KETCHIKAN PULP MILL

CLOSED 20 YEARS AGO

By DAVE KIFFER

March 22, 2017

Wednesday PM

Ketchikan, Alaska - Twenty years ago this week, the hammer fell on the community of Ketchikan.

On March 25, 1997, Louisiana Pacific announced the closure of the Ketchikan Pulp Mill, the primary engine of the Ketchikan economy for more than 40 years. The final bale of pulp - which is now on display at the Southeast Alaska Discovery Center - rolled off the production line that same day.

The announcement was not a complete surprise, given the fact that the financial and political realities of operating a large pulp mill in the Tongass National Forest had changed dramatically in the 1980s and 1990s. Louisiana Pacific itself had estimated that it would take more than $200 million in upgrades to bring the nearly half-century-old facility up to current production and environmental standards.

But, for a community that had hummed year round for decades on the strength of the timber industry, the closure announcement was a shock to the system.

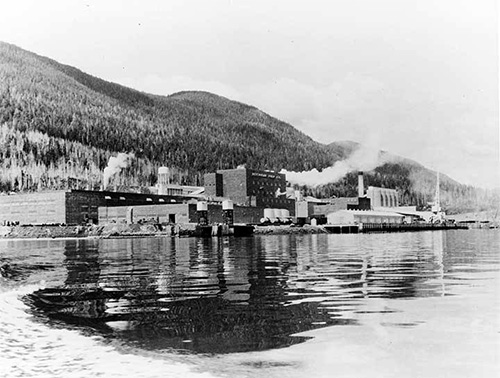

View of Ketchikan Pulp Co. mill from the water.

Date unknown.

Photo courtesy United States Forest Service Photograph Collection

The closure immediately cost the community 514 year-round jobs and caused a ripple effect that was estimated at least 500 other direct jobs lost. Untold other job losses occurred as retail sales dropped across the spectrum. One of the local shipping companies estimated its revenues dropped 20 percent in the first month. Ketchikan's housing market flooded and prices dropped accordingly.

When many of the former millworkers, and their families, left the community to find jobs elsewhere the population dipped, from a high of nearly 15,000 in the mid 1990s, to just about 13,000 in 2003. Local schools were hit harder when the number of school children decreased by 25 percent.

But even these drops were not as big as had once been predicted. State surveys taken in the late 1980s had estimated that Ketchikan would lose more than 35 percent of its population and half of its school population if the timber industry collapsed. By the time the end came in 1997, the industry had already been retrenching for nearly a decade and therefore the blow wasn't as hard as it could have been.

In announcing the closure, LP also reached an agreement with the federal government over long-standing timber supply issues. As part of that agreement, the company received $147 million and the right to an additional 300 million board feet of timber for its two remaining sawmills in the region. It was thought, at the time, that the sawmills could keep the timber industry alive long enough for another long term timber harvesting plan to be developed, but by the time that plan - which involved switching from old growth timber to areas that had already been logged and had grown back - was developed, more than 15 years had passed.

There was also another industry, tourism, that was growing rapidly and would quickly replace timber as the town's major industry, although many of the tourism jobs would be seasonal rather than year-round like the pulp mill related jobs. In a sense, although Ketchikan's overall economy eventually rebounded, it was now more seasonal, as in the pre-timber past, when mining and fishing were the major industries. In 1996, slightly more than 300,000 cruise visitors came to Ketchikan between April and October. In 2017, that number will top 1 million.

Although the timing of the mill closure caught some in the community by surprise, there had been local efforts including the ill-fated "2004" effort to get the community talking about what it would look like if Louisiana Pacific didn't get a renewal of its 50 year timber contract and closed the mill. Unfortunately, that "2004" process came to naught when the Ketchikan Gateway Borough Assembly decided to prematurely end the process before recommendations could be made.

When the Alaska Pulp Corporation closed its pulp mill in Sitka in 1994, it was clear that the clock was ticking against the industry. US. Senator Ted Stevens pushed the US Forest Service to begin work on an extension of the Ketchikan Pulp contract and when that didn't happen, Stevens, then head of the powerful Senate Appropriations Committee arranged for a payment of $110 million to go to Alaska to help offset the economic losses in Southeast. Approximately $30 million was to go to specific industry related measures while $70 million would be distributed between the communities most effected by industry closures, Sitka, Wrangell (which hosted a large sawmill) and Ketchikan.

Originally, the federal government - through the Department of Agriculture - planned to set up a grant program that would take requests from the communities and then decide which ones to fund. But the Ketchikan Gateway Borough sued the federal government, demanding that the money be released directly to the communities, as directed by the Steven's legislation.

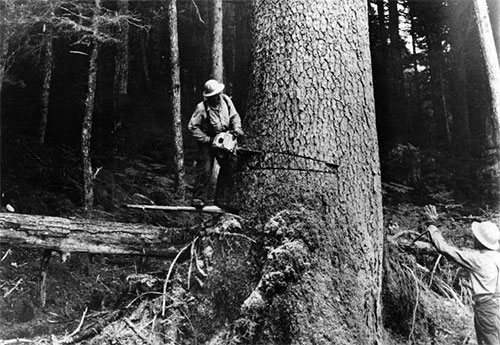

Loggers, harvesting a large tree. Southeast Alaska.

Two loggers, including one on spring board, cut a wedge into side of tree with a chain saw. Date unknown.

Photo courtesy United States Forest Service Photograph Collection

The federal government settled the case and the money went directly to the communities, meaning that the Borough received $25 million of the Steven's appropriation. The Borough would use that money on a variety of fronts, raising significant community controversy doing so.

In 2001, the State Department of Labor statistics took a survey over the four years following the mill closure. It found that overall, Ketchikan had lost more than 1,000 jobs because of the closure and that three quarters of the people losing those jobs moved elsewhere with around 250 of the workers remaining in Ketchikan. The DOL found that that the economy of the community had shifted from production to services but that even before the closure government was largest employer in the community. According to the DOL, a list of the top ten employers in the community in 1994 found that six of the ten were government related. In 2000, nine of the top ten were government related. More recently, in 2015, eight of the top ten largest employers in Ketchikan were government related.

Wages dropped significantly, around 12 percent, community wide after the mill closure, according to the DOL. And the percentage of workers working more than one job increased from five percent to more than 15 percent. The percentage of laid off mill workers working more than one job was nearly 30 percent in 2001. When the mill closed in 1997, most of the workers were laid off within two months. Severances varied but most long term employees received around 12 months of severance pay. The DOL determined that about half of the laid off workers did not immediately begin to search to work but that 80 percent of those that remained in Ketchikan had found new employment within 16 months of the closure.

After LP announced the closure, it began the process of demobilizing the mill and cleaning up the area. This also became a controversial process. The Ketchikan Gateway Borough took the position that it wanted to "preserve" as much of the local timber industry as possible and therefore was not interested in a full remediation of the mill property. The Borough supported remediating the site to "industrial" development standards. As a result when the demobilization of the Ward Cove property was generally completed by 1999, the community did not have a fully remediated site in the same manner that APC had left the Sitka mill property a generally blank slate for future development.

Pond men on floating logs, Ketchikan Pulp Mill.

Date unknown.

Photo courtesy United States Forest Service Photograph Collection

Years later, some borough officials would concede that efforts to redevelop the Ward Cove property were significantly delayed by ongoing remediation that could have resolved earlier in the process.

How the $25 million in Steven's money was used was also very controversial.

Initially, the Borough set aside $987,000 for an Anchorage based public relations firm to promote the timber industry, as the Borough continued to believe that revitalizing the industry should be its main goal. That was money was also to be used to promote the community as a place to relocate businesses.

Just about $500,000 was spent on continued legal battles with the federal government to force it to continue to provide the timber harvest availability in the Tongass National Forest even though the long term contracts were no longer in force. An additional $150,000 was spent suing the federal government for "damages" arising from the mill closure and the invalidating of the long term contract. Neither effort was successful.

The Borough also had to deal with a variety of proposals that sought money from the Steven's fund in order to develop industry in the community. The most notorious was a plan to build wooden bowls that ended up costing the Borough more than $300,000. Other plans called for light aircraft manufacturing or space and funding develop magnetic levitation technology for the US Navy. None came to fruition.

At one point, the Borough tried to set up an economic development fund that could vet the various proposals, but that proved too burdensome to entrepreneurs who found it easier to just go directly to the Borough Assembly with their proposals.

Meanwhile, as LP continued to demo the site, there were efforts to come up with a large tenant for the Ward Cove property. Sealaska and LP looked into the possibility of a joint veneer mill and there was also discussion about a medium density fiberboard plant as well.

Representatives of LP contacted the Borough in 1998 about a possible "loan" from the Stevens fund to explore the veneer mill option and both side began working out a possible deal. The Borough was then surprised when in the spring of 1999, LP's interest in a veneer plant "loan" disappeared and new corporation - made up of several former KPC executives - called Gateway Forest Products came into the picture.

The Borough went ahead and provided a $7 million loan to GFP for a veneer plant, which the company then constructed, but filed for bankruptcy within two years, contending that there wasn't enough "timber supply" to keep it operating. During that bankruptcy reorganization process, the Borough extended an additional loan of $2.5 million to the company - with the mill site as collateral. But the Borough was not in what was called "first position" for the mill buildings and equipment.

When Gateway Forest Products finally gave up reorganization efforts, the Borough found that if it wanted to retain the veneer mill for possible future operations, it had to buy out Wells Fargo's $2.5 million interest in the building and equipment, which it did.

Skyline logging by Ketchikan Pulp Co. in Neets Bay, August 8, 1957.

Photo courtesy United States Forest Service Photograph Collection

The Borough also chose to "make whole" a handful of local businesses that were still owed money by GFP. A large portion of that $5 million went to Southcoast Construction, a major local employer which itself then went out of business.

All told, about $17 million of the Stevens money was spent on efforts to keep either LP or GFP in Ward Cove. The Borough estimates that it eventually got back $12 million when it sold off portions of Ward Cove.

Bankruptcy proceedings involving Ward Cove went on until late 2004. The Borough also sued Louisiana Pacific which resulted in an agreement in which LP returned to the site made additional clean up efforts.

The Borough then began looking for a company willing to operate the veneer mill and Renaissance Ketchikan Group was chosen. The company actually got the mill running between 2006 and 2008, but then ran out timber supply and declared bankruptcy. The veneer mill equipment was sold off.

In the meantime, the Borough had made significant inroads with the state government by encouraging the Alaska Marine Highway to relocate its administrative offices to the Ward Cove. Governor Frank Murkowski, a former Ketchikan resident, moved the AMHS administration to Ketchikan, where it remains today. After the veneer mill closed down, the AMHS also purchased the plant site for $2.5 million and began development of a layup and engineering facility at the head of the cove.

In 2011, the remainder of the mill site was sold to David Spokely for $2.1 million, ending twelve years of Borough financial involvement in the mill site. Spokely uses the site primarily as a base for his operations to supply outlying industrial activities around the region.

Meanwhile, the community economy slowly began to rebound from the mill closure with the tourism industry rapidly increasing until 2008 when a world wide recession halted its growth. But by 2010 tourism growing again and the state Department of Labor estimated in 2014 that the Ketchikan economy had fully regained the level of activity it had prior to 1997. The town area population had mostly rebounded, to just under 14,000 in 2016. But the population of school students was still nearly 25 percent below its peak in the early 1990s.

Ward's Cove, Ketchikan, before the mill - Circa 1932-1959

"A $40 million pulp mill, which will produce 550 tons of high grade dissolving pulp daily will rise during 1952 at this site on Ward's Cove near Ketchikan."

Photo courtesy Alaska State Library - Historical Collections

In 2017, the Ketchikan economy remains multifaceted with fishing, health care and regional service industries each making up a major share. The tourism industry occupies the "big dog" status that belonged to the timber industry between 1954 and 1997.

Timber harvests still take place on private land in the region, but the era of "big timber" has clearly passed in the Tongass National Forest. Pulp production in other areas has also waned as large pulp mills in Prince Rupert and Washington state closed. By 2002, Louisiana Pacific was completely out of the pulp business.

The timber industry, which a territorial survey in the 1920s estimated would last "indefinitely" because of its renewable nature, lasted just over two generations.

On the Web:

Columns by Dave Kiffer

Historical Feature Stories by Dave Kiffer

Dave Kiffer is a freelance

writer living in Ketchikan, Alaska.

Contact Dave at dave@sitnews.us

Dave Kiffer ©2017

Representations of fact and opinions in comments posted are solely those of the individual posters and do not represent the opinions of Sitnews.

E-mail your news &

photos to editor@sitnews.us

Publish A Letter in SitNews Read Letters/Opinions

Contact the Editor

SitNews ©2017

Stories In The News

Ketchikan, Alaska

|

Articles &

photographs that appear in SitNews may be protected by copyright

and may not be reprinted without written permission from and

payment of any required fees to the proper sources.

|

|