Gravina: A Tale of Two IslandsBy DAVE KIFFERAugust 14, 2021

Yes, we take the airport ferry and we fly out from the airport. Maybe we have driven to the end of the "Road to Nowhere" or we have gone deer hunting on High Mountain. Residents of a certain age still talk fondly of the community picnics at Black Sands Beach. But in general, for most area residents, Gravina is a like a prop to Ketchikan. Something to stare at on a sunny day, but not much else. Of course, there is more to Gravina than that. For example, did you know that Gravina is two different islands? Well, not now, but it used to be.

First off, there are three distinct parts to Gravina that are all geologically separate, according to the 1973 federal report "Geology of Gravina Island, Alaska." There is the eastern side, which is similar to the geology of Revillagigedo Island. Then there is a lowlands that extends from Bostwick Inlet all the way to Valenaar Bay. Then there is the western part of the island which has more in common with both Annette Island and Prince of Wales geologically. At some point, say in the late Triassic or early Jurassic periods, what we now know as Gravina was part of two separate land masses that only later drifted together as the continental plates moved. And even after that happened, there was a time when the two sides separated again as rising ocean levels between ice ages flooded the lowlands from Bostwick to Valenar. That is why that area has a significant amount of ocean silt that was deposited millions of years ago. Of course, the entire island was buried under glaciers during the last ice age, as was most of the region, which explains the generally rounded nature of the mountains of Gravina, according to the 1973 federal report. The report goes into great detail about the island, even explaining why, like Revilla, it looks like it would have lots of gold and silver ore (hundreds of quartz veins) but despite dozens of mining attempts over the years, not much gold has been found. Of course, there is much more to Gravina than its ore lodes, or relative lack thereof. The human history of Ketchikan's neighbor is as long as Ketchikan's when you start to look into it. Historically, Taanta Kwaan Tlingits had summer fish camps on the island but no permanent settlements. When the Spanish explorer Jacinto Caamano passed through area in 1792 he named the area the " Gravina Islands" in honor of Spanish naval officer Federico Carlos Gravina y Napoli. When English explorer Capt. George Vancouver surveyed the area in 1793, he applied the Gravina name to the single island. Gravina Island is roughly 21 miles long by nine miles wide. Let's start at Gravina Point, which is across from the southeastern tip of Pennock Island. Ketchikan historian Pat Roppel published "An Historical Guide to Revillagigedo and Gravina Islands Alaska" in 1995 and most of the following information comes from that source. Many of the coves and bays on the island were initially explored in the 1890s and 1900s as residents came looking for gold and silver. There was even a brief "oil rush" in 1910 when Jim Bratstone - who had oil experience in Wyoming and Texas - claimed to have found oil near Nelson Cove, but that quickly petered out when no one else could confirm his findings.

Gravina Point was the location of "Snag Harbor" which was the site of a homestead in the 1910s, but it is much for famous for an incident on August 9, 1994, when the Holland America cruise ship Nieuw Amsterdam ran aground in heavy fog at 6:20 am. The ship was refloated at 7:20 am and returned to Seattle. None of the 1,200 passengers or 500 crew members were injured, but the ship sustained more than $2 million damage to its hull. The islands of Blank Inlet were the site of several fox farms when that industry swept through Alaska in the 1920s and 1930s and Black Sand Beach was a very popular location from at least 1915 through the early 1960s. Cannery scows would be used to ferry hundreds of residents to beach which had warmer water because the dark colored sand trapped more heat. There is now a state marine park encompassing the area around the beach and the borough has plans for a trail to the beach from the end of the South Gravina Highway (the Road to Nowhere). Blank Point, at the mouth of Blank Inlet was also a popular location for moonshining back in the prohibition days with multiple stills operating, at least until the authorities shut them down. Bostwick Inlet is the next big indent on Gravina and as noted above, it is part of a lowland that splits the island in two all the way to Valenar in the north. It was a popular place for cabins in the early years and also area that has peaked interest of miners because of visible quartz veins in the hillsides. Bostwick has also been a key crabbing site for locals for decades. Just beyond Bostwick is Seal Cove where prospectors found enough copper to open up a mine in 1899 and mine the area until copper prices collapsed in World War I. Leading early Ketchikan citizens H.C, Strong and O.W. Grant were involved those efforts. There was also a very well- known incident in 1900 when a crew at the mine tried to thaw some frozen sticks of dynamite on a stove. The explosion killed one and seriously wounded three others. Dall Head at the Southwestern tip of Gravina also saw a lot of mining activity in the early parts of the 20th century and was a prominent location for fish traps up until the traps were banned in 1959. Dall Bay was also the site of a state land sale in the 1980s and quite a few remote cabins are located there. The western shore of Gravina on Clarence Strait was also a significant location for floating fishtraps from the 1920s to the 1950s. Some maps show up to 20 traps between Dall Bay and Valenar. It is also a popular "drag" for commercial salmon fishers. There was a fair amount of prospecting even into the 1970s on the ridges over places like Nelson Cove and Grant Cove, which were the main bays on the Clarence Strait side of Gravina. Grant Cove was named for the aforementioned O.W. "Six Shooter" Grant. Valenar Bay, at the northwest end of Gravina has been a popular spot since the 1890s amongst miners, loggers and homesteaders. There were also fish traps in the area which remains a popular location for local sport fishers. Initially copper deposits attracted prospectors but they didn't pan out. Neither did a clay deposit called "glacial mud" that led to the formation of the Ketchikan Brick and Tile Company which sold stock to many residents and promised to set up several "kilns" to process the clay. Although several area homesteaders, most notably a Mrs. Holden, eventually made pottery in Valenar, the commercial promise of the deposit was never achieved. Beginning in 1905, the USFS allowed homesteads and homesites in the area and another state land sale in the 1980s opened up more land. Art Almquist logged the hillsides above Valenar in 1956 and also logged part of the valley back toward Bostwick in the early 1960s. More recent logging efforts, primarily on Mental Health Land Trust and University of Alaska land have extended roads into the Valenar area.

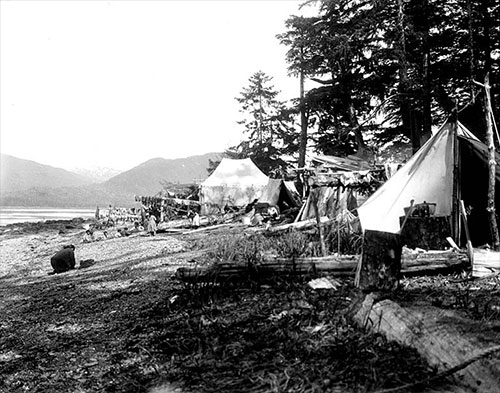

In 1962, the state undertook a failed effort to establish an elk herd near Valenar. Eight elk calves were captured on Kodiak and brought south. Unfortunately, all eight were shot by one of the homesteaders for trampling his garden. The Valenar area was also the site of Stan Hewitt's plans for a nine-hole golf course. At one point in the early 1990s, the state of Alaska looked at the northern Gravina area as a possible location for a large state prison, but eventually built one north of Anchorage instead. The northeastern end of Gravina was also a popular spot for homesteaders, most notably Jean Sallee, who lived there for decades. The state of Alaska has talked about a road to that end of the island for decades. Rosa Reef on Gravina - across from Totem Bight - was a common hazard to navigation upon which many local vessels came to grief over the years despite several navigational aides in the area. Lewis Reef and Lewis Point were other navigational challenges on the Gravina side of the Narrows, but they were also site of industrial activity first by Bill Smart and then by Steve Seley who operated a sawmill in the uplands. Just to the south is the Ketchikan International Airport was the location of the former town of Port Gravina, a small community that included a sawmill, a school and some other businesses, primarily founded by Tsimshian's from Metlakatla. ( See "The Village of Port Gravina, SITNEWS, Feb. 4, 2006) which existed from 1892 to 1904 until it was wiped out by a devastating fire and never rebuilt. In general, the land on Gravina was flatter and much more suitable to development than the land on Revillagigedo, but Ketchikan stubbornly insisted on primarily stringing itself along the Revilla shoreline. It was up to the federal government to see the use of Gravina when it decided to relocate the Annette Island airport to the northeast end of Gravina, across Tongass Narrows from Ketchikan in 1973. The story of that process and the endless debate of whether or not to "bridge" Tongass Narrows is too long to summarize here. ( See "Gravina Airport is 45 Years Old," SITNEWS, Aug. 3, 2018). South of the airport on Gravina is Clam Cove which was the site of Antone Stensland's 320-acre homestead. For many years a farm on the Stensland property provided Ketchikan with something more valuable than the gold, copper and silver that everyone was always looking for on Gravina: Fresh food. Stensland was not the first "farmer" on Gravina, F.H. Fedler had a 23-acre farm on Gravina not far from the location of Port Gravina in 1907. But after 1913, Stensland provided the First City with dairy milk, fresh chicken, eggs, cheese, buttermilk and sour cream. For many years, the Boucher family also operated a vegetable farm on Gravina that also provided fresh food to Ketchikan. Also in Clam Cove was a small shipyard and boathouse where the US Forest Service where it based its "Ranger Boat" program from the early 1920s into the 1950s. It was also used by the Civilian Conservation Corps, a Depression-era program. When the Canadian National Company steamship Prince George burned at the Ketchikan dock in 1945, ( See "The Burning of the Prince George, SITNEWS, Sept. 20, 2010) the remains were beached near Clam Cove for several years before being refloated and taken south. Finally, down the near the southeast end of Gravina is the remains of the most productive gold mine adjacent to Ketchikan, according to Roppel. Around the turn of the 20th century James Bawden ran a 40-foot shaft on what he called the Bell Mine. He then changed the name to the "Goldstream" and sold out to Charles Lane, a veteran of the California goldfields. Lane built a stamp mill on site and although he eventually sold the claim he retained ownership of the machinery. The lower grade ore returned just about $8 a ton and was sent mostly to smelted in British Columbia. In 1905, a large forest fire nearly destroyed the mine but was beaten back by sea water pumps. By 1906, there was a wharf and numerous buildings on the site and it was owned by local men Otto Miller, George Irving and Harry Brice. Eventually there would be two 100-foot-deep shafts. The mine would operate, and turn a profit, until 1913. Over the succeeding years there have been several attempts to reopen the Goldstream mine and it has changed ownership several times, but none have been successful. When the debate over the Bridge to Nowhere reached its peak in the mid 2000s, Gravina became something of national punchline when commentators noted over and over that Alaska wanted to build a $250+ million bridge to an island with fewer than 50 full-time residents. While this was technically true, it overlooked the fact that - on average - more than 300,000 people come and go from the Ketchikan International Airport each year. With the Gravina Access Project in its final stages - without a hard link - there is little likelihood that Gravina will become a larger player in the local economy as envisioned by bridge proponents. But logging and other development on the island is slowing increasing the road options for Gravina. Eventually, there will likely be public road access to North Gravina and Valenar off the existing Gravina Highway. There will also likely be access to Long Lake in the central part of the island north of Bostwick, where there are several summer cabins. Going forward, Gravina will continue to be that promise of flat, developable land for Ketchikan, just a quarter of a mile away.

On the Web:

Contact Dave at dave@sitnews.us Dave Kiffer ©2021 Publication fee required. © Representations of fact and opinions in comments posted are solely those of the individual posters and do not represent the opinions of Sitnews.

|

||||||