The First City in 1898, before it was a cityVisitor from Tacoma wrote it was his idea to move the customs house to KetchikanBy DAVE KIFFER October 24, 2021

But when James Bashford arrived in January of 1898, that was all in the future. In 1948, Bashford shared his memories of Ketchikan in 1898 with the readers of the Alaska Sportsman Magazine in a story called "Frontier Town."

It is an interesting view of the First City just as it was transitioning into the first port of call in Alaska. And, if you take Bashford's word for it, he was at least partly responsible for Ketchikan becoming the main city in Southern Southeast Alaska. While some of the information in "Frontier Town" is questionable (Bashford claims to have met notorious Skagway con man Soapy Smith on the voyage up) or just incorrect (that Mrs. N.G. House was the only "white woman in Ketchikan") there remains more than enough "local color" about the community to give a snapshot of Ketchikan right at the point where it was becoming "Ketchikan." Bashford arrived from Seattle on the S.S. City of Seattle, a ship owned by the Washington and Alaska Steamship Company. In his story, Bashford said there were 800 people on board the ship which would have been significantly above its normal passenger load of 600, but during the Klondike Gold Rush, which began in 1897, it was not unusual for ships to cram large numbers of gold seekers into every nook and cranny for the voyage north from Seattle.

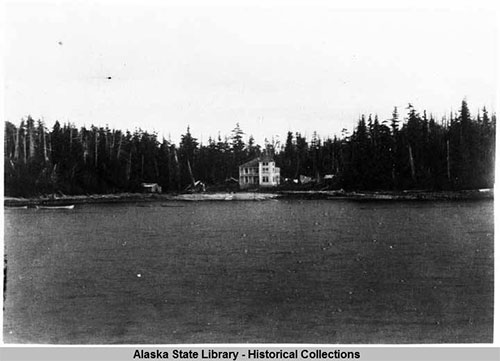

Since nearly all the passengers were headed for the Klondike, it is not surprising that Bashford was the "only passenger bound for Ketchikan." He noted that the January weather had been rough on the way up and that a "lad from Montreal was killed in Queen Charlotte Sound when he was swinging on some ropes and a masthead light fell on him." "It was about eight o’clock in the evening when the ship stopped off Ketchikan and I heard the first howls of the dogs at Indiantown," Bashford wrote. "I was put ashore in a small boat with a couple of sailors who could not row. I gave a hand at the oars. We brought up on the rocks near the old saltery dock. My being in Ketchikan was the result of an uncle’s grubstaking Mr. and Mrs. N. G. House, an elderly couple and old friends from Tacoma, in some mining activities."

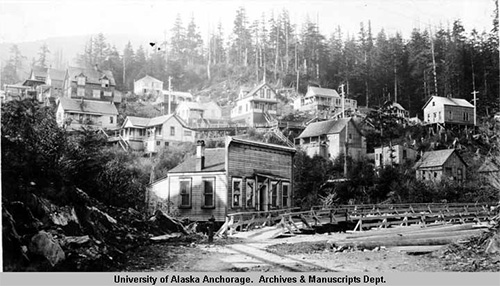

He wrote that Mr. and Mrs. Houses lived in a "two room shanty" a block north of the saltery dock facing "Gravina Island." (more likely Pennock). "Between the house and the dock was the Indian 'guest house,' standing on a promontory which gave a fine view up and down Tongass Narrows," he wrote. "George Grant’s home was a short distance behind ours, and just beyond lived the partners, Gingrass and McTaggart. Next was the shanty of Harry and Otto Inman. A Japanese fisherman called Harry, I believe, had a cottage just beyond the Inman boys’ cabin on the beach." Bashford wrote that Martin and Clark's general store was located several hundred feet behind the saltery. "It was more than a store," he wrote. "It was a meeting place for Indians and whites, and a hangout for halibut fishermen when they were in port. Two of the halibut boats I remember were the Shamrock and the Jennie F. Decker." Ketchikan was full of "entrepreneurial" spirits at the time and Bashford was immediate drawn into the empire building.

"George Baker claimed to have the water rights on Ketchikan Creek," Bashford wrote. "He offered me an interest in the power rights on the creek if I could get someone to put in an electrical plant. I got in touch with several persons in Tacoma in an effort to get a lighting plant, but they 'could not see the light' in a little village hanging on the rocks of the Alaska coast." Bashford also became acquainted with Orlando W. Grant, one of more prominent local citizens, a miner and businessman who soon became the deputy marshal for the community. "Grant was a booster for Ketchikan," Bashford wrote. "Several weeks after I had arrived, he was asking me what I thought might bring more people to Ketchikan. We were standing in the old Indian guest house at the time. I told him I thought that if the customs house could be transferred from Mary Island to Ketchikan, all the steamers would stop and it would help the town grow. If the Bureau of Customs were offered a location for its officers’ quarters, or some such inducement, Ketchikan might get the office. Grant said that he would give the necessary land, and I understand that later he did make such a proposition to Uncle Sam, and he built the custom house."

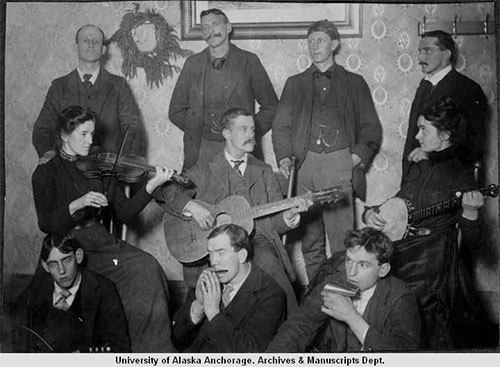

Bashford noted that with few women in town, social activities were limited but that Ott Inman held dances at his home. "They took place when the halibut fishermen were in. To make up for the lack of women, some of the boys extracted their shirt tails and became girls for the evening. The orchestra was made up of several fiddles, with the Campbell boys performing. 'Uncle Than' House sat in the center of the room on a nail keg and played the bones, while another artist swept a broom handle across the floor in a fine imitation of a bass viol." Shortly after he arrived, Bashford wrote, there was a heavy snowfall and he remembered Mike Martin, soon to be Ketchikan's first mayor, organizing a "trail breaking crew" to clear the snow off the boardwalks, all the while carrying a "large oriental parasol" to keep the falling snow off his head. A big issue in those days was what do with "stowaways," people who had snuck onto northbound steamships without paying and were then put ashore when the ships reached Alaska. Many were dropped off at Mary Island - which was still the entry point until 1902 - but then the customs workers would send them on to Ketchikan.

"No one (here) wanted them...so a number of citizens agreed to meet the steamers and suggest to the ship masters that their unwanted cargo be taken farther north," Bashford wrote. "The Utopia was one of the first steamers to run into our stowaway ban. Captain White was determined to put his man on the beach. He failed at the dock but made another attempt by means of a small boat a quarter of a mile above town. Our committee met the boat. There followed an argument, in the midst of which the stranger broke out in a voice laden with tears. “What am I to do? They won’t take me on the ship and you won’t let me ashore. What the hell am I to do?” Bashford said the man was put ashore on Gravina (most likely Pennock) but eventually made his way to Ketchikan, where he got on another ship heading north. Bashford said he met the "stowaway" several weeks later, returning from up north where he had clearly done well for himself. Bashford wrote that he joined the House couple in some prospecting efforts, most notably up the Unuk River. "Mrs. House, who claimed to have 'second sight,' could see rich ore deposits in this vicinity, but the only deposits we found were of ice and snow," Bashford wrote. "There were the usual 'lost mine' yarns. One concerned a large gold-seamed boulder on the beach at Helm Bay. Later we bought George Baker’s sloop and made a trip to Helm Bay to investigate. We failed to find a trace of gold-bearing rock, but we were caught in a southerly blow and nearly lost our ship." Bashford had boat engineer experience and left Ketchikan to go south in the spring of 1898 to study to be a ship master. When he returned to Ketchikan several months later (in early 1899), the town had changed significantly.

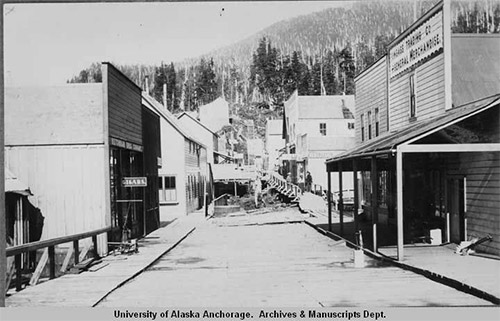

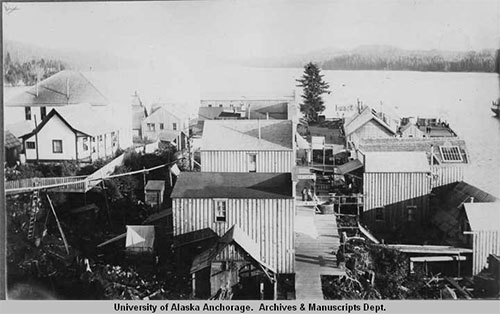

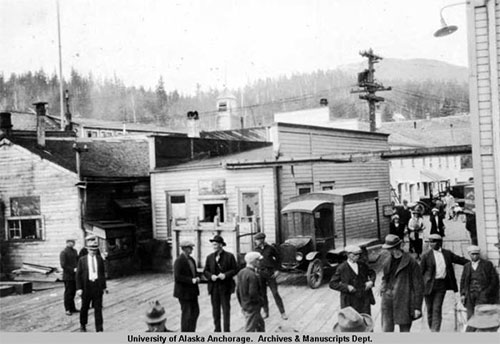

"I didn’t know the old town! It had changed entirely. There were new buildings extending from below the old saltery dock northward to what was called Newtown. My Ketchikan was gone." Bashford became the "master" of a schooner called the Atlanta. The crew worked for several months for the owner, a Dr. Shedd, who had once been a Methodist minister. When Shedd refused to pay them, they mutinied and took Shedd to Metlakatla where he got the money to pay them from Father William Duncan, who was an old friend. Meanwhile, Ketchikan continued to grow, "New houses, new faces, new business enterprises. One day Mr. House came in with the news that Forest J. Hunt, whose brothers we had known in Tacoma, had opened a little place to sell meat and vegetables. Forest Hunt had at one time been County Commissioner of Pierce County and had later been located at Wrangell. His business was conducted in a tent at first. Later he moved into a building near the site of the old guest house, which was now gone." Through it all, Bashford wrote that he associated with all levels of Ketchikan society, even the "lower strata." He noted that in those days much of the sporting activity took place in Newtown, specifically Hopkins Alley. "On the list of characters were Silver Tip, Dutch Liz, Timberline, and one whom the boys called 'Pretty Lady.' She was indeed pretty and rather refined, and her past was the subject of much comment among the men and women of town. Liquor came in cases usually labeled 'Nervine' or 'Wheat Phosphates.' The Farallon usually had some. When her chime whistles started down below Saxman the dogs would howl and (people) would yell, 'Steamboat a comin’!' and there’d be a rush for the ship’s bar."

Unfortunately, the arrival of a new shipment of booze often led to trouble. Bashford remembered a specific incident in which a fisherman named Dan Robinson got liquored up and began trying to shoot the town up with his rifle. The gunplay ended when a "Marshal" - unnamed by Bashford - shot and killed Robinson after Robinson tried to shoot someone near the Owl Restaurant. Bashford said the marshal was transferred to Valdez after he was threatened by several friends of Robinson. Robinson's remains were sent to Pennock Island, one of the first graves in the new community graveyard. Bashford wrote that he had planned to stay in Ketchikan but that the House family mining ventures were unsuccessful. Bashford was hired to take a boat to Seattle. "The buildings of Ketchikan and Saxman and the shores of Tongass Narrows faded as we headed south-ward," Bashford wrote in 1948. "But I was going to see them again soon. I intended to bring my mother and return immediately. My return to Ketchikan was postponed for a few days, then a few months, then years. I’m still hoping to go back." After he left Ketchikan, Bashford had a long career in the Pacific Northwest as a professional photographer. He gained a measure of fame by taking photographs of the collapse of the Tacoma Narrows bridge in 1940. He died in Tacoma in 1949 at the age of 72.

On the Web:

Contact Dave at dave@sitnews.us Dave Kiffer ©2021 Publication fee required. © Representations of fact and opinions in comments posted are solely those of the individual posters and do not represent the opinions of Sitnews.

|

||||||||||||