& Ball Park & Douglas Bridge. Juneau, Alaska Collection Name: Alaska State Library Courtesy: Alaska State Library - Historical Collections, Juneau, Alaska |

Then, in 1962, the white Presbyterian church in Juneau decided it needed a new facility and convinced the national church organization to provide $200,000 for the new church. It also convinced the national organization to eliminate the separate Native church, a decision the national church now concedes was racially motivated. The reason for the closure given at the time was that Juneau could not financially support two separate Episcopal churches and needed to merge the congregations. But when Memorial closed, a significant number of its members chose not to attend the new, combined church.

If this story sounds familiar to some Ketchikan residents, it should.

Back in the early 1960s, something very similar happened to St. Elizabeth's Episcopal Church, the Deermont church that was also the center of the Ketchikan Native community. Fundraisers, dances, parties and other events made St. Elizabeth's the hub of activity in the Deermont, Nickeyville, Mahoney Heights area of Ketchikan for a quarter of a century.

The story of St. Elizabeth's Church is in a short five-page history written by former parishioners a decade after the closure. There is a copy of the 1977 document in the files at the Tongass Historical Society Museum. The document was signed by 13 former members of the congregation including such Native leaders as Conrad Mather, George Mather, Frieda Driscoll, Doris Volzke and Eleanor and Pauline Williams.

The history traces the beginning of St. Elizabeth's to the arrival of Father William Duncan in Fort Simpson, British Columbia in 1856.

"Because of the harassments and cruel injustices inflicted upon the Indians by the Canadian government and later by the Missionary Society of the Church of England, in 1887, Father Duncan was granted Annette Island as a reserve for the use of the Tsimpshians and other Indians who may wish to reside there."

The history then noted that in early 1900, a group of married couples from Annette Island chose to relocate to Ketchikan for better employment options. In that group were members of the Guthrie, Ridley, Fawcett, Dalton, Williams, Leask, Booth and Mather families.

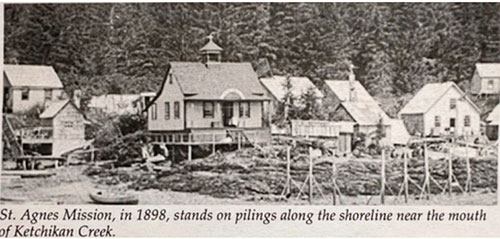

Saint Agnes Mission - 1898 |

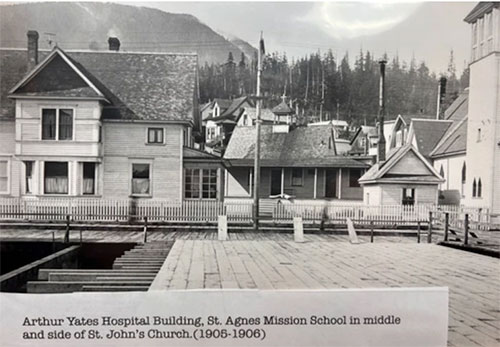

They became members of the St. Agnes Episcopal Mission which had been established when Tlingits from the Fort Tongass area had moved to Ketchikan in the late 1890s. Eventually, the mission expanded to include both Natives and whites and led to the building of the St. John's Church in 1904.

As the church grew, the Native women formed their own guild and called it the St. Elizabeth's Ladies Guild.

"The inability of the white members to accept Indians as competent human beings led to segregation in all church activities," the former church members wrote in 1977. "There was an Indian church school, an Indian evening prayer service, an Indian junior choir and an Indian Ladies Guild. When both races gathered for the Bishop's (Peter Rowe) visitations, the Indians sat on the left side while the whites occupied the right."

According to the former church members, Bishop Rowe became concerned that such treatment would eventually cause the Natives to leave the congregation, and he supported the idea of building St. Elizabeth's Church, although it wouldn't be completed until 1927. St. Elizabeth's would be built in the upland area of what was then called Indiantown to the south of Ketchikan Creek.

Arthur Yates Hospital Building, St. Agnes Mission School in middle and on St. John's Church on the far right. 1905 - 1906 |

Since a "delegation" would have to go back east to seek permission from church officials in New York City. Casper Mather sold one of the houses that he owned in order to finance the trip to New York. He and several family members took a steamer to Seattle and then went by train to the East Coast. The mission was successful and permission to build the new church was received. Bishop Rowe had suggested that a member of the congregation be sent south to be ordained into the ministry. Fred Benson went to Berkeley, California but took ill and died shortly after his arrival.

Paul Mather then stepped in and was ordained a deacon in May of 1927, making him the first Native to be ordained by the Episcopal Church in Alaska. Casper Mather, Alex Guthrie and Robert Ridley also took leadership roles in the new church which opened in July of 1927. A later article in Living Church Magazine noted that the building had been designed and built entirely by Natives.

Paul Mather then went on a lecture tour of the United States with Bishop Rowe, traveling to 45 of the 48 states in two months to help raise money for the new church. Paul Mather would be ordained a priest in 1932 and would serve St. Elizabeth's until his death in in January 1942. Bishop Rowe had remained a good friend and supporter of St. Elizabeth's, occasionally using his personal funds and resources to support the church. He died six months after Paul Mather did.

St. John's Church 1920s |

In 1947, Father Kenneth Watkins took charge of St. Johns and was also given part-time responsibilities to minister at St. Elizabeth's. It wasn't until 1952, a decade after the death of Paul Mather, that St. Elizabeth's got its own minister again.

Then in 1962, the hammer was dropped on St. Elizabeth's. The reason given was finances, although St. Elizabeth's itself was undergoing a remodel at the time that had been mostly covered by church member fundraising.

Although the congregation protested the decision to close St. Elizabeth's and asked for a temporary reprieve to allow St. John's time to prepare for the combined congregation, St. Elizabeth's was closed in May of 1962.

"Because of the hurt feelings surrounding what appeared to be a judgment on the congregation, the majority of them curtailed, if not totally severed their affiliation with the church," the ex members said in 1977. "The building with its furnishings was left untouched for several years...This was the end of an era for the congregation of St. Elizabeth's not because that this was their wish but rather they were over-powered by the dictates of those who did not understand them."

The church building remained empty for many years "to exemplify the evils of injustice."

"And if this merging was done with the hope to establish equality, then it was a mistake and a miserable failure," the former members wrote. "The fact that Indians never show their feelings doesn't mean they haven't any. They prefer to be apathetic and passive instead of resorting to violence as a means of survival. So, without a hearing, without due process, they quietly accepted 'the decision' which was revealed through a long-distance phone call."

Henry Keene Jr. bought the building in the 1960s and held it for several years, hoping that the church would eventually reopen. When it did not, he sold it to Ketchikan Mortuary in the 1970s which continues to own it to this day.

St. Elizabeth's Episcopal Church was built by Ketchikan Native Episcopal Community around 1927, when churches in Ketchikan were segregated. It remained a church until 1962 and now serves as the Ketchikan Mortuary. |

In July of 2005, former members of St. Elizabeth's held a reunion in the old building.

Former church member Martha Johnson, who had been married at St. Elizabeth's in 1959 told the Ketchikan Daily News in 2005 that it was time to move on.

"There were just a lot of people who never went back to church," Johnson said in 2005. "That's why we're having a healing service. I want the people, me, to be able to let it go."

The Rev. Cameron Herriot, the last minister at St. Elizabeth's in 1962, returned 43 years later for the reunion.

Fr. Ron Kotric, who was the St. John's priest in 2005, said he hoped the healing service would serve as a reconciliation moving forward.

St. Elizabeth's does live in on in 2022 in more than memories. The "reconciliation" of the two churches is featured on the St. John's history website.

And several historical pieces from St. Elizabeth's continue to serve in St. John's, including a large oil painting of Elizabeth and Mary, a yellow cedar altar built by Alex Guthrie, pews, vestments and a silver service.

The St. Elizabeth's Bishop's Chair, built by the Rev. Paul Mather, now resides in Petersburg's Episcopal Church.

On the Web:

Columns by Dave Kiffer

Historical Feature Stories by Dave Kiffer

Dave Kiffer is a freelance

writer living in Ketchikan, Alaska. Dave Kiffer ©2022 Publication fee required. © |

Representations of fact and opinions in comments posted are solely those of the individual posters and do not represent the opinions of Sitnews.

Send a letter to the editor@sitnews.us

SitNews ©2022

Stories In The News

Ketchikan, Alaska

Articles & photographs that appear in SitNews are considered protected by copyright and may not be reprinted without written permission from and payment of any required fees to the proper freelance writers and subscription services.

E-mail your news & photos to editor@sitnews.us

Photographers choosing to submit photographs for publication to SitNews are in doing so granting their permission for publication and for archiving. SitNews does not sell photographs. All requests for purchasing a photograph will be emailed to the photographer.