When Fur Farming was Alaska's third biggest industryHundreds of farms dotted islands in SoutheastBy DAVE KIFFER September 12, 2021

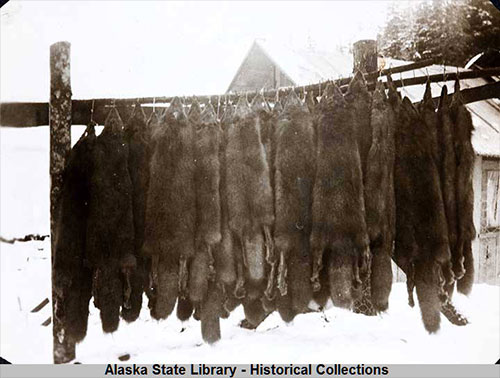

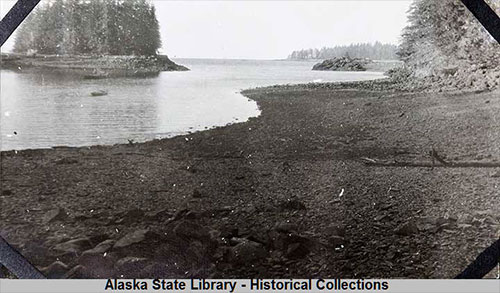

Fences and wire and sometimes dozens of rotting cages near broken down houses or occasionally larger buildings. It is the remains of what once was the third largest industry in Alaska. One that burst on the scene in the 1920s and had pretty much disappeared in barely a decade, leaving only the debris of numerous get rich quick schemes that never did. In the 1920s, one of the most common mammals in Southeast Alaska wasn't even a native species. There were more than 10,000 arctic or blue foxes in hundreds of small island farms from Dixon Entrance to upper Lynn Canal and Yakutat. Their forebearers had been brought south from northern Alaska to breed and make money.

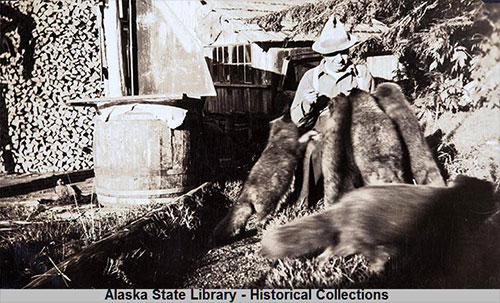

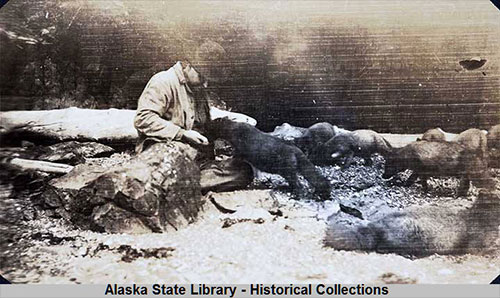

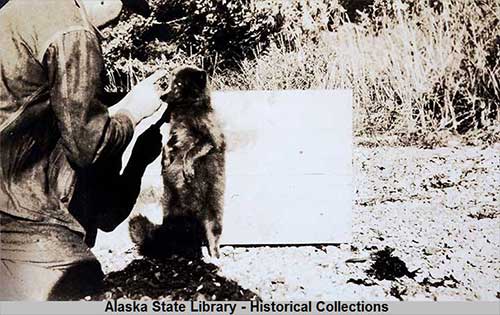

Later, many of the farms would switch to native mink species because of changes in public taste after the Depression and the simple fact that mink were smaller. easier to handle, and lent themselves to larger, cage farms. A booming world-wide economy in the so-called Roaring Twenties fueled a market for fur and that market drove hundreds of Alaskan entrepreneurs into fur farming, an industry that promised "get rich quick" but ended up delivering on "get poor quicker" before it flamed out when the Great Depression hit in the 1930s. The fur farm industry boomed and then busted when pelt prices dropped by 90 percent worldwide. The fur industry was what had originally attracted Russians to Alaska in the 1700s but while there was some hunting of Aleutian and southwestern foxes, most of the Russian interest was in fur seals. As the fur seal and sea otter numbers began plummeting in the early 1800s, the first rudimentary fox farms began to pop up in places like Kodiak and Cook Inlet as the Russians captured wild foxes and held them in pens. The idea was fairly simple. Bring a number of "breeding pairs" to a secure location, often a small, isolated island. The pairs would breed and soon the population would double and then triple. By 10 months of age, the younger foxes, called kits, could be sold for their fur. The foxes grew quickly in the Alaskan environment and, depending on the color of their fur, the pelts could be worth hundreds of dollars each. The 1929 book "Alaska" by Lester Henderson reports on some of these earliest efforts for commercialize the breeding, back just after the turn of the 20th Century. Most were unsuccessful because large amount of food was needed to support the farms, some of which had 50 or more breeding pairs. Most of the remote islands where the fox corrals were located did not have enough natural food sources for that many foxes. It was expensive to ship in feed and many farmers tried to supplement the feed by netting large numbers of salmon. One fur farmer, near Juneau, reported to federal officials that it took upwards of 400,000 pounds of salmon each year to keep his charges fed.

For the first 40 years of American control of Alaska, there was little interest in fur farming, but then a rise in fur garment prices around the turn of the 20th century changed things. In 1904, the US Commerce Department began allowing potential fur farmers to lease small islands along the coast of Alaska for farms that would encompass the entire island and not require pens to hold the animals in. A decade later, in 1914, E. Lester Jones, a deputy commissioner in the US Department of Commerce. visited Alaska primarily to report to Congress on the various fishing industries, but he also looked into the nascent fur farm industry. He noted that - in the territory - fur farming - then primarily fox farms - was "creating more than ordinary interest." But he also saw some negatives as the industry tried to grow. "Owing to the fact that few of the men who have engaged in this business have sufficient knowledge of the conditions necessary to raise foxes in captivity successfully, there have been many failures and few successes," Jones reported in December of 1914, adding that because of high prices "men have been misled into thinking that all they had to do was purchase a few foxes and soon begin to reap the benefits by receiving large sums for their sale."

Jones noted that even though some had received large sums for prime animals it was not a sign of a healthy market condition. He compared it to seeing a dog breeder get a huge return on puppies from a championship dog and then assuming all that all puppies would get a similar return. He said approaching the market from that standpoint would only bring disaster. Jones noted that anyone interested in fox farming had: 1. To be Industrious and willing to endure hardship. In 1904, the feds had approved leases for fox farming off the coast of Alaska, with leases ranging from $200 to $250 a year for five years. Jones estimated that beginning farmers would need at least $3,000 in capital ($89,000 in 2021 dollars) to get started and to last the four years needed before significant revenues started coming in. In his report, Jones suggested the government offer 10-year leases because five years was too short for most farmers to turn much of a profit before the lease was open to bid again.

After a decade of lease availability, Jones noted that there were less than 100 fox farms operating in the territory in 1914. He said his conclusion was the lease price was too high, the lease term was too short and that many of the islands in the territory did not have a sufficient natural food sources to support 100-200 foxes. Bringing in feed for the fox was extremely expensive for the farmers. Within a couple of years, the world was engulfed in World War I and the market for expensive, farm raised furs disappeared. But when the war ended in 1918, it only took a couple of years for the demand to return, especially as the world economies recovered in the early 1920s.

A sign that fur farming was becoming a "thing" was when it was accorded a lengthy feature in the September 1923 edition of National Geographic magazine. The article was called "A Northern Crusoe's Island" and was written by Margery Parker. Although the story was ostensibly about an isolated fox farm on Middleton Island, 100 miles south of Cordova, it focused more on the isolated lifestyle of the farmers and the shipwrecks they encountered and how they grew all their own vegetables. Parker reported that the Middleton Island foxes generated between $175 and $350 a pelt depending on quality. She noted the farm had sold 59 pelts in 1922. Soon articles on fox farming were popping up in the all the media of day. There was even a 1925 silent movie - long lost - called the "The Farmer's Fatal Folly" that was "set" on remote Alaskan island fox farm and involved a love triangle between the farmer, his wife and a hired man. The media stories about the fox farms further fueled interest in the furs which would be unabated until the Stock Market Crash of 1929. The first fox farms in Southeast Alaska began in 1901, even before the formal land leasing program. James York planted 30 pairs of blue foxes on Sumdum Island near Juneau and Mrs. George Scove started a smaller farm on Patterson Island on the east side of Prince of Wales Island near Ketchikan.

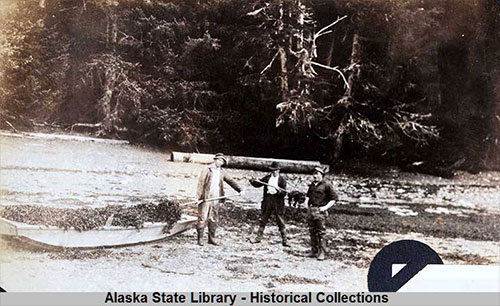

By 1923, there were more than 200 farms in Southeast Alaska and the Alaskan Weekly Newspaper proclaimed that the region would have eventually have "more than 1,000 farms" because it was so well situated. But it never quite obtained those levels. For one thing, the blue foxes that were used to populate most of the islands in Southeast were not as valuable as the silver and white furred ones up north. In general, blue pelts would go for around $100 while lighter colors would fetch up to $250. The speed that it grew created a very unregulated industry, with only a handful of federal game officials to monitor it. Poaching was common - especially on the isolated island farms - as new entrants tried to build up their stock by pilfering other people's foxes. It was the "law of the West" in the industry and sometimes farm owners felt they had to take the law into their own hands. One of the most famous incidents involved the San Juan Fox Farm at Sisters Island on Pybus Bay on Admiralty Island. The caretaker was named Ole Haynes and on March 5, 1923, his wife noticed a small boat land on the opposite side of the island, according to Sarah Isto in her 2012 book "The Fur Farms of Alaska."

There were two men with a tent, traps and rifles. Haynes went to a nearby island farm and recruited some reinforcements. They staked out the intruders' tent and caught one of the men with a dead fox. The man dropped the fox and ran inside the tent. Haynes later told a coroner's jury that he saw a rifle pointed at him before he fired. One man, Billy Gray, who was reportedly from either Ketchikan or Metlakatla, was struck by a bullet and killed. Haynes reported the shooting to authorities in Petersburg. The coroner's jury ruled that he had fired in self-defense. Overall, in the 1920s, fur farming briefly became the third largest industry in Alaska, after fishing and mining, according to the Alaska Department of Fish and Game history website. The peak was 1928, when more than 250 fur farms were operating in Southeast Alaska alone. For decades afterwards, it seemed like one could find the remains of old fur farms on any small island they visited in the region. There were also numerous fur farms on the outskirts of larger communities. There were five fur farms on the highways north and south of Ketchikan. The largest was one owned by the Anderes family near where the Saxman Seaport is now. When the market crashed, it crashed hard. In the 1986 Alaskan Journal, Janet Klein noted in " Farming For Fur" that pelts that had sold for $100 in 1930, were down to $11 in in 1932. The industry struggled on until World War II, when it was declared a "non-essential" industry and most of the remaining farms closed. But not all. In 1951, there were still 24 farms operating in the Tongass and Chugach National Forests. One of the largest belonged to Ernest Anderes near Saxman. Anderes' fur farm had up to 3,000 animals - mostly mink - at one point. A similar farm run by Earl Ohmer near Petersburg reportedly had nearly 4,000 animals, also mostly mink. Both farms continued to operate through the 1950s and both closed shortly before Alaska Statehood in 1959.

Anderes' younger sister, Lillian Greuter, grew up on the Saxman fur farm. "I just remember how loud the animals were," she said in an interview several years ago. "They howled and howled and howled." Because of the location, the Saxman animals were permanently caged and not allowed to run free like at the smaller farms on the isolated islands. In her 2012 book, "Fur Farms of Alaska", Sarah Isto wrote that territorial and state officials had never been completely sold on the financial viability of the larger farms. "Anderes' and Ohmer's farms were the last large fur farms in Alaska," Isto wrote. "Only small partnerships and family operations survived (statehood)." By 1966 only three mink farms and one fox farm remained in the state. The last fur farm in Alaska, near Delta Junction, closed in 1993, according to Isto.

On the Web:

Contact Dave at dave@sitnews.us Dave Kiffer ©2021 Publication fee required. © Representations of fact and opinions in comments posted are solely those of the individual posters and do not represent the opinions of Sitnews.

|

||||||||||