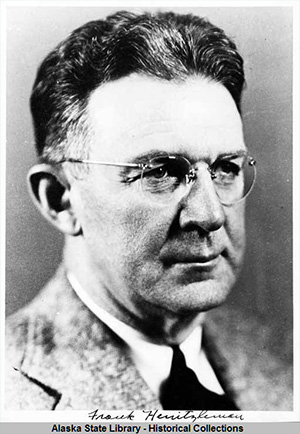

An American forester who spent much of his career supporting the development of the Alaska TerritoryBy DAVE KIFFER June 24, 2019

Heintzleman was known as a "lukewarm supporter" of statehood at a time when most of the state was strongly in favor of it. He was also an opponent of Native land claims. But, in Southeast Alaska, Heintzleman would have a greater legacy, as the main proponent of the timber industry. As a primary US Forest Service official in Alaska from the 1918 to the 1950s, Heintzleman was a constant promoter of what he hoped would be a permanent timber industry. When Heintzleman died of a heart attack in Juneau in June of 1965, the 77-year-old was called "instrumental in the construction of two huge pulp mills in Southeast Alaska," in an obituary in the New York Times. "Widely known as 'Mr. Alaska' by his colleagues in the Forestry Service, he was one of the best informed men in the territory on its history, people and resources," the Times concluded. Benjamin Franklin Heintzleman was born in Fayetteville, Pennsylvania on Dec. 3, 1888. He attended public schools there and then received his Bachelor in Forestry from Pennsylvania State College in 1907. In 1910, he received a Master of Forestry Degree from Yale University in 1910. Almost immediately, Heintzlman joined the US Forest Service and was sent out west to work in Washington and Oregon. In 1918, he was sent to Alaska to oversee a lumber production operation that harvested Sitka Spruce to be used in military airplanes during World War I. He immediately loved the possibilities of Alaska. "Everything here isn't card filed and cross indexed," The New York TImes reported he told a friend when he was sent to Alaska. "As a Pennsylvania Dutchman, I like it." From 1918 to 1934, he served as the Assistant Regional Forester, based in Ketchikan. He proved to be a strong proponent of a growing timber industry in the territory. He was also involved in several USFS studies that argued for a greater use of the region's timber resource. "Southeast Alaska is essentially a timber producing region," Heintzleman wrote in "Pulp-Timber Resources of Southeastern Alaska," a USDA pamphlet written in 1928. "There are no climatic factors which prevent or seriously hinder the operations of woodworking establishments throughout the year. The main seaways and most of the small inlets are free of ice throughout the winter, so water transportation is possible at all times. The logging season is usually considered as covering eight months, April 1 to December 1, but winter logging is practicable in many localities and some concerns are operating for periods as long as 11 months." In 1928, Heintzlman estimated that 75 percent of Southeast's commercial timber was within 2 1/2 miles of tidewater. He noted that region had at least three million acres of commercial value timber, out the 17 million acres in the Tongass National Forest. He estimated that the average acre had 25,000 board feet, while more concentrated stands had between 30,000 and 40,000 board feet. He said there was 58 billion board feet of Western Hemlock and 15 billion board feet of Sitka Spruce. There was 2 billion board feet of each Western Red Cedar and Alaska Cedar. He noted that the heavy rainfall quickly regenerated logged areas and that timber could reach commercial maturity in 85-100 years. Heintzleman's surveys focused on the commercial values of the Hemlock and Spruce. "It (Hemlock) is moderately strong, light in weight when dry, fine grained, light in color and almost odorless and tasteless," Heintzleman wrote. "It is hard enough to stand up to heavy wear, although sufficiently soft to be worked easily." He noted that it was good for flooring and other uses such as heavy timbers and inside finish. A current (1928) use was for fish traps. "Very little hemlock is being cut in Alaska because it can not profitably be shipped to the general market in competition with Puget Sound hemlock," he concluded. But the real allure of Hemlock, Heintzleman wrote, was in its use as pulp. "The high value of western hemlock in pulp and paper manufacture has been fully established by the paper mills in Washington, Oregon and British Columbia which use a greater quantity of this wood than any other species." Meanwhile, he saw the Spruce value in specialty uses, such packing cases for the salmon industry, and continued use in the aviation industry. Once again, one of the biggest challenges, he said, was competition from similar sources in the Pacific Northwest that were closer to manufactures. Timber was important for construction in Southeast Alaska from the beginning, as the small communities were literally hewn out of the rainforest. Timber was particularly crucial for docks and pilings as few areas had flat land for development. When Ketchikan Power Company - also known as Ketchikan Spruce Mill - began operation in 1903, a significant portion of its output also went into boxes for the growing canned salmon industry. By 1909, approximately six million board feet of timber was being harvested in Southeast Alaska. By 1927, Heintzlman pegged the output as close to 52 million board feet. He felt that was a fraction of what the region could produce. He noted that the 100,000 board feet a day coming out of sawmills in Ketchikan and Juneau was nearly entirely for location use, as was the 70,000 board feet being produced each day at a mill in Wrangell. "An extensive sawmill development primarily for entering the general markets is considered inadvisable," he wrote in 1928 " The pure stands of high grade spruce saw timber are too limited to support a large industry." But the potential for "pulping" the vast stands of lower grade Hemlock and Spruce was where Heintzleman saw growth. And in the area of "newsprint" rather than pulp. "The extensive forest resources of Southeastern Alaska will undoubtably be exploited chiefly for the manufacture of newsprint paper because of unusually favorable conditions there for the large scale operations that now characterize that industry," He wrote in 1928. He noted that the region could produce at least 1.5 million cords of pulpwood in perpetuity with full renewal and that would convert into 1 million tons of newsprint, roughly one quarter of the current yearly consumption in the United States. At that time, he noted, most American newsprint was supplied by mills in Canada. "The outstanding advantages of southeast Alaska as a location for manufacturing newsprint are water transportation to the markets of the world and abundant water power and timber resources which are a available for bona fide development and use under reasonable agreement with the United States," He wrote. "These advantages are sufficient to assure the establishment of a large, permanent paper-making industry in the region." In 1934, during the Great Depression, Heintzleman was made head of the National Recovery Administration forest conservation program. Then in 1937, he was made the Alaskan representative of the Federal Power Commission, where he worked to promote hydroelectric development in the territory as a ready power source for the large pulp mills he still envisioned in the region. In 1937, he was also named Alaska Regional Forester for the USFS, a position he would hold until 1953. During that time, he also served on the Alaska Territorial Planning Board where he continued to advocate for an expanded timber industry in Southeast Alaska, particularly as overfishing was now causing the salmon canning industry to decline. A history of the Forest Service in Alaska on the USFS Alaska website called Heintzleman an "interesting and complex individual." "A builder and dreamer, his major interest was to recruit capital and big industry for Alaska, for without capital the region could not develop," the website history notes. " Much of his time was spent in the states attempting to interest outside capital to invest in lumbering and power development. A political conservative, he was liked and trusted by the business community. From a purely technical standpoint, he was not an outstanding administrator. He was hard on the men, expecting a full day's work and more for each workday. He was slow to give raises in pay and reluctant to give transfers. Soft-spoken and modest in manners, he liked to deal with men in individual meetings rather than in group conferences...however, he fought like a lion for his fellow workers in the face of unjustified criticism. He was a visionary, anxious to move ahead and impatient of details in planning." The Forest Service history also noted that Heintzleman frequently clashed with people who did not share his "vision" for Alaskam such as higher ranking Forest Service officials and even the politically powerful Secretary of the Interior Harold Ickes. Ickes specifically clashed with Heintzleman and other Forest Service officials over the issue of "possessory rights" whether or not the Natives of Alaska should have control over sections of their traditional homelands in Alaska. Ickes felt that the Natives should have some control through variations on the "reservation" system in place in the Lower 48 and on Annette Island in Southeast. "The judgments of the Department of the Interior were alarming to the Forest Service," The Forest Service writes in its history website. " If Ickes's views were realized, the whole timber industry in southeastern Alaska would be jeopardized. Pulp companies would be discouraged from making investments, since the right of the Forest Service to make timber sales would be in doubt. Heintzleman expounded his views in a letter to Harold Lutz. The effort to give Indians title to southeastern Alaska, he wrote, was 'under the theory that they are the owners of all the lands and resources through their heredity of aboriginal rights and that these rights have never been extinguished by the federal government.' Heintzleman blamed the Department of the Interior for the matter, particularly Secretary Ickes. 'With the assistance of the Interior Department, and on the basis of some legal opinion given by the Secretary of the Interior by the Solicitor's office of that department,' he wrote, 'each village, as S. E. Alaska has never had a tribal organization, has made application for hundreds of thousands of acres of land and tidewater fishing areas that blanket all the fishing sites and large areas of trolling grounds." He went on to summarize the existing laws under which the Indians could acquire land. He concluded, 'The thought is often expressed by private citizens that the move to set up vast Indian reservations in S. E. Alaska is based, in large part, on a desire to eliminate the National Forests in Alaska.' In her 2016 book on Southeast land claims, "The Drive to Civilization," historian Diane Purvis writes that Heintzleman was essentially a "spokesman" for the pulp timber industry. "His motivations were crystal clear," she wrote. "The Tongass was the greatest reserve in the nation for this commodity. That the same land might be also in dispute was unexpressed." It would take federal legislation in 1947, an a law suit that wound it's way all the way to the US Supreme Court, to at least partially resolve the issue, which wasn't completely addressed until the Alaska Lands Claims Legislation in 1971. Meanwhile, as regional forester, Heintzleman continued to push projects to promote a larger timber industry for the region. One of the major projects that Heintzleman worked on was the "Alaska Spruce Log Program" which began in 1942. The ASLP mirrored the program that Heintzlman originally came to Alaska for back in 1918. It provided mills in the Lower 48 with high grade Sitka Spruce logs from the Tongass. Most the spruce was intended for airplanes for the war effort. "At time, Tongass logging occurred primarily by hand-felling trees the best trees in accessible sites, such as the beach fringes and river bottoms," University of Alaska-Fairbanks researcher Colin Beier wrote in 2009 in "Growth and Collapse of the Resource System: An Adaptive Cycle of Change in Public Lands Governance and Forest Management in Alaska." "However the collective opinion of Tongass managers, many of whom were professionally trained foresters, was that clearcutting was a far superior method. (An article in 1935) in Ecology provided scientific justification for the change from high grading to clearcutting in the Alaskan rainforest. With this justification Tongass managers shifted the silvicultural prescription to clearcutting and sought to demonstrate the economic viability of harvesting the low grade timber that comprised the majority of the Tongass timber base." In 18 months of operation, the ASLP operation did just that, exporting 38.5 million board feet of high grade spruce to the mill and 46 million board feet of low grade material to local Alaskan mills. "Although short lived, the wartime program demonstrated the commercial viability of both saw timber and utility grade materials from the Tongass," Beier wrote in 2009. "It also forged strong relationships among Tongass officials, national policy makers and timber-industry representatives." After the war, Heintzlman was heavily involved in the creation of the Tongass Timber Act of 1947. It was the first effort of the Federal Government to actively promote an industrial, regional timber industry in Southeast Alaska. It was this legislation that would eventually lead to the longterm contracts in 1951 and 1953 that would lead to the creation of large pulp mills in Ketchikan and Sitka. But even after the Tongass Timber Act in 1947, Heintzleman was still acting as the leading promoter of the nascent timber industry. In 1949, he made Alaska's case for an expanded timber industry in "Forests of Alaska" in the United States Department of Agriculture's 1949 Yearbook. "Sitka Spruce is generally conceded to be the best pulping wood on the Pacific Coast," he wrote in 1949. "The best of the Alaskan forests is found in Southeast Alaska. Most of the timber is more suitable for pulp than (other) uses. The economy of the Southcoast region, with approximately 35,000 inhabitants, is now based largely on the commercial sea fisheries but lumber production, now approaching 100 million board feet annually, is growing in importance. When fully developed the timber industries, including especially pulp manufacture, will equal and may even exceed the fisheries in value of yearly output." Drawing on his experience with the Federal Power Commission, he extolled the power potential in the rainforest. "The heavy rainfall and the availability of of many high mountain lakes for storage reservoirs give this section good water power sources," he wrote in 1949. "Detailed studies show that approximately 200 of the better undeveloped power sites have a total yearlong capacity of 800 thousand horsepower." He noted that there was 78,500 million (78.5 billion) board feet of timber in the Tongass, enough to permit the cutting of 1 billion board feet a year in perpetuity, given that the clear-cut stands would reach commercial size in 80-85 years. He promoted the idea that clear-cutting was the most efficient, cost effective, and economically friendly way to proceed in Alaskan forests, primarily because of the shallow root systems that cause trees to blow down in areas that were more selectively cut. "Consequently, the forest manager has to clear cut the forest and, to ensure natural reseeding, leave seed trees in the form of large patches of undisturbed timber spotted over the cutting area," Heintzleman wrote in 1949. "Selective cutting is also impracticable on most areas here from a logging standpoint. Because of the large size of the timber, the dense brush, and moist soils, powerful donkey engines and heavy wire cables must be used to pull the logs from the woods and if individual trees were left standing throughout the logging the area they could not be protected from destruction or injury by the logging equipment and machinery." Heintzlman also continued the promote the idea that a fully functioning pulp export industry could rescue the region from the doldrums as the salmon canning industry continued its downtown. "If fully developed, the (pulp/paper) industry could support, directly and indirectly, a total of 30,000 persons in Southeastern Alaska," he wrote. "Pulp manufacturers would have the obviously great advantange here of being able to obtain an assured supply of timber for a long term of years," "Other favorable features include low logging costs because of the ready accessibility of the timber stands to tidewater, cheap log towing to mills along the protected seaways, a mild winter climate and ocean transportation from the mills to the general market." In 1954, the first large mill opened in Ketchikan and was soon followed by one in Sitka. But by then, Heintzleman had a new portfolio. In 1953, he was appointed Alaska Territorial Governor by President Dwight Eisenhower. When the Ketchikan mill opened, now Gov. Heintzleman proclaimed "hereafter in Alaska the 14th day of July will be celebrated as the anniversary of one of the most important events in the Territory's history - the dedication of Ketchikan Pulp Co. This is not only the first plant of its kind in Alaska but also represents the largest single industrial investment ever made here. It is an important milestone in Alaska's road to full industrial development." As govenor, Heintzleman continued to promote development of Alaska's federal land, but he almost immediately waded into the most controversial topic of the time, Alaska Statehood. Although his predecessor, Ernest Gruening had been a very strong supporter of statehood during his term from 1939 to 1953, Heintzleman was best described, by a 1954 article in the Ketchikan Chronicle, as "lukewarm" in his support of statehood. Like many officials in the state, he questioned whether Alaska had the population and the economic strength to support itself. In 1954, he wrote to Joseph Martin, the Speaker of the US House of Representatives, and suggested that only the "developed" part of Alaska be granted statehood. Heintzleman suggested two Alaskas. A state that included Southeast and the Railbelt, with the rest of the state remaining a "territory." The negative reaction was swift as several hundred Alaskans petitioned President to replace Heintzleman with someone who supported statehood for the entire state. Heintzleman quickly changed course and announced his full support for Alaskan statehood. In 1956, he signed the legislation establishing the Alaska Constitutional Convention which would lead to statehood in 1959. Heintzleman also ran afoul of the growing Native Land Claims movement, primarily because he was concerned about development and believed that Native Land Claims would make it more difficult. He specifically opposed the Native claim of "possessory rights" to millions of acres of Alaska. His opposition put the state in a lengthy legal battle in the United States Court of Claims that was appealed to the US Supreme Court. The courts ruled in favor of the federal government. In December of 1956, Heintzleman resigned the governorship, noting that he had completed "46 years of public service" and wanted to "retire to less strenuous work." He retired in January. His work after retirement included service on the University of Alaska Board of Regents and the Alaska Rail and Highway Commision. In 1959, he was named Juneau Man of the Year and the state Chamber of Commerce name him citizen of the year. In 1964, he was with a friend out in the Mendenhall Valley and the friend asked him if there was anything he thought should be named after him. Heintzleman pointed at the mountains between Lemon Creek and the Valley. "That ridge," he replied. He died in 1965 and in 1966, the eight-mile ridgeline was named Heintzleman Ridge.

On the Web:

Contact Dave at dave@sitnews.us Dave Kiffer ©2019 Publication fee required. © Representations of fact and opinions in comments posted are solely those of the individual posters and do not represent the opinions of Sitnews.

|

|||