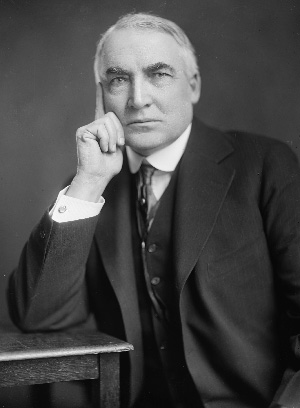

Ketchikan’s only Presidential visitor back in the newsEven if Harding did have a love child, it doesn’t change local historyBy DAVE KIFFERAugust 16, 2015

Ninety some years after his sudden death in 1923, he is back in the headlines as modern DNA testing appears to have concluded that he did father a child out of wedlock. Although rumors of a child nearly kept Harding from being elected President in 1920, most contemporary writers had concluded the rumors either false or unprovable. Of course, Harding has always had a prominent local profile as the only sitting United States President to ever visit Ketchikan, coming to Alaska on a visit shortly before his death. The manner of his death has led some locals to even suggest that Harding died because of something he ate in the First City, although if food poisoning was the cause, it was more likely seafood from Sitka that did it. Historians consider Harding an accidental President. He went into the 1920 election as an also ran in the Republican field, but emerged as a compromise candidate when the Republican Convention deadlocked. Eventually he was nominated on the tenth ballot. Harding, a wealthy newspaper publisher in Ohio, did little campaigning during the general election, preferring to spend most the campaign in his hometown of Marion, Ohio. His main theme was a “return to normalcy” after the years of World War I. He went on to defeat Democratic Party candidate James Cox and Socialist Party candidate Eugene Debs in the general election. Harding’s term began in March of 1921 and ended with his sudden death in August of 1923. His vice president Calvin Coolidge succeeded him.

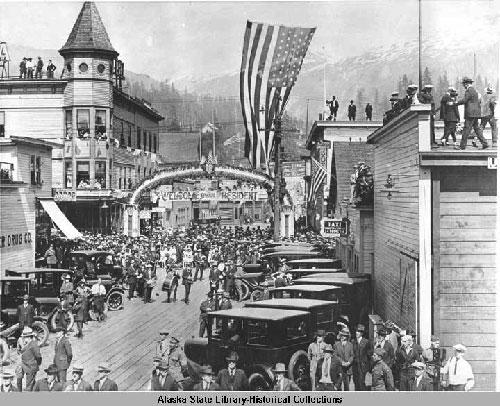

President Harding's Trip to Ketchikan, Alaska, 1923. Although most observers believe that Harding himself was generally not aware of the actions of those around him, his reputation has suffered over the years. Another controversy that simmered before and after he died was whether or not Harding had fathered a child out of wedlock. In 1927, Nan Britton wrote a book called “The President’s Daughter” in which she claimed that she had had a decades long affair with Harding and that her daughter, Elizabeth Blaesing, was actually Harding’s child. Harding’s family denied the claim and many historians also doubted the story. But this past week, it was announced that DNA testing on Harding descendants and descendants of Blaesing indicate that Harding was indeed Blaesing’s father. Harding was apparently a serial philanderer as hundreds of letters from Harding to Carrie Phillips were discovered in 1963 proving another decades-long relationship. Locally, Harding is remembered for his 1923 visit to Alaska. It occurred during the summer of that year and some historians believe that Harding and his advisors planned to use the trip to generate favorable publicity during a time when several of his administration’s scandals were becoming more prominent. The official reason given for the trip, as reported in the July 9, 1923 of the Ketchikan Chronicle, was that a friend of Harding’s had come to Alaska during the Klondike Gold Rush and that Harding had always wanted to visit the area. Carl Anthony, who wrote a 1998 biography of Harding’s wife, Florence, also noted that Mrs. Harding supported the long western trip, more than 15,000 round trip miles, because she wanted the couple to get away from Washington D.C. where they had spent the entire past year. Mrs. Harding relished the opportunity for the couple to make a “grand” public adventure, according to Anthony. The adventure began with a two-week train trip from Washington D.C. to Seattle, where the traveling group boarded the World War I troopship USS Henderson for the voyage north. The entourage was a sizeable one, featuring three cabinet secretaries including Commerce Secretary and future President Herbert Hoover. Hoover had a personal reason for coming along. As a young boy he had spent time in Metlakatla with an uncle who was missionary in the Tshimshian community.

President Harding at Metlakatla, Alaska.

The Ketchikan Chronicle, in reporting on the voyage north, noted that the leisurely voyage on the Henderson up the Inside Passage allowed the Hardings to “recover” from the strenuous train trip which featured numerous political stops on the way. “Both Mr. and Mrs. Harding enjoyed the wonderful scenery between Seattle and Ketchikan,” the Chronicle reported. “Some members of the presidential party were heard to say that if Alaska held no further wonders the scenery along the Inside Passage alone was enough to warrant a trip. “ Harding’s ship pulled into Metlakatla at 4 a.m. July 8, 1923. “All were roused the next morning by a loud Star-Spangled Banner played by a barefoot Alaskan band on an approaching launch, along with Scott Bone, the Alaska Territorial Governor, a former Harding campaign manager,” wrote Anthony in “Florence Harding – The First Lady, the Jazz Age and the Death of America’s Most Scandalous President.” “Harding toured with his party through Metlakatla and went to church, surprised to find Natives waving American flags, the women in short skirts and their black hair in bobs.” During his visit Harding laid a wreath at the grave of town founder Rev. William Duncan, who had died in five years before, in 1918. The Henderson then made the short voyage to Ketchikan. The entire town turned out at the wharf, according to Anthony. “Tricolored bunting and misspelled signs dotted the few wood houses scattered on a mountainside, and there were tours of a new baseball park (Walker Field), freshly painted salmon canneries, a paper factory and a cold storage plant holding four million pounds of fish, some of them 200-pound halibut,” Anthony added. A highlight of the visit, according to the July 9, 1923 Chronicle, was a 12-car motorcade that ushered Harding and his entourage through town. Each car was manned by a “prominent” local who provided tour guide service to the visiting dignitaries. Local women presented a gold nugget necklace to Florence Harding in honor of the couple’s 32nd wedding anniversary.

Ketchikan welcomes President Harding to town. For his efforts, Harding was presented with a souvenir trowel with an engraved sterling silver blade and a fossil ivory handle ringed with gold nuggets, according to the Chronicle. The visit occurred under bright sunny skies, but later, long after Harding had died on the return trip, some Ketchikan residents remembered the weather as being inclement and Harding, hatless in many of the surviving pictures, had potentially caught pneumonia. For two weeks after he left Ketchikan, Harding continued to tour Alaska. Among the things he did on the trip were visiting the new college in Fairbanks and driving the “golden spike” in Nenana signifiying the completion of the Alaskan Railroad. On his way back to Seattle, he made a stop in Sitka on July 22. It was there that Harding reportedly ate some seafood that at least a few commentators, including Anthony, contend killed him. Harding continued to make public appearances including Vancouver, Canada and Seattle, where he gave a speech to more than 20,000 people at the University of Washington. During the voyage south Harding complained of severe stomach cramps. He traveled by train to San Francisco but by then was too sick for additional public appearances. The public was told he was suffering a cold and exhaustion. Needless to say, the American public was shocked when his death was announced on August 2, 1923. Officially, his death was blamed on a cerebral hemorrhage that had possibly been trigged by a minor heart attack that he reportedly had while in Seattle. But many, including Anthony, believe that he suffered food poisoning which led to the heart troubles. Some even believe that he was poisoned by people trying to cover up the scandals that were then coming to light. There are even some who believe that Florence Harding – who took charge of his medical treatment and kept even his closet aides from seeing him his last few days – poisoned her husband because she was fed up with his philandering ways. In Ketchikan, Harding is simply remembered as the only sitting President to visit the community. And Warren, G, and Harding streets are named in his memory. Related:

On the Web:

Contact Dave at dave@sitnews.us

Publish A Letter in SitNews Read Letters/Opinions

|

|||