The Hygiene sailed Southeast waters looking for TBState focused on stopping 20th Century plagueBy DAVE KIFFER July 07, 2020

According to Bruce Chandler's April, 2017 report in the State of Alaska's Epidemiology Bulletin, TB has been in Alaska for more than 1,500 years, but it only started to effect residents in a significant way as trappers, prospectors and other outsiders began arriving in the mid 1800s. "During that period, TB was a leading cause of death in the U.S. and in many European countries," Chandler wrote. "Tuberculosis spread rapidly among Alaska Native people, a susceptible population living under conditions ideal for TB transmission, especially those with close contact to the incoming colonists. During the first half of the 20th Century, Alaska had some of the highest rates of TB ever seen anywhere in the world."

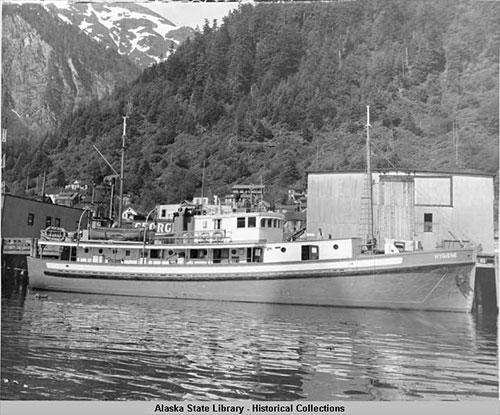

For example, Chandler noted in some areas of Alaska, up to 75 percent of the Native children tested had positive skin tests. In Southeast Alaska, the percent of positive tests for all residents was more than 30 percent. The numbers peaked in the 1930s and 1940s. In those years, when the United States tuberculosis death rate was 56 per 100,000, Alaska Natives experienced a stunning death rate of 1,302 per 100,000. One of the biggest challenges facing the territory as it attempted to deal with the outbreak during World War II and after was the isolation of many of the villages and small towns, particularly along Alaska's thousands of miles of coastline. To deal with the crisis longtime Territorial Governor Ernest Gruening appointed Dr. Earl Albrecht as Alaska's first full time Territorial Commissioner of Health. One of Albrecht's first acts was to establish a "fleet" of boats (two originally) to roam Southeast, Southwest and Northwest Alaska, visiting the far-flung villages and towns, with the equipment to test residents for TB. Eventually, those boats even reached inland communities via rivers like the Yukon and the Kuskokwim. The original boats were the "Health" which patrolled northern Alaska and the rivers, and the "Hygiene" which was primarily based in Southeast. In 1998, Susan Meredith published a book called "Alaska's Search for A Killer," the story of the two years she spent working on the Hygiene as the X-ray technician when she was a young woman between 1946 and 1948.

The book reads like a diary of the time she spent on board: The places the boat visited, the challenges it faced, the people they encountered. The Hygiene based primarily in Juneau, but during her two years on board the boat went as far north as Norton Sound and St. Lawrence Island. In between there and Ketchikan in hit just about every Alaskan community, big and small. "The Hygiene's primary mission was to screen the entire coastal population for tuberculosis," Meredith wrote in 1998. "We were to identify other serious medical problems that appeared and treat them when possible." The main reason the Health Department was screening for TB was to arrange for the most serious cases to be sent out of state to further dampen the spread. At a time when several thousand Alaskans had TB, there were only 70 hospital beds, and one small sanitorium in Skagway, for the patients to convalesce. Most TB patients would have to be sent South for treatment. Meredith's story starts out the Hygiene's shake-down cruise which went from Juneau to Tenakee Springs, where it discovered the majority of the residents had TB. Unfortunately, the majority also refused any sort of treatment, which Meredith found would be a common refrain in Alaska, particularly amongst the white residents, the aging fishermen, hunters and miners that already had a significant "fatalist" streak. The boat continued on to Angoon and Tyee before returning to Juneau and then leaving for Ketchikan. From Ketchikan, the boat visited Kasaan and Metlakatla and returned to Ketchikan before heading out to Rose Inlet, Waterfall, Hydburg, Craig and Klawock. "Visitors started to arrive shortly after we were secured to the dock (in Ketchikan)," Meredith wrote. "When the tide was high they stepped aboard easily, but when the tide went out...the only way on and off the ship was a 20-foot ladder. We who worked on the ship wore jeans and sneakers, but the ladder was a frightening barrier for many of the Ketchikan women, particularly those in high heels and skirts, or those carrying babies." It was quickly arranged for the Hygiene to dock at City Float and access improved. In that initial month-long visit, 3,000 of the 5,000 residents were screened. The town's five doctors, two newspapers and nine churches strongly encouraged all residents to be tested. "In the past, many white Alaskans had dismissed TB as a disease only of the Natives," Meredith wrote. "They did not want to accept that the TB mortality rate in the white population of Alaska was three times higher than in the States." While most of the tests turned out to be negative, the numbers in both the white and native populations were higher that originally estimated when the trip was being planned. During their rare moments of free time, Meredith and other staff members were wined and dined by the Ketchikan locals. Meredith ended up going sport fishing and being invited into numerous local homes. "The conversations ranged from whether Ketchikan's water should be chlorinated, a hot issue, to the merits and disadvantages of statehood," Meredith wrote. "One memorable night a couple of our new friends invited us on a hayride in a truck to a barn dance of schottisches and polkas. It was especially enjoyable because we had always associated hayrides with farming communities, not fishing centers. Moonlight added to the atmosphere and it was a nice contrast to the many nights spent X-raying."

After its two-month circle through Southern Southeast, the Hygiene headed back to Juneau and on to Prince William Sound, Kodiak and the Alaska Peninsula and Cook Inlet. It came back to Southeast for a couple of months in January of 1947, then headed into the Bering Sea as far north as Nome. it didn't return to Southeast until October of 1947. It spent the next eight months revisiting the communities it had been to the year before as well as Yakutat, Kake, Pelican, Edna Bay, Karheen and Hydaburg. In May of 1948, Meredith's tour on the Hygiene was up. On May 10, she boarded the steamer Aleutian for Seattle. Two months after Meredith left the Hygiene and continued on with her life, the boat pulled into Ketchikan for another visit. And there it intersected with my family history. In July of 1948, my mother, Merta Smith Kiffer, was eight months pregnant with my older sister, Janet. Mom never experienced a cough like many tuberculosis sufferers but she knew she was sick and not just in the normal sickness that comes with pregnancy. Later in life she would describe the sick spells as almost like "panic" attacks. She was ordered to rest in bed. The Hygiene was still making the rounds in Alaska and Mom went on board and had an x-ray which showed a spot on one of her lungs. She was told to continue to have x-rays to monitor it. Janet was born in August and Mom stayed in the hospital while Janet was looked after by my grandmother, Edna Smith. Mom's other three children, Ken, Jerry and Dick, were taken care of by my Dad's parents, Jess and Gladys Kiffer out at Clover Pass. Finally, in January of 1949, Mom was sent to Seattle. Her younger sister, Alice, had also been determined to have TB as well and went with her. Mom later said that the residents at the Laurel Beach Sanitorium, in West Seattle had been expecting "Eskimo girls" when they heard the two were coming down from Ketchikan. They arrived in the middle of one of the worst winters in Seattle history. There was heavy snow and temperatures dipped into the low teens. There were snow slides in the hills around Laurel Beach and several houses were destroyed. Then on April 13, 1949, a 7.1 magnitude earthquake struck Seattle. Mom remembered standing in the bathroom of her "cottage" at the sanitorium and watching the toilet bowl shake so hard that the water spilled out it onto the floor. The weather improved in the summer, although Mom said the hotter days were unpleasant in the un-airconditioned rooms at "the San." Then the next winter, the heavy snowstorms continued. It was during that winter, that Mom and several other girls at the San snuck out during a "blizzard" one night and went into downtown Seattle to a club to see Louis Armstrong and his All-Stars perform. Alice was allowed to leave the San in the spring of 1950 and join her husband Vern and children in Bellingham, where they had moved earlier in the year. In June of 1950, Mom was allowed to return to Ketchikan - officials at the San had always contended that she had a fairly mild form of tuberculosis, although it was highly contagious. Mom's other sister Dorothy had also come down with TB and spent some time at a different sanitorium near Bellevue. At Laurel Beach, Mom had been getting "pneumo-thorax" treatments which involved air being pumped into her lungs in order to help the weaker sections. When she got to Ketchikan, one of the local doctors offered to continue the treatments. Mom - who had wanted to be a nurse when she weas younger - always took a strong interest in the details of her treatments and noticed right away that the doctor seemed to be giving her a much higher air pressure than she had received at Laurel Beach. She was concerned but she figured it wouldn't be a problem. It was. The next day, she got violently sick and an ambulance crew had to come to her parent's house on Jefferson Street, carry her out in a blanket and take her to the hospital. Another local doctor, Arthur Wilson Sr., immediately recognized she had been given an oxygen overdose, gave her penicillin and aspirated her lungs, which cleared out the puss and blood that were accumulating. She recovered and Mom always said that "Art Senior" saved her life. In August, Mom was on her way back down to Laurel Beach. She would spend 10 months at "the San" before coming home for good in June of 1951. She noted that - for the most part - residents at Laurel Beach were not bed ridden. They were allowed the freedom to move about the "campus." The main thing the staff was concerned about was that they get enough "rest." If they "behaved" they got an increase in "up" time which meant they could walk about, go down to the beach, and do other things. One of the things they did, was go to "Tony's Tavern" a fancy "shack" down the beach, where residents could hang out and play cards and socialize. And the high spirited amongst the group were always trying to sneak out to see the sights. Mom had a lifelong love for lemons and that led her to go AWOL several times, sneaking out to a nearby store to get some. To help their escapades, the women created a dummy named "Bernice." She had two roles. One was to make it appear that a patient was asleep in her bed, when she was not. The other was to be placed - as a practical joke - in the bed of unsuspecting residents. For years, Mom and her sisters would talk amongst themselves about their time at "The San." It was this somewhat mysterious place that sounded almost like they had been away at college or something similar. It was only much later that I realized they had been swept up in the "plague" that had ravaged Alaska for decades in the 20th Century.

On the Web:

Contact Dave at dave@sitnews.us Dave Kiffer ©2020 Publication fee required. © Representations of fact and opinions in comments posted are solely those of the individual posters and do not represent the opinions of Sitnews.

|

||||||