Japanese immigrant was an early

|

|||

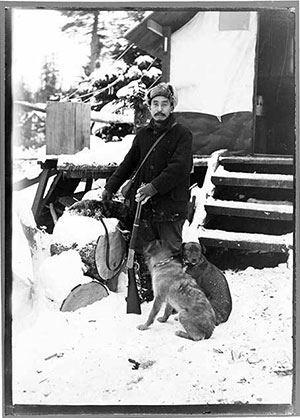

Fhoki Kayamori with rifle, two dogs and an otter; winter. Yakutat, Alaska. Time period 1913-1939. |

But the second Alaskan World War II related death occurred just a day later, in Yakutat, when Japanese immigrant Fhoki Kayamori committed suicide.

Kayamori was a fixture in his adopted hometown of Yakutat for nearly 30 years. The reason? The immigrant that everyone called the "Picture Man" took hundreds of photos of the people of the community. And it was that hobby that eventually created the circumstances that lead to his death at 64.

Kayamori was born in 1877 in the village of Dembo, today part of Fuji City in central Japan. In Japan, just coming out of centuries of feudal isolation, he was a child without prospects. Although he was born to a wealthy family which owned a paper mill, farm lands and a department store, he was the fifth of eight children and the second son. He would not inherit much, if any, of his family holdings.

When he became an adult, he served the required three-year military term and then served in the reserves. In 1903, it was likely that he would be called up to fight as Japan was in a dispute with Russia that eventually led to the Russo-Japan War of 1905.

Whether he left to avoid the war or not, Kayamori turned 26 on board the steamer Iyo Maru on the way from Yokohama to Seattle. Japanese men were being encouraged to come to America in those days, particularly on the West Coast, as there were many jobs in the growing salmon cannery industry going unfilled. Particularly in light of the fact that there were strict limits on Chinese workers, who had filled most of the cannery positions up to that point.

According to Margaret Thomas' 1915 book "Picture Man," Kayamori arrived in Seattle with $87.10 and a steamer ticket to San Francisco in his pocket. Although he initially settled in San Francisco, the great quake of 1906 likely disrupted his plans to stay there, as did increasing anti-Asian racism in the Bay area. He was back in Seattle within a few years. By 1910, he is listed in census records as living in Seattle's Welcome Hotel and working as a "cleaner and passer" at a cotton dye works.

In 1912, he decided to move north. Although the Klondike Gold Rush had long peaked, there was a new “salmon” rush about to explode. In 1909 J.R. Heckman had invented the floating fish trap and that single innovation would cause the salmon canning industry to boom across Alaska. By 1911, salmon canneries were already earning record profits and, according to Thomas, 19 new canneries opened in 1912 in Southeast Alaska alone.

“The West Coast’s anti-Asian attitude contributed to profits by forcing Asian immigrants to accept almost any job, no matter how low the pay” and that led to mass exodus north of Asian workers, Thomas wrote.

Whatever the specific reason – and Kayamori left behind very little about his personal life – he headed north to Yakutat to work in the new Libby, McNeil, Libby cannery.

"Kayamori held various jobs at the cannery," Thomas wrote. "Yakutat fisherman Oscar Frank Sr. remembered him as a cooker at the row of giant barrel-shaped retorts. On rainy days, Kayamori pitched down dented or leaky cans to the children playing under the stilted cannery."

In 1991, Yakutat elder Paul Henry wrote to the Alaska Historical Library that Kayamori was a quiet person who often worked in the company store, waiting on customers. In the 1930s, company records show that Kayamori was also working as a night watchman for a yearly salary of $500.

Before long, Kayamori had gained a nickname in the community. It started with the children who called him "Picture Man." Soon everyone in the village called him that.

"He took pictures at every event in the village," Elaine Abraham told Fern Chandonnet for Chandonnet's 2008 book "Alaska at War: 1941-1945, The Forgotten War Remembered." "We were at a Christmas play put on by the church, and Mr. Kayamori was up there in front with a camera, you know the kind that goes POOF in front of you. POOF."

"He was just part of the whole big family in town," MaryAnn Paquette told Thomas. She remembered him as a small man with a moustache and cap that he wore over his gray hair.

Like many people in Yakutat, Kayamori lived on the barter system, trading photographs for many items and also trading things like soy sauce and sweets for salted salmon and sealskins items. Although Kayamori never returned to Japan, he did stay in touch with family members there over the years and also received many items from people he knew in Seattle.

Abraham also remembered visiting Kayamori's small cabin.

"Japanese voices pattered from Kayamori's radio as the children sampled foreign cookies, crackers, and soft-shelled nuts from tins labled with a spidery script," Thomas wrote. "For Christmas he once gave Paquette and her sister a miniature camera to share."

Over time, residents say, Kayamori photographed just about all the several hundred residents of the community. He photographed them in formal situations and in less formal ones. He captured the life of Yakutat from the 1910s to the early 1940s.

Essentially, Kayamoir was a loner in the community. He never married, which was probably a direct result of United States government limits on the “picture bride” phenonenom which had been a popular way for Japanese men in American to get wives from Japan.

There is little evidence that Kayamori had close friends among the residents of Yakutat, but he did have a Japanese countryman, Y. Miyake who also lived in the community. Miyake died in 1931 and was buried across the bay. Kayamori photographed the deceased Mikake in bed and in a canvas covered coffin. 1931 was also the year the first plane - piloted by Bob Ellis of Ketchikan - landed in Yakutat. The first actual “road: was also built in the village that year.

Throughout the 1930s, the rest of the world seemed remote from Yakutat. But some residents noted that Kayamori was interested in the Japanese war in China.

"In Yakutat, Kayamori posted a map of China on a wall in his house and marked the progress of the Japanese military invasion of China with pins, remembered resident John Bremner," Thomas wrote.

"What are they fighting about, rice?" Bremner said he asked Kayamori.

"The Chinese never say 'no' to the Americans," Kayamori replied, according to Bremner. "They only say yes."

But as the world marched slowly towards World War II, the outside world became more interested in Yakutat.

"In the run up to World War II, it was this stretch of open coastline that disquieted military minds," Thomas wrote. "By 1940, weekly transports were delivering supplies and soldiers by the hundreds to Yakutat. For a while. the cannery served as a barracks. Construction of a landing field was soon on its way."

Because he was foreign born, Kayamori was required to register under the Alien Registration Act. He complied but that did nothing to allay concerns that the man who photographed everything in and around Yakutat could possibly be working as a foreign agent.

In October of 1940, the head of the Federal Bureau of Investigation, J. Edgar Hoover, wrote to Juneau officials requesting the names of "persons who should be considered for custodial detention pending investigation in the event of a national emergency."

According to a Freedom of Information request that is now on file in the state archives, Kayamori's name was on the list with the notation "Is reported to be an enthusiastic photographer and to have panoramic views of the Alaskan coast line from Yakutat to Cape Spencer."

The FBI investigated Kayamori by contacting the Yakutat post master about correspondence Kayamori had with his relatives in Japan. The postmaster told the FBI that Kayamori often sent letters to his mother, but received no mail in return.

In writing her book, Thomas contacted many residents who knew Kayamori. Although most said they believed the photographer was not a spy, they conceded that there were a lot of rumors in the community.

"The people start to think, well, he'd been a spy all the time he was here," Oscar Frank told Thomas.

"Stupid hysteria," countered Wayne Axelson. "I have nothing but praise for the guy. He was a tremendous individual. I bet my bottom dollar that Kayamori was no spy."

By mid 1941, charges and counter charges were flying back and forth between the United States and Japan and a Japanese naval officer was charged with spying in California and deported.

In Yakutat, military officials warned the population that war was coming and that an invasion of the area by Japanese forces was possible. Tension in the community was high. And invasion drills began to be practice. Families were also instructed on keeping their windows covered with blankets to make the community less visible at night from the sea.

"To stress the need for vigilance, the military staged an air raid one day," Thomas wrote. "A plane circled behind the Pacific-facing settlement, cut its engines and bombarded Yakutat with leaflets warning of similar Japanese attacks."

The military and some concerned residents began to eye Kayamori even more suspiciously.

"Kayamori's guilt or innocence hardly mattered anymore," Thomas wrote. "He was Japanese. Soldiers in Yakutat emphasized the point by beating up the sixty-four year old and stealing the change from his pockets. 'They hushed it up,' said MaryAnn Paquette. 'But everybody in town knew what happened.' "

On December 6, Kayamori's name was noted on a federal government list that the War Department was considering of "suspect" individuals.

Then the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor.

When word of the attack reached Yakutat, residents gathered to talk about it. Abraham told Thomas that Kayamori was the only one not at the gathering. According to Chandonnet's book, a search party went to Kayamori's cabin. He was sitting in a chair, dressed in a suit. dead. Although no autopsy was done, a local military doctor determined that Kayamori had poisoned himself.

In 1992, that doctor, Jack Karel, wrote a letter to Thomas.

"I saw a photograph of him in a (Japanese) Navy uniform," Karel wrote. "We did find evidence of an attempt to burn some document."

Kayamori died, as he had mostly lived, alone.

There was no funeral. Kayamori was buried across the bay, near his friend Miyake. Later a navy ramp was built over the gravesite.

"That's the wartime," Bremner told Thomas. "They don't worry about Kayamori."

But that was not the end of Kayamori's story in Yakutat.

More than three decades after his death, many of his glass negatives were found abandoned in an attic in Yakutat. Many had been damaged, but in 1976, two copies were made of each of the nearly 700 remaining images.

One copy went to the state archives and one copy for the people of Yakutat. Copies of Kayamori's photos now adorn several public buildings and many private homes the community that he called home for more than thirty years.

Editor's Note:

U.S. Census records indicate Mr. Kayamori's first name is Shoki not Fhoki; however, the Alaska State Library notes his first name to be Fhoki in their files. According to Dave Kiffer this apparent error has been brought to the attention of the state by several historians; however, the state still maintains the correct first name of Mr. Kayamori to be Fhoki not Shoki.

On the Web:

Fhoki Kayamori Photographs

Alaska State Library-Historical Collection of Fhoki Kayamori photographs

On the Web:

More Columns by Dave Kiffer

More Historical Feature Stories by Dave Kiffer

Contact Dave at dave@sitnews.us

Dave Kiffer ©2017

Representations of fact and opinions in comments posted are solely those of the individual posters and do not represent the opinions of Sitnews.

SitNews ©2017

Stories In The News

Ketchikan, Alaska

Articles & photographs that appear in SitNews may be protected by copyright and may not be reprinted without written permission from and payment of any required fees to the proper sources.

E-mail your news & photos to editor@sitnews.us

Photographers choosing to submit photographs for publication to SitNews are in doing so granting their permission for publication and for archiving. SitNews does not sell photographs. All requests for purchasing a photograph will be emailed to the photographer.