Simon Dalton |

Dalton was born in Old Metlakatla, British Columbia, a village not far from modern Prince Rupert April 29, 1877, and came to New Metlakatla on Annette Island along with 400 plus other Tsimshian’s who followed Father William Duncan in 1887.

Dalton’s father brought him to visit the tiny community of Ketchikan in 1889, which at that point was just a small salmon saltery and some cabins at the mouth of Ketchikan Creek. The 1890 US Census would note that there were around 40 year-round residents of “Kichikan”. By comparison, Loring had 200 residents and Metlakatla 823.

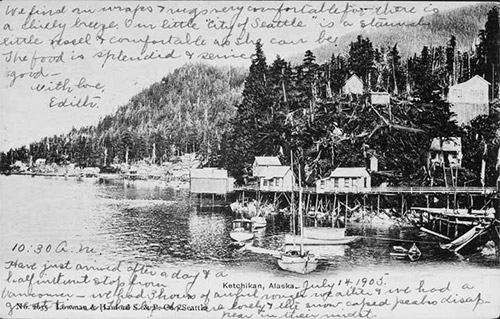

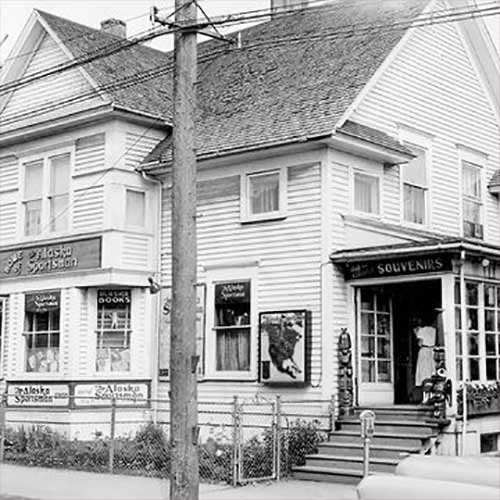

Ketchikan Postcard |

“Ketchikan was no town at all,” Dalton told Tillotson in 1965.

The saltry was located on what is now Dock Street, on the block between Front and Main streets. Dalton said that he remembered no whites living in the small cabins closest to the Creek itself, only Natives, mostly Tlingits. He said he remembered his father using “Chinook” trade jargon to communicate with the Tlingits near the Creek.

“The Tlingits told us that long years ago they had lived on the north end of another island,” Dalton remembered in 1965. “Just lately they had moved over to Ketchikan. There were two tribes together, one on one side of the creek and one on the other. “The people that lived on the south were the Tlingit tribe La Chi Lu. Those that lived on the north side were the Tam-gas. That is a Tlingit name, it is a hard spelling. It is said like Tam-cass.”

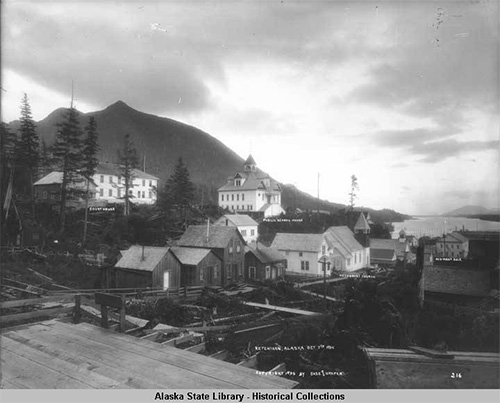

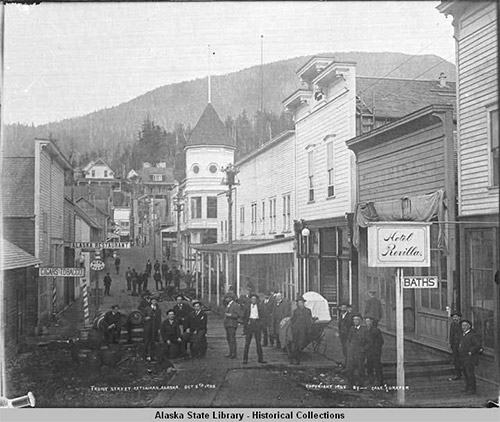

Ketchikan in 1905 |

Dalton said there was a single small store in the village, Clark & Martin, which was close to today’s intersection of Mission and Bawden streets.

“People got supplies there, all groceries and supplies and dry goods too,” Dalton remembered. “Candy for the kids, I was about 10 then.”

Dalton visited Ketchikan several times in the next few years.

“Other white people began to arrive then, prospectors and miners, they came one after another,” he remembered. “They built homes by the north side of the creek. The La Chi Lu people on the south side of the creek moved to Saxman.”

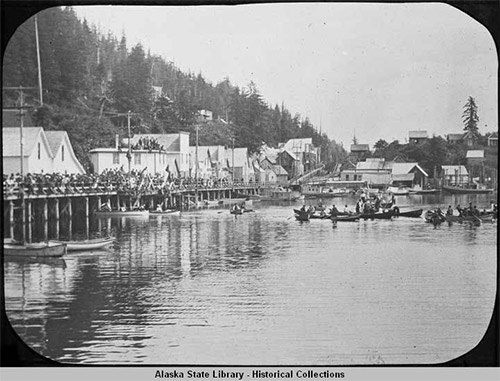

Indian town Ketchikan. |

The Tam-gas, he said, were “all wiped out,” perhaps meaning that they moved elsewhere. The first Ketchikan cannery operated in 1888, adjacent to the original saltery, according to Dalton. But the cannery burned in 1889.

In 1900 the Fidalgo Island Packing cannery was built. south of Ketchikan Creek along what became Stedman Street.

“That’s where I worked, at the cannery,” Dalton said in 1965. “Still more people came. Lots of white people came. Then they built roads. There were no roads for a long time, we had to walk the beaches.”

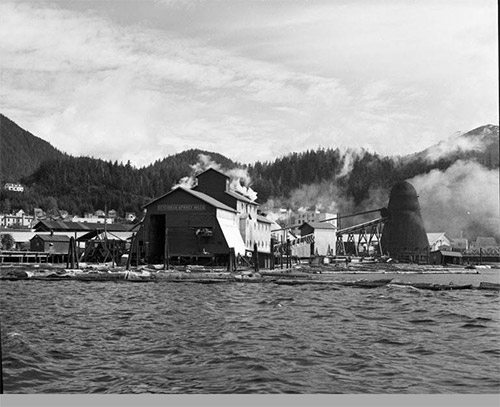

Ketchikan spruce mill. |

He remembered J.R. Heckman moving to Ketchikan from Loring and opening up the Pure Food Cannery that was built adjacent to the Ketchikan Spruce Mill that opened up in 1903. Dalton said that Heckman continued to work in Loring but came to Ketchikan to supervise both his cannery and a new general store, among other business interests.

Dalton said that Heckman found it hard to recruit Ketchikan residents to work in his cannery so he went to Metlakatla and encouraged several families to move to Ketchikan. He said those families lived south of the Creek in the Stedman area which was also referred to as “Indian town.”

According to Dalton, the Guthrie family lived on the hillside behind what was then the Ohashi store and the Mathers had the property to the south of the Guthries. He said the Ridley family had property near Thomas Basin and the Booth and Verney families had land that was close to the where the New England Fish Company and Standard Oil eventually built their facilities even further south on Stedman.

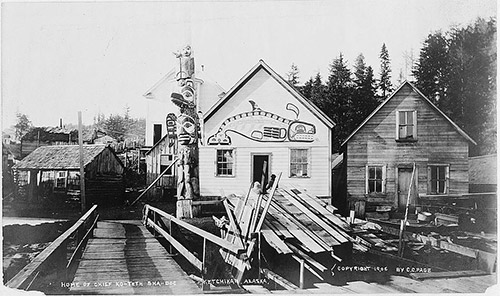

Home of Chief Ko-Teth Sha-Doc, Ketchikan, Alaska: 1906 |

Dalton said that for church services, they had “singing services” in the homes until the Episcopal Church was built in 1903. He noted that Saxman had had an established church beginning when it was founded in 1895 and that Rev. Edward Marsden from Saxman led home services in Ketchikan until the new church was built.

“The (Alaska Episcopal) Bishop Rowe came and was happy to see us singing together. He promised us a church. Next spring, he built the church but just the outside, the inside wasn’t finished,” Dalton said in 1965. “He left it to us Natives to finish it inside. Every service we collected from $5 to $10 or $20. I was the one who collected. Next time we do the same again.”

Unfortunately, Dalton said, about 20 years later, the church was split into separate white and Native congregations and a separate, mostly Native church – St. Elizabeth’s – was built on Deermont Street.

He also remembered the building – in 1904 – of the Yates Memorial Hospital on Mission Street.

Yates Memorial Hospital - Ketchikan, Alaska |

“The whole town helped build the hospital - the Salvation Army, and the Presbyterians did some things to help raise money to build the hospital,” Dalton said. “All the Natives had a show and turned the money into the general fund.”

But, as with the church later, segregation raised its head.

“After the hospital was built when the Natives got sick, they wouldn’t take us in,” Dalton said. “The Natives all got together about it... we asked the Salvation Army and the Presbyterian people and I helped too... (then) the council of this town made it so they will let us in.”

Front Street. Ketchikan. Alaska. Oct. 5th 1905. |

In addition to Heckman’s store, Dalton remembered the building of the Stedman Hotel in 1905 and the Revillla Hotel in 1906. The Revilla burned down in the 1920s and was replaced by the Ingersoll. He said Miners and Merchants Bank opened up in 1906 as well.

“Newtown boomed too,” Dalton said. “And Heckman moved his cannery to Newtown. The Balcom-Payne Cannery was built on the north side (Newtown) 1908 was (also) quite a big time. The New England Fish cannery started up.”

Dalton went to work for Ketchikan Cold Storage in 1918 and worked there for the next 18 years. He was a fish grader and he knew “knew every fish there is.”

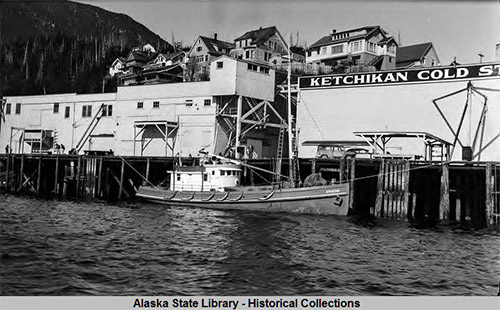

Ketchikan Cold Storage - Date Unknown |

Dalton continued to work for equal treatment of Natives in Ketchikan.

He said that in the mid 1920s, he refused to pay his “school tax” because Native children were not allowed to go to Main School after the Episcopal Mission school closed. Only children that were of mixed parentage were allowed to go to Main School and even that was taken away by the School Board, a decision that was reversed by the Federal District Court in 1929. Meanwhile, the Bureau of Indian Affairs built a school for Native children on Deermont.

In his interview with Tillotsen, Dalton also remembered a serious fishing accident that happened to him in 1936 in Behm Canal.

“One day we got a few fish in the net,” he said. “We started brailing and there was a big jellyfish, a kind of wine color, a long jelly fish. They are poisonous. There are not many of them. They are down deep. I was handling the brailer. The jelly fish rattled around in the water and the water splashed in my eyes. I had no time to wash out my eyes. Just that evening my eyes were gone.”

He was blinded. He said his wife when to the Harry Race pharmacy for medicine and Race sent him to Dr. Wilson but little could be done and Dalton suffered eye problems for the rest of his life.

But even in his mid 80s, in 1965, he still had clear memories of 1889, when Ketchikan was “no town at all.”

On the Web:

Columns by Dave Kiffer

Historical Feature Stories by Dave Kiffer

Dave Kiffer is a freelance

writer living in Ketchikan, Alaska. Dave Kiffer ©2023 Publication fee required. © |

Representations of fact and opinions in comments posted are solely those of the individual posters and do not represent the opinions of Sitnews.

Send a letter to the editor@sitnews.us

SitNews ©2023

Stories In The News

Ketchikan, Alaska

Articles & photographs that appear in SitNews are considered protected by copyright and may not be reprinted without written permission from and payment of any required fees to the proper freelance writers and subscription services.

E-mail your news & photos to editor@sitnews.us

Photographers choosing to submit photographs for publication to SitNews are in doing so granting their permission for publication and for archiving. SitNews does not sell photographs. All requests for purchasing a photograph will be emailed to the photographer.