Remembering a local legend40 years after his death, Ed Todd remains fresh

|

|||||

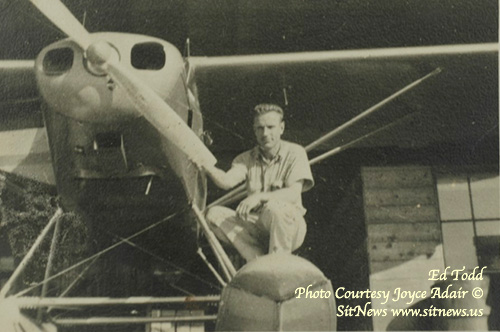

Ed Todd, date unknown |

Todd’s Air Service advertisements in the Ketchikan Yellowpages made that abundantly clear.

“We fly when YOU want to fly.”

In fact, it was common knowledge around town that there were three kinds of weather. Good weather. Bad weather. And Todd weather.

“No matter that the wind was gusting to 40 knots, or that dense rainfog forced motorists to use headlights at noon or that the sun had already set behind the western mountains,” Pilot/journalist Gerry Bruder wrote in his 2014 book “Seaplanes Along the Inside Passage,” which featured an entire chapter on Todd called “Barefoot Hero.”

“In marginal situations, when we stood by the office window, weighing the risks against the potential rewards, the sight of anyone else’s floatplane taxiing out into Tongass Narrows often goaded us into launching on of our own planes for a look; weather that was good enough for a neighboring air service was good enough for us. Todd exerted no such influence when he flew by, however. He had different standards and belonged to a different class.”

Indeed, even forty years later, locals can recall flying with Todd in situations that might have been inadvisable, at best.

“He told my Aunt Anna if the sea gulls can fly so can him,” Marlene Steiner said recently.

But even when the seagulls weren’t flying Todd was. Which sometimes meant “improvising” by either flying at very low altitude or even not “flying” at all.

“Dad and I were in Metlakatla for a dive job,” Dean Parkhurst said recently. “Ed was supposed to pick us up but it was terribly foggy that day. Off in the distance we heard a plane, it was Ed step-taxiing his way to the dock. Hop in, he says, it’s flat calm today. And away we went, step taxiing all the way back to town.”

“Weather permitting a phrase he was not familiar with” his daughter Joyce Adair said recently.

It seemed that if someone needed to get somewhere, Todd was always willing to give it a go.

“When I was 16 and working at National Bank of Alaska, I was asked to find someone/anyone to hire to fly Elmer Rasmusen to Metlakatla,” Connie Williams said recently. “It was your typical ugly Ketchikan late fall day, sideways rain. Ed Todd was the only one who said ‘Yes, have him out here in about 20 minutes.’ I dropped Mr. Rasmusen off, Mr. Todd told me to be back in 3 hours to pick him up. I was right there at the appointed time, only to have Mr. Rasmusen get in my car and state to me ‘Never again,’ I didn't know if he meant never aqain in this weather, or never again with Ed Todd. Good times.”

Of all the pilots in Ketchikan, Todd was known as the best of getting into – and out of - lakes - a valuable skill as many people – Todd included – loved fishing in the numerous, secluded lakes in the area.

Ed Todd owner of Todd’s Air Service, date unknown |

“My ex-wife (Maureen) and I and a couple others had flown into Heckman Lake,” Mike Crosby said recently. “We were to leave on a certain date... that date came and the weather was unbelievable. Well, not really having been born and raised there. But it was nasty. Rain, wind, low hanging clouds not a one of us at the Forest Service Cabin expected to be picked up, but just in case we packed everything up. Lo and behold a short time we hear power and here comes Todd. He pulls into the beach, we load up our gear, climb into the plane and again the weather is nasty, the lake isn't all that long and we have it loaded.”

Most, if not all, pilots would have emptied out the plane to make sure that it could get back out of the lake. But Todd was not most pilots.

“One of us said, 'Todd can you get off?' ” Crosby continued. “ 'Let’s find out' and he guns it. Bounces that plane down the lake finally at what seemed the last second he lifted off, I do believe if I had opened the window I could have grabbed a few spruce needles. As we were flying towards town, being in the front seat I notice that one fuel tank is on dead empty and the other needle is bouncing on empty. I asked Todd if we had enough fuel to get to town. His response was, 'heck yes. I planned this. How do you think we got off the lake? If I'd have been loaded with fuel no way. So I brought just enough.' We made it! Scary. My ex, who wasn't a drinker said after mine and Todd's conversation. I think I need a drink.“

Terry Carlin remembered a similar “close scrape” on Gravina Island.

“Todd flew us into Long Lake on Gravina for deer hunting,” Carlin said recently. “Can’t remember how many of us or how many deer on the trip out but the plane was loaded very heavy. As Todd was pulling the plane as far back on the weedy shoreline for maximum takeoff distance one of us asked him if we would clear the trees at the end of the lake (stupid question but we were nervous). His reply: “Maybe”. Crap! We cleared them by about 20 feet.”

Al Turner also survived several entertaining lake offs and landings with Todd.

“He would always say, if it floats, it will fly,” Turner noted.

Walter Erickson remembered a particular Todd takeoff from Checats Lake.

“We loaded up and went airborne into grey nothing,” Erickson said recently “He started circling until he knew he had enough altitude to clear the cliffs. We could see nothing outside the plane. He followed the tree top level until we were over water and then flew a few feet off the waves. Suddenly he pulled hard on the controls and flew over a boat that we hadn’t seen. We made it back obviously but that was the most unusual and frightening flight of my life.”

While all pilots learned to fly close to the water when the fog rolled in, Todd naturally flew closer than most.

“One time my dad had to get out to Annette Bay and it was so foggy no one was flying there is about 12 ft of visibility above the water Ed Todd flew my dad out flying about 12 feet off the water dodging boats and buoys to get him out there,” Jef Dillard said recently.

Todd was also not concerned about flying after dark, an often dangerous task because the frequent cloud cover prevented the moon from illuminating the water.

“One night I was working at the Standard Oil dock loading barrels on a barge," Keith Stump said recently. “It was foul weather gear and turned into a windy, rainy dark night as Todd made a number of flights to Metlakatla. In the dark, Todd would taxi down the Narrows to the oil docks, spotlight on looking for floating logs, then turn into the wind and take off. Half an hour later he would return, make a low pass over the water looking for logs, then coming back around and land in the pitchblack night. I'm sure there were four or five flights like that while we worked late into the night.”

Todd also had an almost supernatural ability to find his way amongst the canyon-like fjords in all manner of inclement weather.

“I flew back with Todd from a trip to the Wilson Arm area, and along the way there's a box canyon,” Stump said. “Todd was talking about an old mine there and he was looking out the side of the plane trying to locate it, rather than looking forward as the high mountainside at the end of valley was fast approaching. No way to climb over it. As he was pointing out the mine shack that finally came into view, and while all I was thinking about was that we would be flying right into the mountainside, without even looking forward, he banked hard right into another valley that you couldn't see until you were right there. Scared the bejesus out of me. Apparently he did this regularly, even though I heard that more than a few times he had to spend some time cleaning out the inside of his plane.”

Like most of the pilots of his day, Todd also liked to have a little fun, buzzing close to the ground.

Sandy Adams Watt remembers that Todd was a friend of her father, legendary miner/pilot Kelly Adams. When Todd found out that Kelly Adams’ middle name was “Gaylord” he would fly low over the house, open the plane door and shout “Gaylord” to get Kelly’s attention.

Suzan Thompson noted that Todd was particularly taken with the two eleven-story apartment buildings in Ketchikan’s West End, the Tongass Towers and the Marine View. One day, Todd took the five-year-old Thompson on a quick flight over town.

“He flew me downtown, past the Marine View and/or Austin Towers, and I looked in one of the windows and saw a lady cooking at her stove,” Thompson said recently. “That memory stays with me. We must have been awfully close to the building!”

Bobby Bromley had a similar experience.

“One flight into town with Todd, coming in from the north. we were over the channel headed towards his dock, when he banked left. We were at the same height as the 10th floor of the (Marine View). He went straight at the restaurant on top and people inside were looking nervous, when a few stood up, we banked hard to the right headed to his dock again,” Bromley said recently. “Of course, we made the usual approach, buzzing the Coast Guard dock. I flew with him quite a few times, most first flight in the morning and last at night. In the morning he would just be getting out of the water from his dip in the channel. He only wore a jumpsuit and slip on shoes on the flights. Was proud to have had the experiences of flying with him.”

Befitting his reputation as a “grown up child” Todd was always trying to introduce youngsters to the joy of flight. Several current pilots got their first taste of the air with Todd and that often included sometime behind the wheel. Frequently Todd would just hand the reins of the plane off in mid-flight – sometimes just telling the surprised passenger to “steer strait toward that mountain ahead,” stretch his sandal-clad feet out and pretend to take a nap.

“He used to fly me and my brother, Robert Shedlosky out to Boat Cove every summer,” said Paula Shedlosky Peterson recently. “He wore just swimming trunks and flip flops. He would land in the middle of the cove, jump out, swim to our Grandfather’s house and they would drink a cup of coffee and visit, while we sat in the plane. Finally Grandfather (Pete Myking) would row his skiff out to the plane, Todd would get in, we’d get out and onto the skiff and off he’d fly. He was such a character! Sometimes he’d let us ‘fly’ or so we thought, and he’d get low to the water or trees and then swoop up and tell us we need to go to flight school before he’ll let us fly again. We really thought we were flying!”

Harley Bray, who worked for Todd when Bray was in high school, said that Todd also enjoyed ‘helping out’ teenagers in other ways as well.

“Four of us were going to fly into Heckman Lake for Spring Break,” Bray said recently. “My Dad was going to transport us and all of our gear to Todd's for the flight. Some of our 'supplies' included beverages that Dad wouldn't have approved of, so we took those supplies out to the hanger the day before. After offloading, Dad decided to stick around to see us takeoff, creating the dilemma of loading the supplies (Beer and Boones Farm) without Dad seeing. Ed winked at us and took care of that issue, by inviting Dad into the house to see his newest velvet paintings, of which he collected. We finished the loading.”

But flying was not always just fun and games for Todd. In the highly competitive local air taxi industry, passengers were money and Former Forest Service worker Jim O’Toole remembered a time when competing pilot Herman Ludwigsen apparently “poached” two of Todd’s potential passengers on Prince of Wales Island.

“Just as we were finishing loading them, Todd showed up and, when Herman pulled away from the empty dock with a full plane, he knew that Herman had stolen his customers and was pissed,” O’Toole said recently. “He pulled alongside Herman's plane and stayed wing tip to wing tip with him as Herman taxied. Herman really poured the foot to that plane but Todd stayed just feet away from Herman's wing tip until both planes were in the air when Todd peeled off. Herman was grinning the entire time and I wish I had been around the next time those two old veteran pilots ran into each other.”

With all the stories to tell, what was Todd’s own “hairiest adventure?” He shared it with the Ketchikan Daily News’ Southeastern Log in January of 1976.

Todd was hired to ferry a Stinson from Anchorage to Ketchikan In 1954, long before he formed Todd’s Air. He was working for Ketchikan Packing Company at the time and was “bored” with wintertime “idleness.”

Since it was February the weather across the Gulf was extremely poor and the situation was complicated by the fact that the Stinson had only recently been converted to floats. Interestingly enough, the younger Todd – he was only 35 at the time – tried to wait out the weather. Meanwhile, warming weather in Anchorage began to melt the snow on the Merrill Field runway that would allow Todd to take off. After 10 days there were patches of rock showing through and Todd could wait no longer.

“I got off okay,” he told the Southeastern Log. “But I could feel those rocks ripping the floats during the takeoff.”

He briefly landed on Lake Spenard and checked the floats, which didn’t seem too badly damaged, so he took off for Cordova. When he arrived in Cordova he realized the floats were significantly damaged. He tried to patch them up with gunny sacks and melted tar.

"I thought I had the floats sealed pretty good, but just to be safe I refueled and warmed the engine up on deck so I'd be all set to go when they dropped me back in the water,” he told the Log "I tried to take off downwind out the harbor but couldn't get off the water. When I started to get out into the sea I had to stop, turn around and take off the other way, upwind. I knew then that I still had leaks.”

The extra weight of the water that had leaked leaking into the pontoons, also burned up the airplane’s fuel quickly. It was snowing heavily, and he began to look for a place to put down but with 12 foot seas everywhere there were few options. There was a military field at Cape Yakataga and he fought the weather there but when he arrived, he decided to keep going – even though he was practically on fumes – because he was already “late” in delivering the plane to Ketchikan.

Fighting through the wind, dark and snow – and often only 20 to 30 feet above the ocean – he made it to Yakutat. He beached the plane near the town and – being Ed Todd – went ashore and promptly joined in at a dance at the local Alaska Native Brotherhood hall. After the dance he went out to secure his plane against the rising tide and then waited to see if it would continue to float. It did.

He slept in the plane overnight and refueled in the morning. Once again the extra weight of the water in the floats made it difficult to take off, but eventually the Stinson got airborne. He had good weather down to Sitka and decided to stop there for the night. The next morning the storm had returned and he immediately regretted not flying on to Petersburg the night before when the skies were clear.

Once again, he had to fly low to the water and try to follow the shoreline. When he was in Rocky Pass near Kake, the sky closed in and he was flying completely blind, barely able to see the water and unable to find the shore without running into it. There were large waves below him, so landing was not option. He just had to keep going ahead and hope for the best.

Finally, he came across a fishing boat in what appeared to protected waters. He landed, taxied up to the boat and found he was in Union Bay, not far from Myers Chuck on the Cleveland Peninsula.

“I was elated,” Todd told the Log. “This was home ground to me. I knew every rock' and tree from here on in."

Twenty minutes later he was at the dock in Ketchikan.

"I was never gladder in my life to get home," he said, "To be out of that damn thing and know that I had brought the man's airplane to him.”

Of course, Todd’s flying adventures were only part of his story.

If you mention Todd’s name, someone is bound to say, “wasn’t he the guy who used to swim naked across Tongass Narrows every day?”

Well, yes, and no.

Stump says that Todd would often go swimming off his dock, sometimes clothed, sometimes not. It became quite the show for the customers at the nearby Narrows Restaurant and, rumor has it, that the seats facing Todd’s Air were in high demand by some of the restaurant’s female clientele.

Todd’s daughter, Jackie Tyson, says that her father usually wore a skimpy bikini bottom that his wife had made for him but that it became pretty threadbare over time and lost its color enough that people thought he was naked.

I once asked Todd about his “skinny dipping” and he laughed.

“Well, partner,” he said. “That has been a bit exaggerated.”

But there were enough verifiable sightings to indicate that Todd was not adverse to swimming naked in the cold waters of Tongass Narrows.

Todd was always a bit of health fanatic and his daughters remember him doing 1,000 jumping jacks and and numerous pulls ups nearly every day.

His swimming exploits apparently got serious – he did indeed swim back and forth across Tongass Narrows nearly every day – after his wife Helen died when her plane crashed on a lake on Annette Island in the mid-1960s. The lake was later named Helen Todd Lake in her honor.

She survived the crash and swam to shore but then died of exposure on the shoreline. Todd reportedly vowed that he would not let that happen to him and that he would train his body to be in good enough shape to survive such an event.

And, besides the exercise, that led to Todd’s unusual flight “uniform.”

He rarely if ever wore shoes, if it got extremely cold he would don sandals. He sometimes would wear a Hawaiian type shirt that he tied at his waist. He frequently wore what would later be called “short shorts.” If it was really cold, he might put on a pair of overalls, but he would then just as likely take them off when the plane was warmed up and at altitude. Usually after handing the controls to one his passengers for a few minutes.

When asked, Todd would say that wearing fewer clothes “toughened up his skin just a bit.”

I once asked him about the shoes.

“The last thing I want, partner, is my shoes or boots to fill up with water and drown me.”

That never happened, of course, but time and a mountain eventually caught up to Ed Todd.

When he left Ketchikan on the morning of October 5, it was to do a little goat hunting on the mountains near Ketchikan. Bray says that goats were something that Todd particularly liked to go after.

“One time when it was slow 'at the office' he took me along to pick up a Hyder fare,” Bray said recently. “On the way, we flew thru Misty Fjords, so Todd could check out the mountain goats. He was planning on coming back that weekend to get one and wanted to know where the big billies were. I swear he was trying to pick off the goats with the wingtips.”

Todd was known to frequently unnerve passengers by suddenly diving toward mountains to point out goats, deer, bear or wolves that his keen eyesight had spotted.

On Oct. 5, 1978, he said he was going goat hunting and took off at 7:30 am. Later in the day, he was to pick up two fishermen at Fish Creek, south of Ketchikan. When he didn’t return, Dixie Jewett, his partner in the business and one of the first female commercial pilots in Alaska went looking for him. She met up with the fishermen, who had not seen him. She searched a few likely places, expecting that he had probably had some sort of engine trouble and had hunkered down.

That was what everyone else in the Ketchikan flight community assumed as well.

Ed Todd had more than 30,000 hours of flight time. In all that time he had dinged up a few planes but had never seriously hurt himself nor any passengers. It was simply not possible that the invincible Ed Todd was experiencing anything more than some minor annoyance in the nearby wilderness.

The weather had been unseasonably nice the day Todd flew out, nothing bad could possibly have happened.

Soon a storm blew in and search efforts were curtailed. Part of the problem was that Todd hadn’t been clear where he was going to look for goats. In all likelihood it would be in Misty Fjords but he had also been also known to hunt on Cleveland Peninsula and the mainland behind Revillagigedo Island as well. Searchers would have to comb hundreds of miles on three sides of Ketchikan.

Soon, the local rescue community led by Dick Borch and the Ketchikan Rescue Squad were out in force in addition to the Coast Guard. The weather remained bad and it was difficult to go up the inshore passes and valleys. Besides, everyone agreed, Todd was simply stuck somewhere, waiting out a rescue. That was the only possible alternative.

“Todd was an indestructible hero,” Bruder wrote in 2014. “As indelibly a part of Ketchikan as Deer Mountain and Tongass Narrows.”

1978 was a particularly bad year for aviation in Ketchikan. Before Todd went missing, there had been four fatal crashes in the area. Twenty-five people had died. More people would die in additional crashes in November and December. It was the worst year for aviation fatalities in Ketchikan’s history.

For four days, pilots zigged and zagged through the wind and clouds and rain, looking for any trace of Todd or his distinctive orange and white Cessna 185. Finally, on Thursday, there was a break in a weather. Near a small unnamed lake a few miles from Big Goat Lake in Misty Fjords. Don Ross saw wreckage on a hillside. It was Todd’s Cessna, N70269. A few minutes later, Jewett flew into the same valley and also spotted the wreckage.

“The wreckage lay vertically strewn on the steep slope from an elevation of about 3,700 feet – almost with throwing distance of the ridge’s crest,” Bruder wrote in 2014. Ken Eichner brought a search party on a helicopter but could get no closer than half a mile away. It took the party four hours to reach the plane.

“After cutting the seat belt and extracting Todd’s overalls-clad body from the cockpit,” Bruder wrote, the crew kicked the plane’s remains down the hillside, so it wouldn’t accidentally fall on them as they climbed down with Todd’s body. “As one searcher slung the body over his shoulder, a large jackknife fell out of the overalls and clattered onto the rocks. Goats hair and dried blood covered the blade.”

As with many crashes in the Alaska wilderness, there was no obvious cause.

Jewett suggested to Bruder that Todd had possibly had trouble getting out of the lake.

“He just never throttled back,” she told Bruder. “Once, coming out of the lake, he even ran up on the muskeg, but he kept barreling along till he got her in the air. He always kept boring ahead.”

The National Transportation Safety Board could come to no official conclusion on the cause. There were no mechanical problems with the plane and nothing physically wrong with Todd.

“To people throughout Alaska, the puzzle was not why it happened, but that it happened at all,” Bruder wrote. “Pilots felt especially humbled. Some of us had regarded Todd as a larger-than-life figure, a heroic knight invincible before all dragons and ogres. If HE could fail on a seemingly innocuous mission, no amount of savvy could protect the rest of us from the menaces of the bush.”

Todd was cremated and his body buried with his wife in Bayview Cemetery.

Todd’s Air did not survive Todd’s Crash. The Ketchikan Daily News reported a week later that the Federal Aviation Administration had pulled the air taxi’s license because it was in Todd’s name and he had never incorporated the company which would have allowed someone else to assume the certificate. Jewett eventually left flying and moved to Montana first and then Oregon where she has become a well-respected sculptor and artist.

Todd’s family did manage to get the certificate reinstated, but eventually the company was sold to another pilot. The location of the airline, just south of Ketchikan passed through several hands, but eventually was bought by Dave Doyon’s Misty Fjords Air which still operates from the site.

Todd’s memory remains bright in the dozens of residents who offered to share their stories of him for this story.

Although he was born in Seattle in 1919, his family had moved to Ketchikan when he was a boy and he had grown up here, making him one of the earliest truly “local” pilots. Old timers remember that his mother Alma owned a store on the south end of town, where Todd would later base his air service.

His daughters, Jackie Tyson and Joyce Adair, remember a father who was driven to fly, hard-working but also a great enjoyer of life. They both worked for him at different times and were – as teens – sometimes embarrassed by his antics.

“I imagine he had a very healthy heart, which kept him from getting cold as he flew in his bikini at times (to my utmost chagrin) or in cut-off shorts,” Tyson said recently.

“How I miss those days.”

Adair, who admitted that when she was young flying with her father sometimes “scared her to death” agreed.

“I’ll never forget those awful skintight cutoff jeans shorts and that purple aloha shirt tied up around his waist,” She added.

They both remember he loved poetry and would recite Robert Service at length, particularly “The Cremation of Sam McGee.”

Bruder noted that another favorite poem of Todd’s was Service’s “The Men That Don’t Fit In.”

“Ask Todd if he was ever going to retire from bush flying and live a ‘normal life’ and he’d open his mouth in mock astonishment, point a questioning finger and rant histrionically,” Bruder concluded.

“There’s a race of men that don’t fit in.

“A race that can’t stay still.

“So they break the heart of kith and kin,

“And they roam the world at will.

“They range the field and they roam the flood,

“They climb the mountain’s crest;

“Theirs is the curse of the gypsy’s blood

“And they don’t know how to rest.”

On the Web:

Columns by Dave Kiffer

Historical Feature Stories by Dave Kiffer

Contact Dave at dave@sitnews.us

Dave Kiffer ©2018

Publication fee required.

Representations of fact and opinions in comments posted are solely those of the individual posters and do not represent the opinions of Sitnews.

SitNews ©2018

Stories In The News

Ketchikan, Alaska

Articles & photographs that appear in SitNews may be protected by copyright and may not be reprinted without written permission from and payment of any required fees to the proper sources.

E-mail your news & photos to editor@sitnews.us

Photographers choosing to submit photographs for publication to SitNews are in doing so granting their permission for publication and for archiving. SitNews does not sell photographs. All requests for purchasing a photograph will be emailed to the photographer.