Effort to retake Attu and Kiska was 75 years agoEllis, Bartholomew, other locals, fought in the AleutiansBy DAVE KIFFER

May 21, 2018

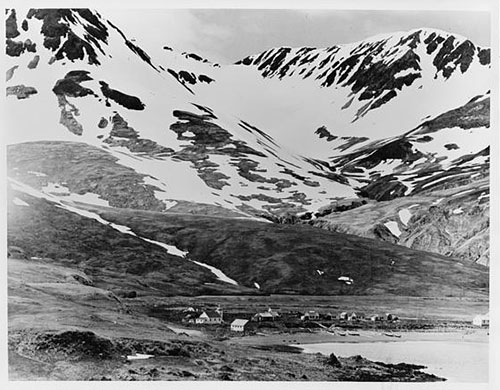

Japan had the held Attu and neighboring Kiska Island for approximately 11 months and a significant American effort was put in place to drive the Japanese from American "territory" even though the battle was clearly a backwater to the primary American war effort in Asia, Africa and Europe. When the Japanese invaded Attu and Kiska in June of 1942, there was concern amongst the American and Alaskan public that it was the beginning of a full scale invasion of America. But, in reality, the Japanese never intended for it to be any more than a temporary "diversion" and a long-term defense against American efforts to mount attacks on Japan from the Aleutians.

The original island invasion and the corresponding bombardment of Dutch Harbor was initially an attempt to get the United States to commit valuable war resources to the north and give the Japanese an advantage in their real target, Midway Island, in the central Pacific. But by the time of the attack, the US had broken the Japanese naval code enough to understand that the northern attacks were only a feint. Still, political and public pressure mounted to evict the Japanese from "American territory" and that led to the lengthy planning process to free Attu and Kiska islands. Attu had been in Japanese hands for approximately 11 months when the battle to reclaim it began on May 11, 1943. By the time it was over, on May 30, several thousand Japanese and American troops had died over an isolated 344-square-mile rock in the north Pacific that both sides agreed had little or no strategic value. Initially, when Kiska and Attu were invaded on June 6-7, 1942. US military planners had feared that the Japanese would develop long range bombers that could reach West Coast cities. But by the time a year had passed, it was clear that Japan wasn't close enough to developing such aircraft. The United States, though, was clearly on track with its B-29 program to developing a bomber that could easily reach Japan from bases in the Aleutians.

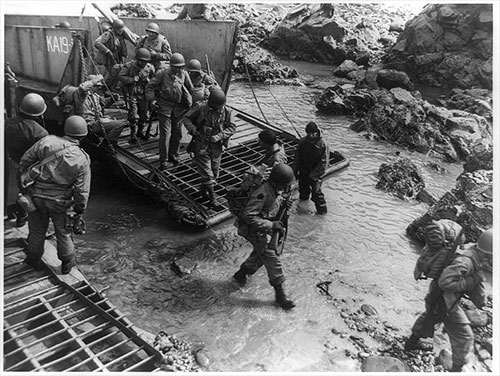

Dislodging the Japanese Army from the Aleutians took nearly a year of planning and also involved setting up a logistical chain that stretching more than 3,000 miles from Seattle to Adak. Originally, the American forces had planned to attack first Attu and then Kiska in August of 1943 when the weather was at its best and the fog and frost was less likely to cause logistical problems. But American intelligence uncovered plans the Japanese had to send a relief column consisting of four aircraft carriers, three battleships, seven cruisers and 11 destroyers to the islands to ward off an American invasion, and the timetable was moved up. Unfortunately, that change in the timetable severely effected the training and preparation of the invading force. Therefore, a significant portion of the Seventh US Infantry Division arrived on site fresh from desert training, unprepared for the cold weather it would encounter in the Aleutians. As a result, weather related casualties dramatically out paced combat related ones for the American soldiers. Frostbite and trench foot effected nearly one third of the US soldiers involved in the effort.

The Japanese had had nearly a year to set up their Attu defenses and they concentrated on a plan that did not include defending the beaches. Rather, the Japanese set up fire zones inland that concentrated resources on passes between the island mountains and control of the high ground which would allow them to repel the numerically superior forces that the United States was bound to commit to the invasion. When the invasion began, Japanese forces on Attu totaled just over 2,300. The American and Canadian invasion force totaled more than 11,000. Because the Japanese did not contest the beaches, US military officials were initially surprised at the speed that the soldiers of the 7th retook much of the island. But then, as the American troops tried to wipe out the inland pockets of resistance, it became clear it was in for a fight. Prying the Japanese out of the mountain passes and other entrenchments quickly bogged down and it took more than two weeks to get the upper hand, as the Japanese held out for the relief fleet that never came. Finally, on May 29, it became clear that rescue was not going to happen and Japanese commander Col. Yasuyo Yamasaki, led his remaining forces, estimated at more than 1,000 in a "banzai" charge. The charge caught the Americans by surprise and initially broke through the American lines, but then failed when the Americans brought their numerical superiority to bear. The Japanese literally fought to the death and only 28 Japanese soldiers were taken alive. American combat casualties in the two week battle were 549 dead and 1,200 injured. The American forces immediately turned their attention to the Japanese forces on Kiska Island 200 miles to the east. Kiska's Japanese garrison was estimated at more than 5,000 soldiers, twice that of Attu and the US Army estimated it would take more than 30,000 American troops to dislodge the Japanese, based on what had happened at Attu. So the invasion was set for August and US bombers blasted away at Kiska for the next two months.

Meanwhile, the Japanese high command had decided that holding onto the island was not worth the resources needed as the American forces continued to island hop their way across the Pacific. When the large American/Canadian landing force arrived at Kiska on Aug 15, 1943, they found the Japanese had left on July 28th. Even so the "invasion" did not go off smoothly. Allied forces suffered more than 200 casualties, most from friendly fire confusion and bad weather related incidents. Ketchikan residents were particularly interested in the Aleutian Campaign because two dozen Ketchikan men were involved in it. Commander Bob Ellis was in charge of the US Naval Air Station in Kodiak and flew missions to Kiska and Attu and several young Ketchikan men, including Ralph Bartholomew and Chuck Cloudy, were members of the 10th Emergency Rescue Boat Squadron, which was tasked with plucking downed aviators from the violent seas in the Aleutians. Bartholomew recounted the history of the 10th Emergency Rescue Boat Squadron at a conference on World War II in Alaska in 1993 in Anchorage. Shortly after the bombing of Pearl Harbor in December of 1941, the Army - which then included the Air Corps - decided to set up an aviator rescue squad patterned after what the Royal Air Force was doing in the English Channel. Lt. Gordon Donley came to Ketchikan to meet with the Coast Guard. They recruited a group of Ketchikan men for small boat crews. Bartholomew wrote that Ketchikan was a logical place to recruit boat crews because so many of the young men had experience around small boats through the fishing industry.

Originally, the group was the called the "Air Corps Marine Rescue Service," but then it was changed to the "924th Quartermaster Boat Squadron." "Our CO (commanding officer) was extremely distressed, to say the least, when Army officials insisted that only the Quartermaster Corps operated boats," Bartholomew wrote in 1993. "However, he was successful in changing it back later to the Army Air Force." The final name was the "10th AAF Emergency Rescue Boat Squadron." Bartholomew wrote that the Army set up barracks space in the Filipino bunkhouse at New England Fish Company over the winter of 1942 and then moved into the vacant Civilian Conservation Camp at Ward Lake in the summer. "That became the boot camp for our Army training as well as out classroom for the navigation, signaling and small boat handling classes," Bartholomew wrote. "Not long after our transfer to the Ward Lake CCC Camp, the military decided to move the Aleut natives out of their communities in the Aleutians and move them further away from to the war to Southeastern Alaska points. As our CCC camp looked like a good place to deposit some of those families, we again had to move, this time to the new Annette Island Army Air Field." After more training in California and familiarization with the squadron's new 104-foot rescue boats, the locals finally went to the Aleutians in 1943, just in time for the effort to retake Attu and Kiska. Bartholomew's group split up with most going to new bases at Adak and Cold Bay. Even after Attu and Kiska were liberated, the rescue boat squadron remained in the Aleutians for the duration of the war as the Army Air Corps used the new bases to attack northern Japan and the Japanese occupied areas in China as well as islands north of Japan. "The squadron participated in many rescues and life saving responses from climbing mountains, hiking across the tundra, transporting seriously ill tugboat crew members to shore hospitals, emergency calls to outlying weather and radar stations as well as the aircraft emergency ditching calls.," Bartholomew wrote in 1993. "When the P-38's were called on for experimental fighter cover for the B-24's bombing Paramushiru, they were pushed to the very maximum of endurance. One of their pilots made a comment that put our squadron into perspective, he said; "We knew the chances of being rescued by you guys were slim or none. But one thing we knew for certain was that you would always be out there looking, and that made the difference." A complete accounting of the local men who served in the Aleutians is not available. But the following were mentioned in Tongass Historical Society files as serving in the Aleutians during the War. Cliff Phillips, Robert Cawton, Everett Nelson, Mervin Baglien, Gordon Zerbetz, Phillip Moeser, Lloyd Stensland, Paulu Saari, Wendel Pitcher, Howard Royer, George Thorson, Billy Burns and John Grainger. When the war was over, Bartholomew, Cloudy and the others returned to Ketchikan. Years later some of the Aleutian rescue boat operators were among the first members of the Ketchikan Volunteer Rescue Squad.

On the Web:

On the Web:

Contact Dave at dave@sitnews.us Dave Kiffer ©2018 Representations of fact and opinions in comments posted are solely those of the individual posters and do not represent the opinions of Sitnews.

|

|||||||