Not All Die in CombatKetchikan man was killed in huge munitions explosion in World War IIBy DAVE KIFFER August 26, 2020

Such was the case with Robert K. Hendrickson, an able-bodied seaman in the US Merchant Marine who died in 1944. Many members of the Merchant Marine died during World War II, especially when submarine packs hunted the cargo ships as they crossed the Atlantic and Pacific oceans, but Ketchikan resident Hendrickson did not go down with his ship. He died during a huge explosion when his ship was being loaded with explosives in California.

The Port Chicago explosion was one of the most-deadly non-combat accidents in US history. More than 300 sailors died and tens of millions of dollars in damage was done to the port near San Francisco. The explosion also caused a controversial walk-out by African Americans charged with loading ammunition in the port. The African American sailors were later court-martialed, an action that was eventually overturned long afterwards. Little is known about Hendrickson's time in Ketchikan. He was listed in the 1920 census as the one-year-old son of Knute Hendrickson, who had a sheet medal business in the Newtown area. But neither father nor son was listed in either the 1930 or 1940 census. The Merchant Marine on-line site lists Robert Hendrickson's home as the Ketchikan Gateway Borough, although it is not possible to access Hendrickson's actual merchant marine records because a 1973 fire damaged them.

Henrickson was not listed as a Ketchikan High School graduate in the 1930s, but in those days many residents were allowed to finish school in the eighth grade rather than go on to high school. The story of the ship Hendrickson died on, the Quinault Victory, is very well known. The SS Quinault Victory was the 31st "victory" ship built by the Oregon Shipbuilding Corporation in Portland, Oregon during the war. Its keel was laid down on May 3, 1944 and it was launched barely a month later on June 17th. Victory ships - at 10,000 tons and 455 feet in length - were slightly larger than the "liberty" ships they replaced. More than 500 were built during the War. They had larger engines and were slightly faster than the liberty ships, making them less susceptible to torpedo attacks. Victory ships cost an average to $2.5 million to build in the 1940s. When she was ready, the War Shipping Administration took charge of the Quinault Victory and the ship was leased to the United States Lines Company. The USL operated both troop ships - which were converted ocean liners - and cargo ships like the Quinault Victory.

On July 11, 1944, the Quinault Victory, under the command of Captain Robert Sullivan sailed south from Portland and six days later arrived at the Shell Oil Company's Martinez, California refinery, 35 miles north of San Francisco in the San Francisco Bay. According the military records, the ship took on a partial load of fuel oil. It was later surmised that the fuel could have released highly explosive hydrocarbon gas into the partially empty tanks, but an inspection after fueling found no problems. After the fueling, the vessel left Martinez and made the short trip further up the bay to the Port Chicago Naval Magazine. It arrived at the magazine at 6 pm on July 17th. The Quinault Victory was moored on a berth across from the SS E.A. Bryan, an older liberty ship. The Victory was being loaded with 253 tons of aircraft bombs and five-inch projectiles for 5" naval guns. The Bryan was being loaded 6,064 tons of ammunition including 60 tons on incendiary clusters.

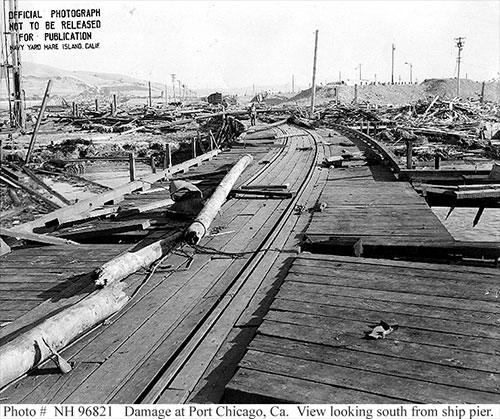

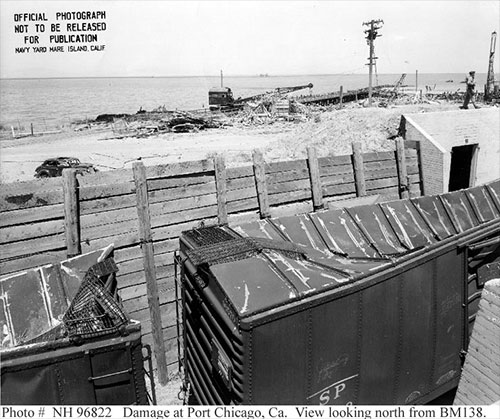

During the loading of the Quinault, some trouble was experienced with the winches, shackles and preventer guy wires, according to later reports on the explosion. At 10:18 pm, two major explosions occurred just about six seconds apart at the dock. The second of the explosions registered at magnitude 3.4 on a seismograph at the University of California, 20 miles to the south. A pilot flying in the area reported that the fireball was 3 mi in diameter. Chunks of glowing hot metal and burning ordnance were flung over 12,000 ft into the air. The explosions essentially vaporized the Bryan, leaving only small parts of the ship left. The 455-foot Quinault was lifted completely out of the water and the largest portion landed 500-feet away in the harbor, upside down and facing the opposite direction from where it was moored. Some 320 sailors - including Robert Hendrickson - were killed instantly and 390 were injured. Of the 320 men killed, almost 2/3 were African-American from the ordnance battalion. Much of the docks were destroyed, striking a blow toward the ordinance loading that was needed for the Pacific theater war effort.

The 12-week span from the keel-laying to the explosion made the Quinault Victory the shortest lived of the Victory ships. Although a lengthy investigation took place, the cause of the explosion was never determined. Some of the few surviving crewmembers reported hearing the sound of a winch or other equipment failing in the hold of the Quinault shortly before the first explosion but that was never confirmed. But the investigation did determine that not all proper procedures were being followed at the time of the munitions loading and that many of the crew involved had not been properly trained. One month after the explosion, more than 250 sailors at the nearby Mare Island magazine refused to load munitions, contending that conditions were as unsafe there as at Port Chicago.

Slightly more than 200 of the men were court-martialed for "disobeying orders" and sent overseas. After the war, they were given bad conduct discharges. The remaining 50 were charged given more serious "mutiny" charges. All 50 were found guilty, reduced in rank and sentenced to 10-15 years at hard labor. All of the convicted personnel were African Americans. Several white sailors who had been involved in the work stoppage were not charged at all. Over the next 50 years, there were several efforts to get pardons for the men convicted of mutiny, but none of the surviving sailors took part because they felt a "pardon" was admitting guilt. In 2019, Congress officially exonerated the 50 men who had been convicted of mutiny. Meanwhile the Port Chicago explosion is commemorated by the Port Chicago Naval Magazine National Memorial on the waterfront near the once destroyed berth of the Quinault Victory. The memorial was dedicated in 1994. Ketchikan's Robert Hendrickson is one of the names on the plaque.

Related:

Editor's Note:

On the Web:

Contact Dave at dave@sitnews.us Dave Kiffer ©2020 Publication fee required. © Representations of fact and opinions in comments posted are solely those of the individual posters and do not represent the opinions of Sitnews.

|

||||||||