By DAVE KIFFER September 06, 2012

Baranovich is credited with starting one of the first trading posts in Southeast Alaska and the first copper mine. He was also one of the first to appreciate Alaska’s fishery resources. He arrived toward the end of Russian era and lived for more than a decade in “America.” His descendants still live in Southeast Alaska. Baranovich was born sometime in the late 1820s or early 1830s near Trieste, in Dalmatia, which was then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. It is now part of Italy and near the Slovenian border. Ketchikan mining historian John Bufvers wrote in 1952 that Baranovich came to America as a “youngster” and then took part in the California Gold Rush of 1849. He later went north to British Columbia for the Fraser River Gold Rush in 1858 and the Cariboo rush of early 1860. The Tongass Historical Museum has a copy of an “agreement” between Major Malowauski and “Vincenzo” Baranovich to be the “co-partners in running the schooner “Langley” and freighting “the same” from the Port of Victoria to Ports elsewhere.” That agreement was signed in Victoria on Sept. 28, 1861. By 1865, he was in the Kasaan area and in 1867 he staked the first copper mine in Alaska, the Copper Queen. Alaskan historian Pat Roppel surmises that Baranovich – who was referred to as “The Slav” or “The Austrian” - probably entered Russian America by canoe down the Stikine from the Canadian gold fields. “There must be a fascinating but untold story surrounding the fact that this wandering prospector was able to secure one of (only) twenty-one coveted Russian American Company trading permits granted in 1865,” Roppel wrote in a 1970 edition of the New Alaskan magazine. Bufvers reported that Baranovich first noted a copper vein near Kasaan while paddling his canoe near Round Island.

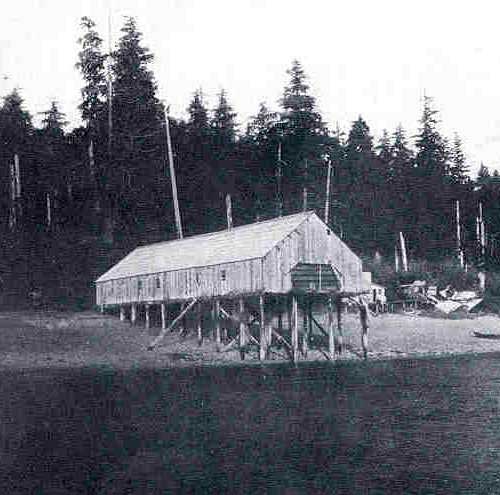

Baronovich Salmon Saltery -- The Oldest Saltery in Alaska

Bufvers noted that Baranovich’s trading post - which he supplemented by taking his ship, the Pioneer of Cazan, to villages up and down the coast - was located on south side of upper Kasaan Bay, about one and one half miles west of Sandy Point. Both Bufvers and traveling writer Eliza Scidmore report that Baranovich was married for many years to a daughter of Chief Skowl, the long time Haida leader in the Kasaan area. Mary Baranovich’s 1925 obituary in the Wrangell Sentinel, however, indicates she was the daughter of a “steward” at the Wrangell trading post and has no mention of Chief Skowl. Roppel, in the 1970 New Alaskan, wrote that Baranovich kept two households in Kasaan. “The larger one, built in typical Haida style was run by Mrs. Baranovich, according to old tribal customs,” Roppel wrote. “Since Baranovich was not accustomed to communal living, he built a smaller house of logs and rough hewn planks for his immediate family.” In addition to developing the trading post and staking the copper claim, Baranovich was also a “pioneer” in the Alaska fishing industry, according to Roppel. She noted that during the Russian American years, little interest was paid to Alaska’s fishing resources. “As a result of Baranovich’s marriage he was able to obtain from his father-in-law the fishing rights on one of the best streams,” she wrote, adding that Baranovich used a native fish “trap” to school the salmon in the creek so they could be easily caught. Baranovich built a small saltery in Kasaan to process the salmon and ship them south. The Baranovichs had nine children, one of which, Joe , went on to be elected a Representative in the Alaska Territorial Legislature and a prominent Ketchikan businessman, A daughter, Celia, attended Carlisle Indian School in Pennsylvania, where she was a classmate of Jim Thorpe. Most of the Baranovich children remained in the Prince of Wales area and several were in the fishing industry.

In 1885, Eliza Scidmore, a traveling journalist, published “Alaska: It’s Southern Coast.” In the book, she visited the Kasaan area. Baranovich had been dead for several years, but he still cast a big shadow. “Karta or Kasaan Bay has been a famous place for salmon for a score of years, and is best known locally as the Baranovich fishery,” Scidmore wrote. “Old Charles V. Baranovich was a relic of the Russian days and a character of the coast…he disturbed the serenity of the customs officials by the steady smuggling he had kept up from over the British (Canadian) border.” Scidmore wrote that Baranovich was extremely colorful, even by the colorful standards of the times. “He would import all kinds of stores, but chiefly bales of English blankets, by canoe, and when the collector or special agent would penetrate to this fastness of his, they found no damaging proof of his store and only a peppery, hot headed old pirate, who swore at them roundly in a compound language of Russian, Indian and English and shook his crippled limbs with rage,” Scidmore wrote, adding that Baranovich was also suspected of selling liquor to the Indians, and that a revenue cutter once arrived in Kasaan Bay to investigate. According to Scidmore, Baranovich invited the crew to dinner and then “dozed and smoked” while the US officials searched his buildings and the native village. They found nothing. “Baranovich gave them a good dinner and towards the close a bottle of whiskey was set before each officer, and the host led with a toast to the captain of the cutter and the revenue marine,” Scidmore added. Huber Howe Bancroft, in his 1886 book, “History of Alaska, 1730-1885” also referred to Baranovich’s brushes with the American “revenuers.” “Baranovich was accused in 1875 of smuggling blankets, hard bread, and flour,” Bancroft wrote. “The evidence was conclusive but there was no jurisdiction in Alaska and it was not considered worth the expense to indict him in the courts of Oregon or Washington Territory.” In her book, Scidmore also reported that the natives of Kasaan generally viewed Baranovich very warily. “While Baranovich was cleaning his gun one day, it was accidentally discharged and one of his children fell dead by his own hand,” Scidmore wrote. “The Indians viewed this [deed] with horror and demanded that (Chief) Skowl take his life as punishment. As it proved to be an accident, Skowl defended his son-in-law from the charge of murder and declared that he should go free. Ever after that the Indians viewed Baranovich with a certain fear and ascribed to him that quality which the Italians call the ‘evil eye.’“ Arriving on scene in Kasaan several years after Baranovich’s death in 1879, Scidmore also reported that “the old pirate” had had an extensive collection of weapons, including dueling pistols and “fowling” guns that he had gained through trading over the years. “Baranovich was a man with a long and highly colored history by all the signs, but he died a few years since with no biographer at hand and his exploits, adventures and oddities are now nearly forgotten,” Scidmore wrote. “The widow Baranovich still lives in Kasaan unwilling to leave this peaceful sunny nook in the mountains but the fishery is now leased to a ship captain, who has taken away the fine old flavor of piracy and smuggling and substituted a regime of system, enterprise and eternal cleanliness.” Roppel notes that Scidmore got taken in by the apparent “up and up” at Kasaan. “Little did Miss Scidmore suspect that this ship captain, the very one who was extending such courtesies to the journalist, had come to the conclusion that if Baranovich could get away with smuggling in this remote place, then he could do some of the same,” Roppel wrote in 1970. She wrote that the ship captain smuggled opium from British Columbia to Kasaan where it was packed in salmon barrels, which were then shipped back to Puget Sound. An informant eventually blew the whistle. Mary Baranovich would live until the age of 90 and would die in August of 1925, according to the Wrangell Sentinel.

Ship loading Canned Salmon at Kasaan Cannery

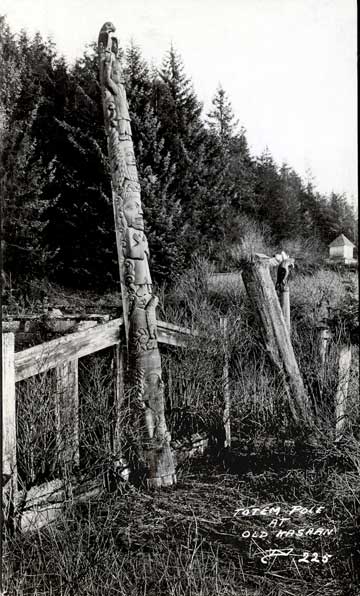

Edward Keithahn’s 1945 book “Monuments in Cedar” tells the story. “The Chief Skowl totem pole was erected by the great Haida chief Skowl at Kasaan in the early (18)80s and had since been removed to Ketchikan’s city park,” Keithahn wrote in 1945. “The eagle surmounting the pole is Chief Skowl’s totem,” Keithahn continued. “ Beneath it is the figure of a Russian saint. The third figure, apparently emerging from the clouds, is the face of the Archangel Michael, and beneath it the Russian bishop. Next comes another eagle, beneath which is the figure of Skowl’s son-in-law, Vincent Baronovich … Baronovich was an English subject and, together with Skowl, held in contempt the ‘Yankee Government’; so it is unlikely the lower eagle represents the United States which had recently purchased Alaska. “Skowl’s daughter, Mrs. Vincent Baronovich, largely financed the carving and it was no doubt for her sake that her husband’s figure was included. He died in 1879 and Skowl died in the winter of 1882-83,” Keithahn added.

On the Web:

Contact Dave at dave@sitnews.us

Publish A Letter in SitNews Read Letters/Opinions

|

||||