110 died when Star of Bengal grounded on Coronation IslandBy DAVE KIFFER March 07, 2015

The 9 mile long by 5 mile wide t-shaped island sits in the ocean west of Prince of Wales and south of Cape Decision. It has several harbors but none of which are considered particularly good, according to the United States Coast Pilot, much of the shoreline is sea cliffs ranging from 300 to 1000 feet. Generations of fishermen in the area have steered clear of the island in all but the most fair weather and although a lead mine operated on the island for nearly half a century, the entire island is now part of the Coronation Island Wilderness area. Coronation remains an isolated, generally empty locale, approximately 125 miles west of Ketchikan.

Coronation Island. January 2012

The Star of Bengal was built in 1874 at the Belfast’s Harland and Wolff Shipyard in what is now Northern Ireland. Harland and Wolff was one of the great shipyards in the world and was also the builder of the Titanic in 1914. The Star of Bengal had an iron hull, was 262 feet from stem to stern and had a gross tonnage of 1870. She was owned by J.P. Corry and Co. which was primarily involved in the building trade and as a result, the Star of Bengal frequently transported lumber and building supplies around the world.

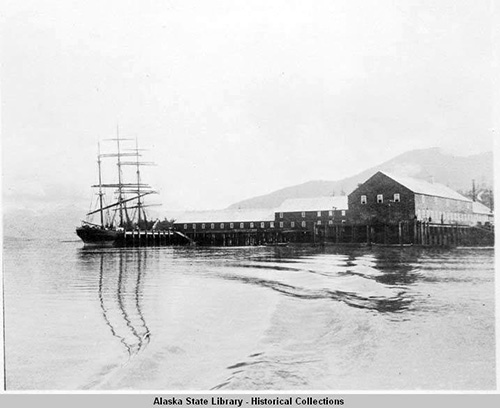

Star of Bengal under full sail. In 1906, she was sold to the Alaska Packers Association, just in time to be involved in the San Francisco earthquake. The Alaska Packers Association (APA) was the largest cannery operation in Alaska from the 1890s through the middle part of the 20th Century, operating as many as 31 canneries in the territory. The canned salmon industry was the largest industry in the state during those decades and accounted for nearly 80 percent of the territory’s tax revenue. One way that the company used to economize costs in its far flung empire was being one of the last major seafaring operations to use “tall ships.” APA used the sailing ships to transport men, materials and product between its canneries and the market centers of Seattle and San Francisco. The old sailing ships were much cheaper to maintain and operate than the new steam powered vessels and APA discovered they were very well suited to operations that usually involved sailing a ship north to a cannery with workers and materials and having the ship spend the season tied up to the dock and filled with tens of thousands of cases of canned salmon. At the end of the season, the loaded ship would leave the cannery and head south where it would unload and winter over in one of the larger cities until it was time to head north the next season. APA began “collecting” the ships of its Star fleet shortly after the turn of the century. Many of the ships came from the Corry Fleet, which was gradually becoming an all diesel fleet.

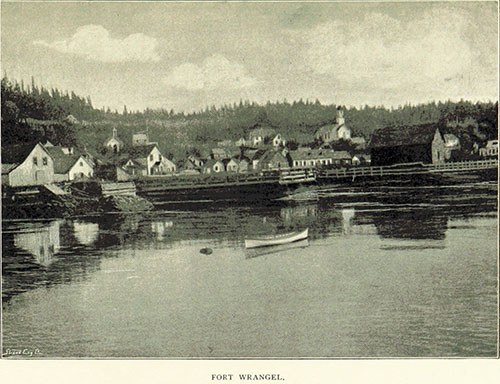

The Star of Bengal joined the APA fleet in early 1906 and was at the dock being outfitted to head north to Alaska when the San Francisco earthquake struck on April 18. Coincidentally, J.A. Heckman, one of Ketchikan’s business leaders and a major force in the APA was also in San Francisco. After the quake, the Star of Bengal captain, an old Southeast Alaska hand named Jimmie Sayles, tracked down Heckman and helped him leave the shattered city. (See “J.R. Heckman, Captain Sayles and the San Francisco Earthquake, SITNEWS, April 18, 2006). On September 20, 1908, the Star of Bengal left what was then still called Fort Wrangel with more than 52,000 cases (more than 2 million cans worth approximately $216,000) of salmon on board as well 134 crewmembers and passengers. More than 100 of the people on board were Chinese and Japanese cannery workers who had spent the summer at APA canneries in the Wrangell area. Most of the foreign cannery workers had been recruited overseas by cannery “bosses” hired by APA, and other companies, to provide a certain number of workers each season. Although some chose to live in San Francisco during the winter, most were on their way home until the next season. Record keeping was poor and there is no accurate accounting of the Chinese and Japanese workers who were on board the Star of Bengal when it left Wrangell, but most contemporary reports indicated it was between 100 and 110. Leaving Wrangell the Star of Bengal was under tow from two smaller vessels, the Kayak and the Hattie Gage. Sailing ships almost never operated under sail in the Alaskan inside waters in those days and were almost always towed out to the Gulf of Alaska before continuing on under sail.

1896 to 1913: Alaska Packers Association Cannery in Wrangell, Alaska, with Star of Bengal at dock. John N. Cobb Photograph Collection : Commercial Fishing in Alaska, 1897-1918. ASL-PCA-122.

What happened next remains a bone of contention in the seafaring community to this day. In order to “save themselves” the Hattie Gage and the Kayak cut the six inch ropes that held the Star of Bengal. The sailing ship soon ran aground near the southern tip of Coronation and quickly broke into three pieces. Roughly two dozen of the people on board made it safely to shore, but the rest, approximately 110 people, drowned. Many of the Japanese and Chinese cannery workers reportedly stayed below decks even after the ship grounded. Captain Nicholas Wagner was among those pulled from the ocean, although he would be later quoted in legal proceedings as wishing he had died in the grounding. Nine crewmembers and four other white non crew members died and were buried on Coronation Island. An effort was made to count the number of dead Japanese and Chinese cannery workers (95) but their bodies were left on the beaches and in the water. Captain Wagner would later accuse the captains of the smaller boats of “criminal cowardice” in cutting the lines, but an official government inquiry would lay most of the blame on Captain Wagner for “sailing” an “unfit boat” into a storm. During the hearing the smaller boat captains had conceded that their boats were not in immediate danger when they cut the ropes, according to a story in a 1909 edition of the San Francisco Examiner. Wagner would appeal that ruling that he was primarily to blame and later win a reversal in court, but his career would never recover. Wagner had already been convicted in the court of public opinion because the skippers of both the Hattie Gage and the Kayak had been interviewed by the Associated Press shortly after accident and had given their perspective that the grounding was a tragedy and had been beyond their control. Captain Farrar of the Hattie Gage was particularly insistent that the two smaller boats were simply too underpowered to control the Star of Bengal in the storm. Farrar told the Associated Press that he only cut the lines when it became apparent that his vessel was nearly surrounded by waves breaking over rocks. He said that the Hattie Gage and the Kayak were forced to seek shelter in a cove 26 miles away from the grounding site, but returned when the storm passed 10 hours later to rescue the stranded survivors from the island. The cable ship Burnside arrived on scene a day after the grounding and reported only the tips of the masts of the Star of Bengal were visible above the water. Over the years, there were no attempts to salvage the cargo because of the location and the lack of a cargo valuable enough to salvage, but several unsuccessful attempts have been made by divers to find the site. In the March, 2005 issue of Sport Diver magazine, there was a report that diver Mike Lever was continuing to try to locate the wreck, although he believed it had been carried into deeper water and was probably covered by sand. Contacted recently, Captain Lever said that he searched unsuccessfully for the remains of the Star of Bengal for five different summers. He said he would love to try again someday. Related:

Contact Dave at dave@sitnews.us

Publish A Letter in SitNews Read Letters/Opinions

|

||