. Once I had pots and pans down it was easy.

Fort Ord, Aug.1962. I'm second row, behind flag.

Once in awhile we'd get called back to Fort Ord for KP. We were considered lucky: we'd get to sleep in the barracks in an actual bunk and take showers. After boot camp, I returned to my job in Juneau. However, attending National Guard meetings continued to interrupt my lifestyle. On inspection a sergeant observed my belt was too long, looked sloppy; I must cut the belt to the proper size. He gave me latrine duty. The sergeants instructed us to shout out "No excuse Sir!" if officers chided us on any infraction whatsoever. One pleasant day when I was in a good mood I decided to get a haircut from one of the Officers. His dad owned a local barber shop where he worked. I sat in his barber chair, told him, "I need a haircut good enough to pass inspection." During the next formation this barber/Officer and Henderson examined my haircut and chewed me out for not having a military haircut. I had to think quickly. If I objected I'd catch hell. So I sounded off, “No excuse Sir!” eyes straight ahead. After a few seconds the Officers passed on. Nevertheless, more latrine duty.. A few in the Guard were heavy duty all night party guys. One snowy week-end the sergeants ordered us to don our over-whites and bunny boots. We'd maneuver this week-end out in the Mendenhall valley. Some of us filled our canteens with vodka to make the ordeal a little more digestible. However, I over-imbibed and tried to sleep in the middle of a snowstorm under a jeep. Immediately, a sergeant dragged me from under the vehicle by the feet. The next meeting, Henderson called me in his office and chewed me out for "incapacitating myself." He told me I'd never get promoted if I kept it up. A promotion in the Alaska National Guard didn't interest me, and I'd learned from other trainees in Fort Ord to never volunteer for anything. However, Henderson knew I worked with numbers and writing and had once been Editor of the Ketchikan high school newspaper. He made me Company Clerk. Now he knew where I was at all times: in his office right in front of him. This was okay because I could keep my mind on filing and typing morning reports, hang out in the office and do menial office tasks and hope the effects of last night's party would go away. Our platoon-sized infantry unit, Company C, 297th Infantry, became the 910th Engineer Co. (Combat) (Army) on January 1, 1964 as a result of an Alaska National Guard reorganization ordered by Governor Bill Egan.12 For us at the Juneau Armory, the military phrase of the day in our new role as Engineers was "be flexible." One of our Tlingit Guard members liked to look off in the middle distance and emit a sort of soliloquy with a tongue-in-cheek smile, and say quietly, "I'm flexible." He became one of the drivers in a convoy that prior to our two-week active duty requirement drove from Juneau to Anchorage, specifically to Camp Denali. This convoy left Juneau on March 8, 1964. The other Guard members, myself included, flew to Anchorage a few days later. The Alaska Marine Highway vessel Chilkoot ferried the convoy vehicles from Juneau to Haines. They couldn't make it through the mountain pass north of Haines, so the Alaska Highway Department plowed ahead. The convoy made a successful trip.

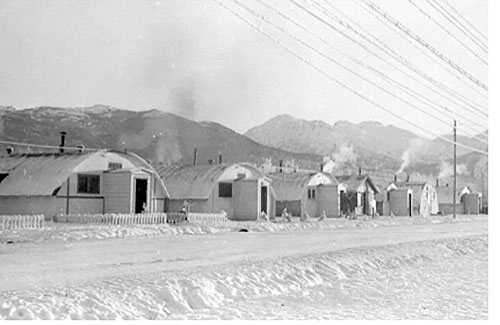

Quonset Huts at Fort Richardson. This annual training at first went normally. I heard some officers say the training exceeded the expectations of even the regular Army officers. At the end of the camp on Good Friday, March 27, 1964, Headquarters started closing down Camp Denali. Officers reviewed schedules for our departure. I did a few Company Clerk duties in a wooden hut which served as the 910th's camp Headquarters. Captain Henderson, a sergeant, an officer or two, and a corporal came and went throughout the day. Our Yukon stove kept our hut warm. A cot in an adjoining room offered rest for a tired sergeant, fast asleep. I had bronchitis, coughed often. Captain Henderson entered the hut and drawled that in his opinion the air inside was too dry. He placed a coffee can filled with snow on the stove to get a little humidity going and left. Distant band music drifted in an open window. I leaned against the hut's open front door and looked. This was a pretty nice afternoon. In the distance the glint of sun off a tuba caught my attention as band members in over-whites marched along. Suddenly, distant trees shook and swayed violently. A few seconds later the band fell to the ground. The ground moved towards me like ocean rollers, big waves, moving fast. They hit the hut. I couldn't stand, so I got down on my hands and knees and braced myself. The corporal stood behind me holding an ax. As the hut tossed about he strove to maintain balance but only succeeded in waving the ax a little too close to me for comfort. I yelled at him, "Get down on the floor. Get down. Drop the ax!"

JC Penney Building, 5th Avenue, partial collapse. The sleeping sergeant roared out of the adjoining room and began cursing and screaming at us for shaking his bed. But he stopped screeching as he realized this was something else. He, too, hit the floor so he'd not crash into the Yukon stove. The rocking continued for three, maybe four minutes. All we could do was hold on. It finally stopped. Oddly, we laughed. I do not think any of us thought this was actually funny. It just happened so fast none of us realized the importance of what had happened, only that we'd survived a big ride in an old flexible wooden hut. We learned later this was one big quake, probably one of the worst ones in the history of the North American continent. It tumbled Anchorage, made scars around Turnagain that'd remain for lifetimes. A lot of Anchorage folks had began their Good Friday at church, maybe looking forward to spending Easter with their families. For a lot of people, the quake began with a small shake. A few rationalized it'd be over in a second because shakers had happened before, no big deal. Some motorists might have thought they'd just gotten flat tires. People slipped on the ice. A few people in buildings figured a heavy truck had passed. Many heard a loud rumbling noise as lifting and tossing earth caused Anchorage to sway and split open. Stuff on shelves in stores tumbled, lights went out, kids cried, mothers screamed. Shoppers fled or tried to hold on to something - anything. It got worse. It registered 9.2 on the Richter scale. (Source: "Largest Earthquake in Alaska," Historic earthquakes, USGS, Click here, Web. 26 Oct. 2013) A tsunami took 128 lives. The quake itself killed 15. Earthquake effects were heavy in Anchorage, Chitina, Glennallen, Homer, Hope, Kasilof, Kenai, Kodiak, Moose Pass, Portage, Seldovia, Seward, Sterling, Valdez, Wasilla, and Whittier. Someone said the epicenter was about 75 miles southeast of Anchorage. The city sustained the most severe damage to property. Around 30 blocks of dwellings and commercial buildings took damage or got destroyed in the downtown area. The J.C. Penny Company building took damage beyond repair. The Four Seasons apartment building, a new six-story structure, collapsed. The Government Hill Grade School, sitting astride a huge landslide, was almost a total loss. Anchorage High School and Denali Grade School were damaged.

Damage in the Turnagain Heights area, Anchorage

The tsunami devastated towns along the Gulf of Alaska, and left serious damage at Alberni and Port Alberni, Canada, along the West Coast of the United States (15 killed), and in Hawaii. A huge wave entered Valdez Inlet The quake registered on tide gauges as far away as Cuba and Puerto Rico and shook parts of the western Yukon Territory and British Columbia, Canada. There were 1,350 Alaska National Guardsmen at Camp Denali. Our lives would be altered. The flexible wood hut we occupied received little damage. (Source: Richardson, "Alaska Guard: Alaska Army National Guard and other stories," 79) A radio station finally came on the air. Civil Defense requested Alaska Guardsmen and skilled volunteers to report for duty to restore power, water and communications.

Col. Fred O. Reger went at once to the War Room at the U.S. Army, Alaska, headquarters, and General Carroll went to the Public Safety Building in Anchorage to confer with Mayor George Sharrock. Within an hour, Adjutant General Carroll had alerted his Alaska National Guard troops to move to the downtown area where the earthquake had crumpled the Fourth Avenue business district. The Guard must keep an eye on damaged property and prevent looting. Headquarters for the Guard and Civil Defense were established at police headquarters in the Public Safety building. Guardsmen from the two Scout Battalions, the Third Battalion, the 216th Transportation Company, the company I was in, the 910th Engineering Company, the 10th Ordnance Detachment and the 36th Special Forces Detachment began moving to prescribed positions alongside active military forces.

We lived in the back of an ambulance like this one

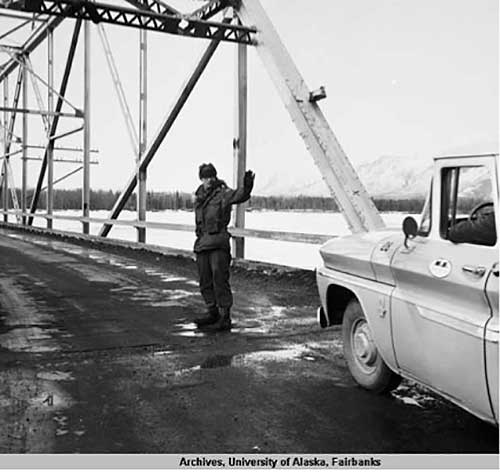

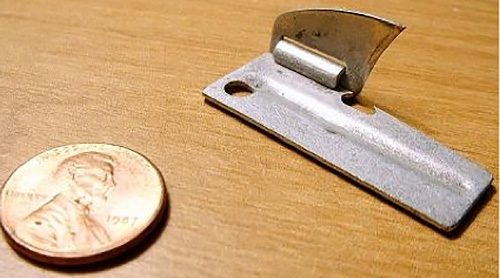

The sergeant asked for more volunteers. He needed someone to go up to the Knik River bridge to regulate traffic. I raised my hand. I found myself in the back of an ambulance which drove steadily for quite some time. I could see little of where we were going and had no idea where the Knik River bridge was. I'd actually never even been to Anchorage, wasn't sure how to get there. One of the Guard members had invited me to go to Anchorage with him before the quake but I refused because I had no money. Finally, the ambulance stopped. The Staff Sergeant in charge of me and another Guardsman opened the back. The Knik River Bridge wasn't far from us. A rusty 55 gallon oil drum with no lid sat a few meters away. The sergeant had us dig some rocks and sand and dump it in the oil drum and place a rusty grill on top. He said, "When you're hungry, use your p-38s, open yourself some of these c- rations. Pour this fuel into the sand and gravel and light it. It's how you're gonna warm up your food and make your coffee." We used Army issue water-proof matches to fire up the drum. Two State of Alaska engineers showed up and inspected the bridge. After some discussion they came over to us and said, "When drivers approach, stop them here. Tell them to wait 15 seconds while the vehicle in front of them crosses. Then let them pass. Don't let them go faster than 15 miles an hour." A line of vehicles appeared filled with families, suitcases, mattresses, tarps, coolers, boxes tied to the tops of the vehicles, windows partially open with skis sticking out, parents in the front, kids in the back, dogs and cats, trucks, RVs, on and on as far as I could see, all heading to us at the Knik River bridge. I stood in front of an approaching vehicle, raised my arm. The whole line stopped. I approached the driver. He rolled down his window and reached for me. He wanted to shake my hand.

Guardsmen regulate traffic.

One driver displayed anger at Alaska. He was heading back to Texas, get out of this "godforsaken place!" Some of the time I wore my M1 rifle; at other times I left it secured in the back of the ambulance. We'd switch off, open c-rations, warm the food and water for coffee, chow down, try to sleep. I'd sleep as best I could but sometimes my coughing kept the others awake. One night I heard a vehicle pull up. I heard voices, women's voices. They talked to the sergeant about something for free for us. I heard our sergeant politely thank them and send them on their way. The next morning the other Guardsman on duty said, "You know who stopped by?" "No," I said. "They were kinda like night ladies from Anchorage on the way out of town. They were gonna give us something for free." I said, "No kidding. What were they gonna give us?" I continued regulating traffic, putting in hours, taking scheduled breaks. One night I went on duty around 2 AM. I fired up the 55 gallon drum, made some instant coffee, got my M1, looked around.

P-38 Can Opener

Up the road I noticed a moving dot. It grew bigger, moving my way. After some time, the shadowy movement shaped itself into a man on foot trudging toward me along the side of the road. This was an old-timer on snow shoes carrying a back pack, a 30-30 strapped over it. I became aware of my M1, with no intention of using it of course, simply aware I had a weapon, too, even though I didn't qualify as a rifleman at Fort Ord. Eventually, he slogged directly across from me. I heard his snowshoes working, his breathing. He had a gray beard, flaps on his fur hat over his ears, was looking straight ahead, choosing not to look at me or acknowledge me. I thought out of friendliness (I'd been shaking hands with people in vehicles for hours) I'd say something to him. So I said in what I hoped was a pleasant way, "Where're you goin'?" I watched him cross the bridge. He became a distant shadowy figure, then a disappearing dot.

C-rations. Uncle Ture had pounded into me my duty to always do good work on the fishing boat. When the task at hand is done, look around for something more to do. Don't just stand there doing nothing. My Mother and Father wanted me to grow up in America believing I could do anything. They didn't talk about getting rich necessarily, but to try to do the right thing. The way I was living was not the right thing. I was stuck in a mindless waste. Memories of shortages in World War II Ketchikan, the air raid shelter, city blackouts, Canadian Allies, Lutheran catechism studies, Uncle Ture's horrible memories and the fact he did his duty anyway, his words to me on the fishing grounds about life - "All work is good work," he'd said to me - all these memories stayed with me. These inner implants are probably part of the reason I raised my hand and volunteered to do my duty with the Alaska National Guard despite my thoughtless vow to myself to never volunteer. Here at the Knik River Bridge I was sort of proud to wear the uniform of the Alaska National Guard. I was grateful for having a Commanding Officer like Captain Roger E. Henderson and sergeants who kept an eye on me and all the men in the 910th. After that night, my life spun off in a new direction. Whenever I drive over that bridge, I remember.

The Adjutant General of the Alaska National Guard, Thomas H. Katkus, as well as Director of Personnel, LTC Michael P. Seine, Alaska National Guard, instituted an excellent research project to locate the 1964 members of the 910th Engineers (Cbt) (Army), Juneau. It is hoped this humble memoir will bring to the fore this part of Alaska National Guard History on that day in 1964 and keep the names of those who made up this Company from fading. I include below Alaska National Guard members with whom I served during the 1964 Good Friday Earthquake. I apologize if I missed anyone. If I did, let me know. I do not have all the ranks and for that I also apologize. The list, I hope, will honor their memory. They served. Captain Roger E. Henderson

|

||