A Tale of Two TotemsCampbell poles graced downtown Ketchikan For two decades, ended up in SwitzerlandBy DAVE KIFFER March 15, 2021

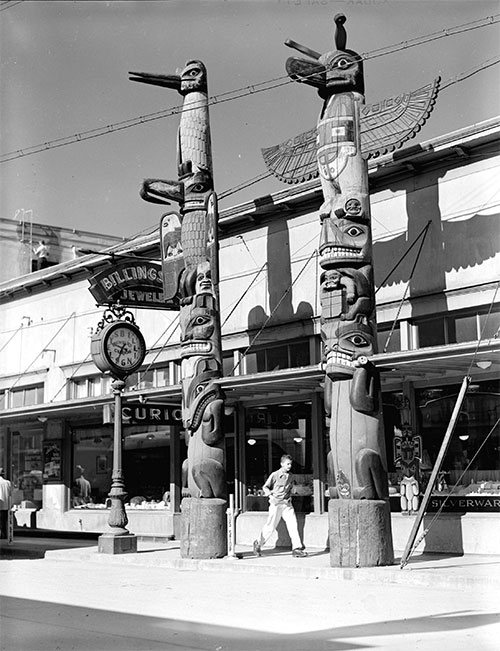

Then suddenly, they were gone. Only to show up again, nearly 6,000 miles away in Geneva, Switzerland, where they remain to this day. The poles even had a moment of Hollywood fame, appearing in the 1954 movie "Cry Vengeance" which was filmed in Ketchikan the year before. At one point, one of the main characters is being "tailed" by another character. When the tailee stops and turns around, the tailer quickly jumps behind one of the poles to hide, although he has already been spotted.

Locals of a certain age still call them the Billingsley totems, although they were carved by Sydney Campbell, one of the original founders of Metlakatla on Annette Island. Because the leader of Metlakatla, Anglican missionary William Duncan, was bent on eradicating as much Tsimshian culture from his flock as possible, Campbell was an outlier. A traditional Native carver who - because of his status - was still allowed to create Native art, but only if it was for sale outside of Metlakatla. Campbell was born in either 1847 or 1849 in the Hudson's Bay Company post Fort Simpson, B.C. (now Lax-Kw'alaams). He would have been around eight to 10 years old when Duncan arrived at Fort Simpson. It is not known exactly when he joined Duncan at his new village of Metlakatla, which Duncan established in 1862. Records show that Campbell was made a member of the Anglican Church in Metlakatla in 1883. But Campbell was part of the community that relocated from Metlakatla B.C. to Annette Island and founded new Metlakatla in 1887. Tsimshian historian Dr. Mique'l Askren Dangeli wrote about Campbell in her 2006 University of British Columbia master's thesis on Metlakatla photographer B.H. Haldane. She noted that Campbell's Sm'algyax name was "Neeshlut" and he was a member of the Gitzontk, an exclusive society of carvers at Fort Simpson. He was occasionally referred to as "Chief Neeshlut" based on his status in the community. Another sign of his status, according to Dangeli, was that photographs of Campbell in regalia in both old Metlakatla (1880) and New Metlakatla (1930) show that he was one of the few who had been to allowed to retain his regalia despite Duncan's banning of it in the new community. Photographs by Haldane also showed Campbell in the company of other carvers, another violation of the rules that Duncan set for the new community. Campbell also had a significant role in efforts by members of the community to take some control away from Duncan in the 1910s. The main issue was education. A significant number of residents were unhappy with how Duncan was running the community school and wanted the US government to establish a government school, separate from the religious one that Duncan had been running since 1887. In 1910, they petitioned the federal government and William Lopp, the Alaska Superintendent of the Bureau of Education, held a meeting in Metlakatla. "At the end of the meeting, Sydney Campbell stood up and sang a Tshimsian grieving song that was used at the death of a chief, signifying the end of Duncan's rule and their approach for governmental assistance," Dangeli wrote in 2006. William Lopp also noted the song in his 1911 report to officials back in Washington D.C. Lopp referred to the song as a "mournful, funeral dirge only sung on occasions of great distress when their chief was dead and they were asking other chiefs for help." Duncan would continue to oppose what was called the "government school" but one was finally built in 1915, three years before Duncan died. A little more than a decade later, in 1930, Haldane would take several photos of the 90-year-old Campbell, with models of totems - including two very similar to the ones that were carved in Ketchikan. He was also photographed with visiting anthropologist Viola Garfield. Garfield would later write "The Wolf and the Raven" one of the standard works on Southeast Alaska totem poles.

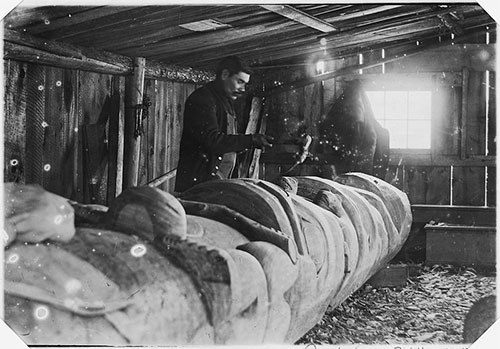

Campbell died in 1934 and was renowned enough to get a large obituary in the Ketchikan Chronicle which lauded him for being the prime mover in efforts for the Tsimshians to get all of Annette Island and not just a small section, which was what was originally proposed by the US government. "Campbell was an excellent boat builder as well as a good carpenter and wood carver," the Chronicle reported in August of 1934, shortly after his July 30 death at the age of 94. "His mind was rich in Indian traditions and folk lore and he was always glad to relate his stories to anyone who was interested in such things." Meanwhile, the two poles that he - with the help of a group of other carvers - had carved held their prominent position in Ketchikan for the 20 years after his death. The poles were carved in Ketchikan because Frank Billingsley wanted something to set his jewelry store apart from several others in the downtown area. Even by the 1920s, there were already several jewelry stores in Ketchikan, hoping to take advantage of the town's salmon canning industry related growth and the increasing numbers of visitors coming to Southeast Alaska via the steamships. Francis Aylwin Billingsley was born in 1900 in Buffalo, New York, according to 1946 story in the Ketchikan Chronicle. His father was a watchmaker and jeweler. In 1912, the family relocated to Seattle. Frank and his brothers Harry and Jim all served in the Canadian army during World War I. In 1924, Frank was living in California and he took a job as watch maker/repairer with Knox Brother's Jewelry in Ketchikan. In 1930, Billingsley bought the shop from the Knox family. In either 1931 or 1932, Billingsley commissioned Campbell to make the two totem poles. It is not clear what price Billingsley paid, but other large poles created in the region at the time were going for between $500 and $1,000 ($15,600 in 2021) each. Billingsley's store also featured work by Casper Mather and Hydaburg carver John Wallace, according to the 1946 story, as well as carved ivory from northern Alaska and slate " totems" from the Queen Charlotte Islands. The Billingsley store continued to operate up the spring of 1954 and then abruptly closed. "The closing out of the F.A. Billingsley Jewelry Store comes as quite a shock to the community," the Ketchikan Daily News reported on March 26, 1954. "Since 1930, when it was opened here, because of its fine display of jewelry, diamonds, gems and artwork, it has been one of the show places for local people and visitors alike." The Daily News reported that Billingsley said he had "interests" in California to look after but that he said he might return to Alaska. Instead, Billingsley died shortly after moving to California. Billingsley's nephew, Walter Winston, said he died of diabetes. The contents of the store were liquidated. But the poles outside the store were different situation. Some locals, including the Mather family, suggested that the city purchase the poles and keep them in the community. But in 1954, Georges Barbey, a retired Swiss banker, purchased them for the Museum of Ethnology in Geneva, Switzerland. Barbey, a 30-year director of the Swiss Bank Corporation, was on a world-wide mission to collect artifacts for the museum, when he came to Southeast Alaska looking for items. The museum has dozens of items that he - as president of the museum's auxiliary society - donated. Over time, Barbey purchased items in North and South America, Africa, the South Pacific and Asia. He was eventually awarded the Medal of the City of Geneva in 1960 for his efforts according to a story in the September 1960 edition of The Rotarian. In a 1951 issue of The Rotarian, Barbey - then 67 - wrote about his interests in collecting artifacts in a story called "I Retired to Adventure" which began on a trip to the Caribbean in 1949. He said that he had been concerned about "being too old for adventure" but had discovered otherwise as he met with tribespeople in remote villages. He said he was happy to continue his adventures and looked forward to visiting other remote areas in the next few years. The cost to purchase the poles has been lost to history, but in a 1989 letter to the Tongass Historical Society, Ralph M. Bartholomew, whose company arranged to ship them, said the poles were insured for $3,000 ($29,000 in 2021) in 1954. After arriving in Geneva, the poles were erected outside the Ethnology museum because they were too large to fit inside. The poles remained outdoors at the museum for approximately 30 years, into the 1980s, when it was decided to take them down and put them into storage. Fiberglas copies were erected in the nearby Parc Gourgas in their place. In 2018, Metlakatla carver David R. Boxley accompanied his father, David A. Boxley, to Geneva to consult on the potential restoration of the original poles. Specifically, David R. Boxley said recently, the museum wanted to know whether the nearly 90-year-old poles could be safely placed upright in the museum. "We determined they could be placed upright but the fire officials didn't feel it was safe to put them in the museum," David R. Boxley said. "In examining the original poles, one thing we determined was that they had been repainted several times and not in what would have been the traditional colors." Earlier, the Boxley's had met in Metlakatla with the granddaughter of Barbey when she came to Metlakatla in 2016 while working on a documentary about her grandfather's worldwide search for items for the museum. Boxley also noted a continuing connection with original artist. He said that his father's apprentice is the grandson of Solomon Guthrie who was a nephew of Sydney Campbell. Boxley said there are continuing discussions with the museum about the creation of a new work that commemorates the original carving. He said that the original poles were carved in the early 1930s. "It was toward the end of his life," he said. "Much of the work was likely done by his apprentices." Boxley also said that the carving was most likely done in Ketchikan because although carvers like Campbell were encouraged to make pieces for sale outside the community, they were certainly not encouraged to do the actual carving of large totems in Metlakatla, even in the 1930s, more than a decade after Duncan died. Boxley said that one thing is clear about the work. "They are not traditional poles," he said. "There is no form line. There are some traditional things such as cheek pyramids, but they are a mix of things. They are not traditional, they were carved for the market, to be sold." It would be another five decades before a pole was actually carved in Metlakatla. Boxley's father carved a pole and held a potlatch in 1983. The first time that had happened since the Tsimshian's moved to Annette Island a century before. "There were totem poles when the Tshimsians arrived on the island," he said. "But they were carved by the Tlingits when the site was still called Taquan." "It's really important to note that the modern day Tshimsian culture in Metlakatla was not continuous with the culture the Tshimsian's had in British Columbia," he said. ""There was a break there. It was a dark time. Even though some carving continued as well as weaving and the language continued, at least until people began being sent off to Native schools where the language was discouraged." Although some people have called for the original poles to be "repatriated" to Southeast Alaska Boxley says there is "no need." "He (Campbell) sold them," Boxley said. "He was an artist who made a sale. They weren't poles that belonged to a clan or family. He didn't use family crests. If they had been taken from his family or his clan that would have been different. But that's not what happened."

On the Web:

Contact Dave at dave@sitnews.us Dave Kiffer ©2021 Publication fee required. © Representations of fact and opinions in comments posted are solely those of the individual posters and do not represent the opinions of Sitnews.

|

|||||