Seeking a Road to SomewhereFor nearly a century, Ketchikan has Yearned for a way to drive off the islandBy DAVE KIFFER January 23, 2021

To be sure, even if there was a road it would be at least a 1,500-mile trip to drive from Ketchikan to Seattle but that's the not the point. You could do it, even if it took several days. It was during the expansion of the canned salmon industry in the 1920s and early 1930s, that the federal government began considering "connecting" Alaska to the rest of the country. Thomas MacDonald, who would run the Bureau of Public Roads from 1919 to 1953, first proposed a "coastal" highway between Seattle and Southeast Alaska in 1925. The Bureau studied the idea but a brief survey determined that crossing so many bodies of water along the coast would necessitate between 130 and 150 bridges, some of a size that hadn't yet been built. There was also the complication that most of the route would be through British Columbia. At the time, the Canadians were not interested in the development of a coastal road as the Grand Trunk Pacific Railroad had only reached Prince Rupert a few years before and Canada had little need to access what was the generally empty coast north of Vancouver Island. But MacDonald would not let the idea go and began looking at the possibility of a more inland route that would go north from Prince George and connect with northern Alaska. Southeast would not be left out. The preferred route, as far as MacDonald was concerned, would be through the Cassiar area in the headwaters of the Stikine River and would allow for a spur road to go down the Stikine connect Wrangell, Petersburg and eventually Ketchikan and Juneau as well.

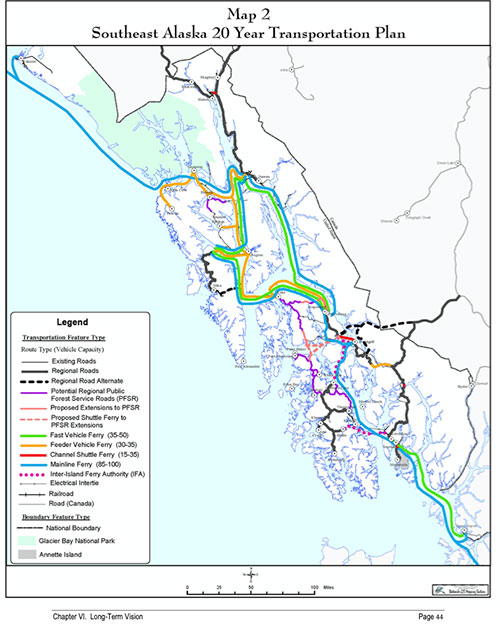

Once again, the Canadians were less than enthusiastic, feeling that the cost to connect the Yukon would not be worth it. But then in 1929, Canada suggested an inland route between the two countries to boost tourism and economic development. Then the Great Depression hit and the feasibility and expense of such a road came into question. President Herbert Hoover appointed a commission to consider the link. The board concluded the project could be built for just under $15 million dollars ($256 million in 2020 dollars) and suggested the US contribute $2 million to the project. The Canadians were looking for a larger American investment and the proposal died. Then MacDonald gained a very important ally in his efforts to link Alaska with the rest of the continent by road: The United State Military. By the mid 1930s, it was clear that Alaska was becoming a crucial regional bulwark against militarism in both Japan and the Soviet Union. Were the US to go to war against Japan, officials believed, that Alaska could be an important battle ground and having to supply the territory by sea would leave it open to a possible naval blockade. But, yet again, the Canadians balked. The Canadian leadership at the time was concerned about being drawn into a Pacific War and was worried that allowing the US to supply Alaska via Canadian territory would compromise any attempts at Canadian neutrality should war break out. Still, the United States continued to press for the road and President Franklin Roosevelt privately and then publicly advocated for the road in a speech in Chataqua, New York in 1937. Of course, this all became academic when the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor in 1941 and the US joined the war that Canada was already involved in as part of the British Empire. During the war, the 1,300-mile Alaskan highway was built between British Columbia and Northern Alaska in less than a year. The United States covered half of the $30 million cost of the road. Interestingly enough, even with the road in place more than 90 percent of the war material that was shipped to Alaska in World War II still came by ship and not the new highway. During the war, Southeast also got its first "access" when a spur line connected Haines Junction on the Alaska Highway with Haines on Lynn Canal. The road was built to allow a second military shipping option to the White Pass Railway in Skagway in case the Japanese attempted to take out the railroad. A road through the White Pass to Skagway was originally started in the 1950s but was not completed until the Klondike Highway reached Skagway in 1979. A third Southeast access point opened up at Hyder in Portland Canal on the Canadian border when Canadian Highway 37 was extended into neighboring Stewart, BC in 1984. Highway 37 - which goes from north of Terrace into the Yukon Territory - mirrors the route that MacDonald had wanted to open up in the early 1930s through the Cassiar area. When Hiqhway 37 opened in the 1980s it also spurred interest in Southern Southeast Alaska. Maybe it would be possible to run a road up one of the Alaskan river valleys and connect with the Canadian highway? Wrangell, Petersburg and Ketchikan would be on the road system after all. Roads up the valleys of the Stikine and Unuk rivers had been tried in the early part of the 20th Century, mostly by mining interests trying to better access the interior gold fields on the Canadian side of the border. But nothing permanent had been built. Ketchikan miner James Hart had built a very early trail/pioneer road up the Unuk in 1901 to access his claims on the Sulpherets River off the Unuk. The Ketchikan-based Daly family then built a larger pioneer road up the Unuk in 1911, also to access mining claims inland. Two decades later, mining engineer Arthur Skellhorne told the Ketchikan Chronicle in 1931 that he had travelled the length of the Unuk and the Iskut rivers and felt that a road could easily be built up those basins and into Canada. He noted that it would also be possible to build a road up the Chickamin River, but that it would be more difficult than a Unuk route. Skellhorne also noted that a road into the up the Unuk would follow a pioneer road built around 1910 and would access valuable mining claims on both sides of the border. The biggest challenge, Skellhorne said, was building a road to the back side of Revillagigedo and then establishing a ferry across Behm Canal to the Unuk. In 1936, the Chronicle reported that work had begun on a new road up the Unuk and that 15 miles had been cleared for a road right-a-way. "Brig" Young of the Territorial Highway Department had a crew on the river and was putting the road in. The entire road was expected to be about 72 miles long and was following the path of trails and other aborted road projects over the past 30 years, Young told the Chronicle. Unfortunately, whatever work that Young's crew was involved in stopped shortly after the Chronicle story. By then the federal government was focusing more on the overland connection between Canada and the main part of Alaska. But even though the Alaska Highway was eventually built to connect Alaska, interest never went away in Southern Southeast for a connection between Ketchikan, Wrangell and Petersburg and the continental road system. In 1978, the Canadians looked at a connection with Southeast Alaska through the Iskut River when they were building Highway 37. The State of Alaska conducted a similar study in 1984, but at the time it was decided the projected cost, more than $300 million, was too high. In 1998, the Forest Service considered a possible link through the Bradfield Canal, an idea that had the support of powerful state Senator Robin Taylor. It was also later strongly supported by Governor Frank Murkowski when he took office in 2002. British Columbia also expressed interest in a Highway 37 connection through the Bradfield in 2006. In 2004, the Alaska Department of Transportation took a serious look at what it called the SE Mid Region Access Project. The ADOT looked at three different options, all of which involved some 40-50 miles of road on the Alaskan side of the border and about 60 miles on the Canadian side. Considered were a Bradfield option, a Stikine option and Aaron Creek option. Costs (for both the Alaskan and Canadian portions) ranged from $770 million for the Bradfield option to more than $1.2 billion to go up the Stikine from tidewater. A plan for a shorter route up the Stikine was $850 million. The Aaron Creek option was slightly more than $1 billion. The anticipated costs prevented the "Bradfield" cooridor project from moving forward. There was also a change in the British Columbian government in the mid 2000s that turned the province away from large scale projects in wilderness areas. But, as recently as 2015, the Bradfield project was still on the minds of at least some Canadian officials. The Bradfield project came up at meeting of the Regional District of the Kitimat-Stikine, when the board was questioned about its position on a possible road up up the Bradfield and a report was filed. The report noted that newer mining roads into the region would lessen some of the costs of connecting an Alaskan road to Highway 37 but there were other issues that had arisen since the project was studied in the early 2000s. "In addition to the engineering and financial impediments, there are significant institutional challenges to constructing this road," the report, approved on Sept. 2, 2015, noted. "In Alaska, the Bradfield Canal Road would cross the Stikine-LeConte Wilderness Area. On the BC side, a Craig River Headwaters Protected Area was established by the provincial government in 2011." The report noted that all the cost-benefit analyses of the project found that it would only be financially worthwhile if several high-profile mining projects on the Canadian side developed and Alaska then built port facilities at tidewater for shipment of the ore. The district report also noted another potential reason for interconnection: A utility grid between Southeast and BC Hydro. At one point, BC and Alaska had been looking into a connected utility grid, but the report noted that, in 2015, while there was still the potential to hook into Southeast Alaska Power Agency's Tyee Lake facility in Bradfield Canal, but it was not clear whether that alone would be worth the cost to build an intertie to the Canadian grid. A final point, in the regional district report, was that scarce provincial resources should be spent within the province. "The Regional District has never explicitly opposed Bradfield Road construction," the report concluded. "Instead the strategy has generally involved staying informed and being cautious but open to expressions of interest from Southeast Alaska, stating concerns that such a development might divert traffic and economic benefits from northwest communities and the province, and expressing a view that senior government infrastructure investments should be made within BC first to aid northwest BC regional development rather than simply allowing or supporting trans-boundary road access - even if the latter appears to offer at first inspection economic benefits to BC such as improved mine feasibility." Meanwhile, Ketchikan continues to take "baby steps" in extending the local road system outwards. During the intense 2000s debates over the "Bridge to Nowhere" that would have connected Ketchikan to the airport on Gravina, more than a few locals noted that the effort and the money would be better spent on a bridge or ferry access across Behm Canal to the mainland and an eventual road to Canada. It was noted at the time that logging roads in central Revillagigedo Island could be accessed, thus improving access to the "back side" of the island, eventually paving the way for a Behm Canal crossing in the future. In 2007, the ADOT began work on the Shelter Cove road that would connect the Ketchikan road system with the logging roads in upper Carroll Inlet. Although it has taken more than a decade, most of the Shelter Cove road was open to the public in 2020.

On the Web:

Contact Dave at dave@sitnews.us Dave Kiffer ©2021 Publication fee required. © Representations of fact and opinions in comments posted are solely those of the individual posters and do not represent the opinions of Sitnews.

|

||||