80 years ago local Japanese families were sent to internment campsOhashis were one family that came backBy DAVE KIFFER March 07, 2022

The February 19, 1942 decree was put in place because of concerns that first and second-generation Japanese-Americans would have divided loyalties during the War, even though there was little evidence at the time to support those concerns. In 1976, the United States government formally apologized for the internment and in 1986, it authorized payments to the surviving Japanese Americans. More than 50 Japanese residents in Ketchikan were swept up in the internment, including the Ohashi family.

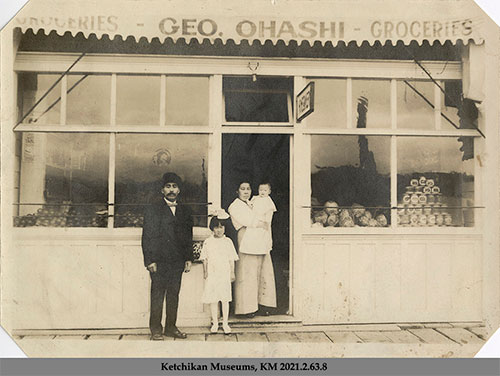

The Ohashi's had first come to Ketchikan in 1900. Jasmatsu "George" Ohashi was from Kawanoishi, Ehime-ken on Shikoku Island and he came to Alaska to take part in the Klondike Gold Rush but only made it as far north as Ketchikan in 1900. Soon other members of his family were also in Ketchikan, including his 12-year-old son Wakaichi "Buck" Ohashi, who first went to Fife near Tacoma, Washington where he lived with an uncle and learned English before coming to Ketchikan in 1910. George's wife Shika- also called Mary - was in Ketchikan by 1905, according to family members. Initially, George Ohashi operated a restaurant called the New York Cafe - which is not the same restaurant as the one operated by the Shimuzu family and still open today. George's younger brother "Tony" was also operating a restaurant on Front Street in 1902, according to an article in Oct. 10, 1902 edition of the Ketchikan Mining Journal. In 1906, George opened a small grocery store at 223 Stedman Street, the heart of what became the Japanese community in Ketchikan. According to George's grandson, Robert Ohashi, all of Ketchikan's Japanese families had businesses within a couple of blocks of each other on Stedman. In a 2011 oral history with the Densho Foundation in Seattle, Robert Ohashi noted that the Suzuki family had a laundry, the Shimizu family had the New York Hotel and Cafe, the Kimura's had a restaurant, the Hagiwara's had a bakery, the Tanino's had a restaurant and that both the Tatsuda's and the Ohashi's had grocery and retail stores. In the 1990 oral history with the Tongass Historical Society, Komatsu Ohashi said she had married Buck in Japan after he returned to Japan in 1924 but that it wasn't an "arranged marriage." She did not know any English and that made it a challenge working in the family store. In those days, customers would go to the counter and tell the clerks what they wanted and the clerks would get it. Because Komatsu could not speak English at first, she couldn't work the counter by herself. She said that she quickly picked up enough English to get by. She said that when Buck first came to the United States in 1900 when he was around 12 years old he had trained with a watchmaker but quickly transitioned into the grocery business and worked with an uncle in Fife, Washington near Tacoma before moving to Ketchikan where his father George was already established. George's younger brother Tony was also in Ketchikan and had opened a restaurant on Stedman Street in 1902 according to a small article in the Ketchikan Mining Journal. George Ohashi threw a wedding reception for the Buck and Komatsu at Jim's Cafe, which was next to the Ohashi store at 223 Stedman. The highlight, she said, was a large quantity of Canadian whiskey that had been smuggled in because Prohibition was still in force in 1924. Although the Ohashi family owned several properties in the Stedman Street area, things were not going well for the family in the late 1920s, Komatsu noted in the oral history.

Komatsu said that someone had convinced George that there was money to be made in running a fish trap and that he had used the family savings and also taken out a $3,000 loan from the Miners and Merchants Bank to fund the building of a trap. But it was not a success - Komatsu said that a series of trap watchmen hired to watch the trap ended up working with fish pirates to steal the fish - and the family was left with a large debt which she said it took 20 years to pay off. George Ohashi died in 1934, she said, and Mary died a year later. Buck took the opportunity to divide the family commercial building into two spaces and one became the Wexelum Bar in 1936. She said the family soon tired of running a bar but kept a liquor store open instead and it was a successful business until the family had to leave during the war. The Ohashi's also ran a pool hall on the property and a card room at different times. The family lived up stairs and there was also space for some borders toward the back of the building. She said that a local lawyer, Harry McCain, who was also the town mayor at one point, helped manage some of their property while they were interned and that it was returned to them in fairly good shape. But other property they owned was given to some families to live in and it was significantly damaged while they were gone, she said.

In general, Robert Ohashi said in his oral history, the family faced little prejudice in Ketchikan and the Japanese children were looked upon as if they were white children in terms of schooling and other opportunities, even though the Japanese families lived South of Ketchikan Creek in the area that was known as "Indian" town. He also noted that his parents didn't teach the children Japanese and did their best to raise them as "American." Several of the families put together a Japanese "culture" center on the hill above Indian town and held some Japanese festivals and offered language classes, but the Ohashi's rarely took part in those, Robert said. At the beginning of the war, before the executive order, Buck Ohashi was taken to Annette Island where he was held with Japanese born males from Southeast. Robert said Buck was allowed to come home briefly, but then taken back to Annette. Buck Ohashi ended up spending most of the war interned in Lordsburg, New Mexico, while his family was sent first to Puyallup Washington and then Minidoka, Idaho. Like many of the generation of Japanese that were interned during the war, Komatsu was not inclined to speak about how the family was treated, only saying - in a 1994 interview with the Ketchikan Daily News - that was military treated the family well. She noted that both the camps, Harmony in Puyallup and Minidoka in Idaho were not well prepared for the influx of internees. Robert noted that - although the families were limited in what they could bring with them - his mother somehow managed to get a washing machine shipped south and that they had the machine at both camps. Komatsu said that she met "many great people" during her time in the camps and kept in touch with them for years afterwards. "I have nothing but great memories," she told the Ketchikan Daily News in a story in 1980. "Oh, we had some hard times, but we came through it."

Robert said he spent most of the time in Minidoka "playing cards" and that for the kids in the camp it wasn't a bad experience despite the confinement. Both he and his mother said the "dryness" of Minidoka was a challenge to get used to. "We (the kids) played basketball, we had dances," he said. "Mom worked in the mess hall. We made friends. There was a little bit of prejudice toward the Alaskan Japanese from the other ones. They acted like they thought we'd be Eskimos or something." He noted that his mother quickly became popular because she could concoct an alcoholic beverage that she gave to the young men of the camp that were draft age so they would fail their physicals. When Minidoka was closed down towards the end of the war, the family relocated to a fruit farm in Idaho that Buck managed, but after a few months, the family returned to Ketchikan. Half of the interned families chose to remain in the Lower 48. Only the Tatsudas, Ohashis and Taninos came back to Ketchikan after the war and stayed. Both Robert and Komatsu said the family was warmly welcomed back. "I remember the police chief (Sam Daniels) came to see us," Robert said in the oral history. "He said he was really happy to see us come home. We really didn't talk much about what it was like in the camps (when they came back). But there were some changes. They were not allowed to reopen the liquor store after the war. Komatsu said the family was told an unnamed city councilman had opposed Japanese families owning such a business and that the council eventually decided the town already had too many liquor stores and denied the Ohashi's liquor license. After the war, the Ohashi's continued to operate the grocery store but also opened an ice cream parlor. Eventually, the grocery business was closed but the ice cream parlor stayed open until the mid 1990s. Buck Ohashi died in 1979 and Komatsu died in 1996. Of their five children; Robert, Paul, Neil, Hope and Edward, Neil was the last to die, in 2016. The Ohashi store building is owned by a local family that hopes to restore it. On the Web:

|

|||||||||

![jpg “Unknown funeral service at Bayview Cemetery, circa early 1930s. We [donor family] assume it is George Ohashi internment.”](http://www.sitnews.us/Kiffer/Ohashi/2021.2.63.1.jpg)