Battle Between Sheldon Jackson, Father Duncan Played Out In Life of Rev. Edward Marsden March 19, 2012

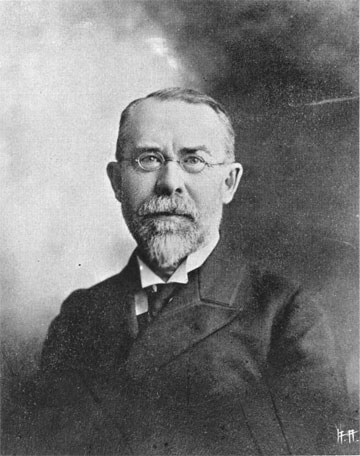

Marsden is often credited in Alaskan histories as being the first Alaska Native to be ordained but that distinction goes to Jacob Netsvetov (Saint Jacob), an Atka Native who became a Russian Orthodox Priest in 1828. Marsden was born on May 19, 1869 in Metlakatla, British Columbia. His mother, Catherine Kitlan, was Father Duncan’s housekeeper and his father, Samuel Marsden, was one of Duncan’s first converts and had been named after a famed Anglican missionary. Duncan himself tutored young Edward in reading and music, in addition to bookkeeping and business. When Duncan took most of his flock across Dixon Entrance to Alaska in 1887, teenaged Edward Marsden, a community boat captain even at that young age, was among the pioneers. (see “The Founding of Metlakatla,” SITNEWS, Aug. 7, 2006 and “Cruising to Alaska, Circa 1887, an Eyewitness to the Founding of Metlakatla,” SITNEWS, Aug. 7, 2007) But soon Marsden began to chafe against what he later referred to as Duncan’s “autocratic control” of the new community. He asked his mentor to allow him to travel outside Metlakatla to further his education and Duncan said no. In response, Marsden wrote a letter, in April 1888, to Sheldon Jackson, then the Commissioner of Education in Alaska. In the letter, Marsden noted that one of the reasons the Tsimpshians had left Canada was because they wanted to be treated “as men, not as Indians.” “I am very anxious to receive further education,” Marsden wrote. “…when you come here you will find me in W. Duncan’s store as I am working there…the only thing I wish very much is to be educated in an American school.” This was the second time that Marsden had asked an outside official for the chance to study elsewhere. In his 1985 book, “The Devil and Mr. Duncan,” Canadian author Peter Murray wrote that Marsden had asked N.H.R. Dawson, one of the dignitaries at the Aug. 7, 1887 Metlakatla founding ceremony, for a chance to attend school in the “eastern United States.” Dawson took up the matter with the Secretary of the Interior and the Commissioner of Indian Affairs. “Duncan should have been pleased by the attention paid to one of his protégés,” Murray wrote. “But he was non committal in his reply to Dawson. He was rigidly opposed to the youths of Metlakatla leaving the community for outside boarding schools.” Murray also noted that Marsden’s mother was opposed to the 18-year-old traveling back east. Marsden’s second attempt would be more successful. Shortly after receiving the letter, Jackson arranged a visit to Metlakatla, according to William Gilbert Beattie’s 1955 book, “Marsden of Alaska: A Modern Indian.” When he arrived Jackson found that Marsden was not the only one wishing to have additional schooling. Twenty Five other boys and young men also asked permission to attend Jackson’s “training school” in Sitka. “Duncan, loath to lose Edward, quietly advised the youth not to go, but the latter felt that he must not miss this opportunity, and with his mother’s consent, decided to go,” Beattie wrote. At Sitka, Marsden was a top student, winning awards for both vocational and academic achievements. Marsden also began a slow, but steady conversion from Duncan’s Anglicanism to Jackson’s Presbyterianism. By 1889, Jackson had named his new protégée “School Prefect” and “Assistant Superintendent.” Then Jackson offered to send Marsden to college at Marietta College in Ohio. Marsden’s mother told him he was needed at home instead. It was a hard decision, but Marsden decided to attend college.

“I made up my mind to go as far as I could go,” Marsden wrote years later “…when Mr. Duncan said it was enough, he and I misunderstood each other right there. Perhaps I was more ambitious than he had planned for me. And perhaps, I overstepped his idea of an Indian education.” Ironically, Duncan and Marsden were on the same steamer heading south several months later. They chatted amicably and later Marsden wrote Duncan that he planned to return to Metlakatla after graduation. But then Marsden joined the Presbyterian Church while at college. During this time, according to Murray, Duncan tried to get Marsden to come home by encouraging his mother to write pleading letters to her son, but Marsden stayed in school. Duncan also wrote to Marsden warning him that much of what he was learning would have little value in the real world and added “In your studies take care not to overwork yourself or try to grasp too much…I have seen students who tried to learn everything, taxing their brains so much they broke down.” “The real reason for his concern however was that Marsden was taking courses in the sciences, history, philosophy and theology which Duncan considered too ambitious a program for a Native,” Murray wrote. In 1893, a serious fire damaged much of Metlakatla, forcing Duncan to – for the first time – seek outside help to replenish the community stores and finances. How Duncan handled the money and supplies that poured in would also be a source of contention between the two men for many years. Duncan expressed concern that the sudden infusion of supplies would “create jealousies” among the Natives and parceled them out sparingly through the community store. Marsden believed that some of the supplies rotted in storage rather than go to those most in need. About this time, Marsden decided to enroll in a seminary. Duncan disagreed and suggested the young man study medicine instead to help the community. In 1894, Marsden also became a United States citizen, the first Native to do, according to Beattie. Marsden enrolled at the Lane Theological Seminary in Cincinnati. When Marsden began studying theology, Duncan told him that he saw little prospect for a future for Marsden in Metlakatka. “Heretofore,” Marsden replied. “I have never minded your constant disapproval and opposition in my pursuit of learning. I have been very faithful to you in spite of your seeming distrust in me and my work; but now my patience can no longer hold out.” Marsden graduated in 1897 and became one of the first Native Americans granted a license to preach in North America. Since Duncan would not allow him to set up a Presbyterian mission on Annette, Jackson arranged for him to be appointed to be the missionary at the village of Saxman, just south of Ketchikan. Saxman had been formed in 1895, when Jackson had convinced the natives of Tongass Narrows and Cape Fox to move north for better opportunities. (see “Canoe Accident Led to the Founding of Saxman,” SITNEWS, Nov. 26, 2009) “Marsden was not keen about the appointment,” Murray wrote. “He told Jackson that he would rather teach at the Sitka school, but reluctantly set out for Saxman in the Summer of 1898.” But Murray noted, both Marsden and Jackson, thought that Saxman would be only a temporary appointment. “Jackson told Marsden that if he built up a good school at Saxman, the Metlakatlans would send their children there to be educated,” Murray wrote. “ ‘If you have a headquarters at Saxman you will be near enough to keep in touch and sympathy with your people, and then when Mr. Duncan dies, I have no doubt they will turn to you as their leader and unanimously elect you to take Mr. Duncan’s place.’ “ While at Saxman, Marsden also helped develop a Tsimpshian community that had sprung up on the Gravina Island – near what is now the north end of the Ketchikan International Airport - (see “The Village of Port Gravina, SITNEWS, Feb. 4, 2006) “The destruction of (Port) Gravina (by a fire in 1904) was a real blow to Edward Marsden,” Beattie wrote. “He had personally aided the people in building their little chapel there and he was recognized by them as their spiritual leader…Mr. Duncan had opposed the Gravina project from the first and looked upon those of his flock who had entered into it as recalcitrants.”

During his first few years in Saxman, Marsden’s mother visited him frequently and he kept in touch with many of his friends on Annette Island. He also drew closer to a Tlingit woman, Lucy Kinnahock, who helped him translate his sermons into Tlingit. They were married in Metlakatla on Octover 3, 1901. According to Beattie, the ceremony was performed by Dr. Montgomery rather than Duncan because Kinnahock – the daughter of a Tlingit chief – had been married before. After they were married, Marsden and Kinnahock adopted her sister’s daughter, who they renamed Marietta Faith Marsden. Later two more of Kinnahock’s sister’s children, Sadie and John, also joined the Marsden household. In addition to his duties in Saxman, the Presbyterian Church also frequently sent Marsden back east to press for support for the Alaska missions. He received good publicity and often encouraged those he met to come to Alaska, one of whom was a young physician in Kansas City named John Myers who came to Saxman and eventually became of the first private practice doctors in Ketchikan, according to Beattie. Murray quotes Myers as being upset by the “conditions” in Saxman and by Marsden’s administration of the mission. Marsden also continued to disagree with Duncan on a variety of matters. But there were moments of “rapprochement.” In 1907, the community of Metlakatla held a 50th anniversary celebration of the day that Father Duncan first came to Port Simpson. The climax of the celebration was a “rendering by a choir of forty Native voices, in excellent manner, of Handel’s reknowned oratorio, The Messiah, under the leadership of Edward Marsden,” according to Beattie. The performing of the Messiah by Metlakatla residents remains a holiday tradition more than a century later. But more often than not, the two men continued their feud. After Sheldon Jackson died in 1909, Marsden further stepped up his efforts to replace Duncan in Metlakatla. It would lead each man into letter writing campaigns to discredit the other, locally and with United States officials. In 1909, Marsden took part in a campaign to establish a new school at Metlakatla that would not be under the control of Duncan. According to Murray, these efforts by Marsden caused him to further neglect his duties in Saxman. Beattie – a long time official of the Presbyterian Church – provided a different picture in his book, indicating that much of the growth of Saxman was because of Marsden’s efforts. In 1915, a schism had developed in Metlakatla between Father Duncan and many of his parishioners and the town council began overriding some of Duncan's authority. Marsden saw his opportunity and moved his family to Metlakatla, while he continued to spend much of the week ministering to his flock in Saxman. By 1916, the situation for Duncan in Metlakatla had grown even more tenuous. In some ways, his community was in open rebellion to his long period of leadership. On January 1, 1916, Marsden was sworn in as secretary of the town council, a position he would continue to hold for the next 16 years. Marsden moved to consolidate his own authority in the community, assuming authority over many of the operations that Duncan had previously controlled.

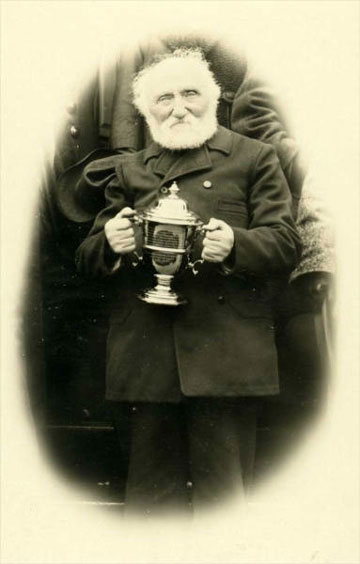

Tlingit woman named Lucy Kininook and Tsimshian man named Rev. Edward Marsden pose for their marriage ceremony, Alaska, ca. 1903

Duncan died in 1918. About that same time, Marsden took over the operation of the Metlakatla Commercial Company. According to Murray, Marsden ran it in a “manner that made Duncan’s payroll deductions seem picayune.” He added that when residents ran afoul of Marsden “the only way to get off the (black) list was to switch from Duncan’s Church to the Presbyterians.” Beattie noted that Marsden’s stature in the community was such that – although there as some opposition from “died in the wool” Anglicans, most of the community supported Marsden and his efforts to establish the Presbyterian Church in the community. “Surely, the principle of self-determination of Indian groups persistently advocated by Edward Marsden from his youth forward was clearly vindicated by his own people,” Beattie wrote. “In contrast, the trustees and supporters of the Duncan Church offered no program except to treat the Indians as indigents.” In May of 1932, the Presbytery of Alaska met in Hydaburg. Although he was not well, Marsden joined a group of ministers and elders on the mission boat Princeton on the trip from Ketchikan to Hydaburg. As the boat was rounding Cape Chacon it was struck by a large wave and both Marsden and Rev. George Beck were knocked to the deck and injured. Marsden’s condition continued to worsen and he was taken back to Metlakatla, where he died on May 6, 1932 at the age of 62.

On the Web:

Contact Dave at dave@sitnews.us

Publish A Letter in SitNews Read Letters/Opinions

|

|||||