Father Duncan died 100 years ago'Apostle of Alaska' was 86By DAVE KIFFER

September 03, 2018

William Duncan's death, on August 30, 1918, was noted in newspapers throughout the world. He was known far and wide as the "Apostle of Alaska." His role in founding two different Christian "utopias" in British Columbia and Alaska had made him famous - and somewhat infamous. Duncan's role is founding the Alaskan community of Metlakatla has been well documented ( See The Founding of Metlakatla, SITNEWS, August 7, 2006). Prior to coming to Alaska in 1886, Duncan had founded a similar community in Metlakatla, British Columbia, a village not far from the present site of Prince Rupert. After a childhood in Yorkshire, England, Duncan joined the Church Missionary Society (CMS) and in 1856, at the age of 24, Duncan was sent to Port Simpson (now Lax Kw'alaams) in north western British Columbia, not far from the then Russian America border. Port Simpson was the primary Hudsons Bay Company trading post in the region and Duncan soon became concerned that life at the Fort was negatively affecting the Tshimshian Natives. Duncan had decided that the best path forward for the Natives was to assimilate into Anglo culture, but at a location that was remote from contact with the Anglo culture and its many negative tempations. Duncan convinced 60 Fort Simpson Tshimshian to follow him to a location 25 miles south of the fort, near the present day site of Prince Rupert which would not be developed until half a century later ( See "Prince Rupert, Hays Orphan, Looks to the Future," SITNEWS, February 28, 2007) Shortly after, more than 200 other Natives joined Duncan at the new site. In setting up his "model" community, Duncan stressed industry and the renunciation of traditional Native ways in order to more easily assimilate into the Anglo culture. Among the new rules for the community were giving up alcohol and gambling as well as face painting and traditional Native healing practices. The potlatch ceremony was specifically banned. Residents were also required to send their children to school and to attend church. They were required to live in Anglo style homes and wear Anglo clothing. Duncan's hold over the new community was almost immediately strengthened when a small pox epidemic swept communities along the North Coast and more than 500 people died at Port Simpson. Only five died in Metlakatla and Duncan told the villagers that it was God's favoring that had generally spared the community. Unfortunately, Duncan's methods and his general ignoring of broader church rules were rankling his Anglican superiors. At least one attempt was made to recall him to England, which he just patiently ignored. Duncan was also beginning to deviate from church teachings in a variety of areas. Reportedly, Duncan ignored the sacrament of communion in Metlakatla because he was concerned that the Natives would misunderstand it, especially in relation to the cannibalism of some of the North Coast tribes that Duncan and other missionaries were working to eradicate. Most notably, Duncan was trying to erase much of the Tshimshian culture because he wanted to assimilate them into western culture as completely as possible. A seemingly minor thing that rankled the Canadian Anglican authorities was the fact that Metlakatla residents referred to Duncan as "Father Duncan" even though he was a lay leader, not a minister. Eventually, Duncan began to see his superiors in Canada and England as the "enemy." He looked north of the border, where the United States was only minimally taking control of the new Alaskan territority. Duncan used connections he had established with the US federal government and obtained a "reservation" including Annette island and several smaller nearly islands for a second "Christian Utopia."

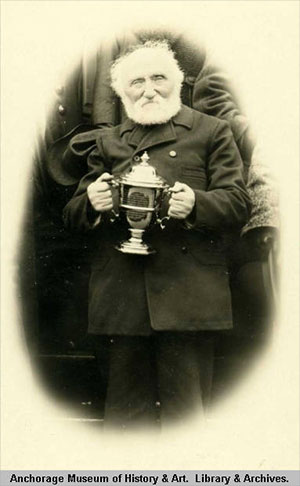

This time, some 800 people joined him on the voyage to Alaska to found the community that he initially called "New Metlakatla." The primary reason that Duncan gave for the transfer to Alaska was that Natives were unable to "own" property in Canada and would be in Alaska. This led some of the residents of the new community to believe that Duncan - who was now in is 50s - was planning to release some of his autocratic control over the community. But that was not to be, at least for the first 20 years in Alaska. After the founding of New Metlakatla in 1886, Duncan's community immediately became one of the largest in Alaska. The 823 people listed in the 1890 United States Census made it fourth to Juneau-Douglas (1,623), Sitka (1,190) and Karluk (1,123). In 1890, Metlatkatla was significantly larger than Loring (200) and "Kichikan" (40). Duncan would also play a role in the founding of Port Gravina, across the Tongass Narrows from Ketchikan ( See "The Village of Port Gravina, SITNEWS, February 4, 2006 New Metlakaltla was a financially strong community under Duncan's leadership boasting a sawmill, cannery and other businesses. But as time when on, the residents became more and more disenchanted with Duncan's autocratic leadership. By 1910, when Duncan was approaching 80, portions of the community were in open rebellion. Residents petitioned the Alaska government to come into Metlakatla, audit the community finances, and take over operation of the community schools. In 1911, territorial Governor Walter Clark visited the community to hear some of the concerns first hand but took no action. Then in 1913, Governor John Strong made a second visit to the community in which he reportedly heard from more than 60 residents demanding that Alaska take over the education of the children because - they contended - Duncan was punishing those who did not agree to his methods and he preventing "self determination" by the residents. The federal government then began administering the community schools. An attempt was made to get the Bureau of Indian Affairs to oust Duncan from his leadership position in the community, but no action was taken because by then Duncan was in his early 80s and was frequently so ill that others ran the community for him. Then on Aug. 30, 1918. Duncan died at 86. Ketchikan's "Daily Progressive Miner" covered Duncan's funeral in its September 2, 1918 edition, noting that more than 1,000 people turned out for the ceremony outside the largest church in the territory, a building that Duncan had built more than 30 years before. "A mixture of the solemn and curious native ceremonies blended with those of the usual church services held by Christian churches all over the world, marked the obsequies held yesterday at Metlakatla, when the body of the late Father Wm. Duncan, was laid in its last resting place in the churchyard, beneath the shadow of the largest church in Alaska, a fitting and living monument of his life work among the natives of the north," The Daily Progressive Miner reported. "The first services, according to the old native custom, were held on Saturday when a few intimate friends of the deceased missionary gathered in the living rooms of his house to witness the placing of the body in the casket. Rev. Van Marter, of the Methodist Episcopal church of Ketchikan gave an address on the life of Father Duncan, and native speakers paid tribute to his wonderful work with them. A short song and prayer service concluded the ceremony. Sunday the public service was held at eleven o’clock the body was brought out of the house and placed on a pedestal erected in front of the home of the dead man. Here the procession formed, headed by the band and followed by the casket, carried on the shoulders of a number of stalwart Metlakatlans. About one thousand natives and visitors followed the procession which proceeded very slowly to the strains of the funeral march played by the band, all around the outskirts of the town back to the church." During Duncan's final years there had been rumors that he was hoarding money from the community for his personal use. But the trustees of the estate told the Daily Progressive Miner that all of Duncan's estate was left to the community to propagate additional mission work. A century after his death, Duncan would probably find much familiar and much unfamiliar about the community he founded and ruled for three decades. Alcohol is still banned in the community, but gambling as a foothold with a small casino operating a variety of slot machines. The Tshimpshian culture that Duncan tried to erase has made a strong comeback and is the focal point of the community's growing tourism industry. The Tsimpshian's still control their resources, primarily timber and fishing, separate from state of Alaska regulations as the community remains the only Native reservation land in Alaska. Most ironic is the fact that Duncan's grand church, still bearing his name, is controlled by a different Christian denomination than the one that Duncan championed his entire life.

On the Web:

Contact Dave at dave@sitnews.us Dave Kiffer ©2018 Republication fee required. Representations of fact and opinions in comments posted are solely those of the individual posters and do not represent the opinions of Sitnews.

|

||||||