Tatsuda's grocery celebrates centennialFamily's 4th generation operates Stedman landmarkBy DAVE KIFFER May 19, 2016

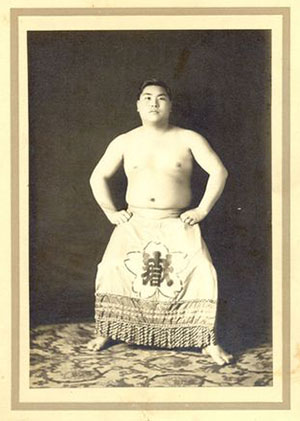

It had been barely 60 years since the American Navy had forced Japan to open itself and its people to the Outside world, but Yawatahama already had a reputation as a growing industrial center for Shikoku. The small city was called the “Manchester” of Shikoku because several of its local industries had already begun to industrialize, particularly the mikan, better known as the satsuma mandarin, production. Yawatahama was also adjacent to the Sadamisaki Peninsula, Japan's longest Peninsula, and was also near Japan’s Island Sea, the seafood rich passage between Shikoku and Japan’s largest island, Honshu. Yawatahama, blessed with a large natural harbor, was the significant seafood port in western Shikoku. In the latter part of the 19th century, jobs were plentiful in the area and by 1889, the town had the first bank in the region and also had the first electric light system on Shikoku. But there was also significant disruption in the centuries old agricultural economy of Japan. That led many Japanese to seek a better economy elsewhere. Between 1886 and 1907, more than 400,000 Japanese men and women went to the United States. So what specifically inspired 18-year-old Kichirobei “Jimmie” Tatsuda to leave Yawatahama in 1904 for an uncertain future across the Pacific Ocean. His grandson, Bill Tatsuda Jr. says the word “adventurer” comes up in notes he took when he visited his distant relatives in Yawatahama in the late 1960s. When he arrived in Ketchikan in 1904, Kichirobei Tatsuda found a world that, at least physically, was not all that different from his home in Japan. There was little flat land in both communities, they clung to steep hillsides above the harbor and both had growing seafood industries. But where Yawatahama had a population approaching 5,000 and been settled for generations, Ketchikan was still a frontier town consisting of few buildings. Ketchikan had only been incorporated four years earlier and its year round population in 1904 was estimated at no more than 300 hundred, although three times as many people were in bustling community during the summer months.

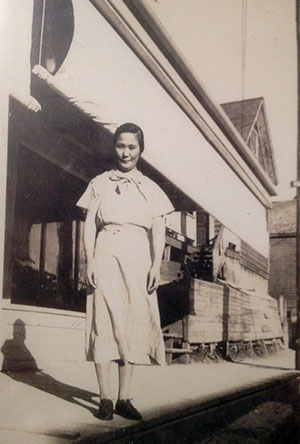

It was the perfect place for a hard worker to get ahead and Jimmie Tatsuda almost immediately began doing odd jobs in the local salmon canning industry which had started with the Fidalgo Island Cannery in 1900. According to family members, “Jimmie” Tatsuda also got a small hand troller and spent summers living on the beach at Bond Bay on across Behm Canal from Clover Pass. Each day he would row his small boat out into the Canal to catch salmon. “They were paid 50 cents per king salmon but could not sell white kings, “ Bill Tatsuda Jr. said recently. “I was showing Ernie Boyd some of the old pictures...and he told me that his mother told him that Jimmie Tatsuda was a cook on the mail boat up north before he got married and they started the store.” In 1913, after nearly a decade in Alaska and approaching 30, Jimmie Tatsuda decided it was time to settle down He let his family in Japan know that he was interested in marriage and his family in Yawatahama found a 19-year-old woman from the nearby village of Uwajima, Sen Seike. After 1907, the American government had severely curtailed immigration from Japan, but there was a loophole. Wives and families of Japanese men living in America could still emigrate. That led to more than 25,000 Japanese women coming to America in the next decade as “picture brides.” The women married the men by proxy in Japan and then arrived in America having never seen their husbands. When Sen Seike arrive in Seattle in 1914, she was carrying a picture of Jimmy Tatsuda. He had also received a picture of her in advance. The Tatsudas made their first home in Ketchikan on Stedman Street in what was called “Indian Town.” Although Ketchikan was not officially segregated in those days, it was clear to most of the residents that white population lived to the north of Ketchikan Creek while all others lived south. In those days, the only grocery stores in Ketchikan were located in Downtown to the north of the creek and residents of Indian town had a lengthy walk. That gave Sen Tatsuda an idea.

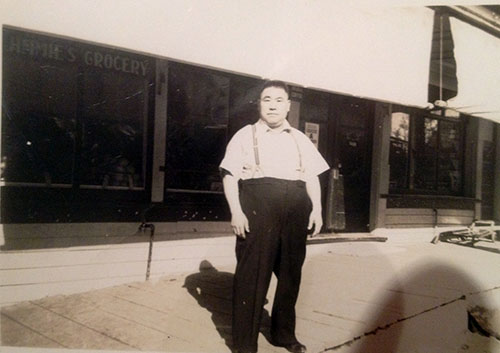

Jimmie Tatsuda standing in front of his first store Jimmie’s Grocery at 415 Stedman Street in Ketchikan.

In 1916, Sen and Jimmie opened up “Jimmie’s Grocery” at 415 Stedman Street, across Stedman from Inman Street. In addition to providing a service to an area of town that did not have a grocery, the Tatsudas also gained a loyal following by extending credit to Natives at a time when no other local store was doing so. During the 1920s and 1930s, Indian town and the neighboring Creek Street were among the most active parts of the community, particularly since Prohibition was completely ignored in the area and the sporting houses drew an active clientele. Jimmie Tatsuda expanded the family holdings by purchasing several properties in the area. And in the late 1920s, Jimmie and Sen were well off enough to afford a trip back to Japan with several of their children. Although the family was thrilled to return home, the trip was also tragic as two of the young boys in the family, one year old John and five year old Thomas, became sick on the trip and died. Another young child in the family also died in the 1920s and is buried at Bayview Cemetery. All of the other children, Jimmy, Cherry, Charlie, Bill, Sarah and Jean, helped out in the store as they grew up and then began graduating from Ketchikan High School in the 1930s. Although the Depression didn’t hit Ketchikan as hard as it did in other places, money was scarce in those years. Bill Tatsuda Jr. says that occasionally he has heard stories from old timers that Jimmie Tatsuda used to loan money to customers who were having trouble paying their bills. Often without being asked to.

But in 1941, the Tatsuda family and their thriving business came face to face with their biggest challenge. When Pearl Harbor was attacked on December 7, 1941, Japanese born residents of the West Coast and their families came under suspicion. In February of 1942, President Roosevelt signed the infamous Executive Order 9066 which called for more than 100,000 Japanese residents of the West Coast to be relocated into internment camps for the duration of the war. That included slightly more than 200 Alaskans, according to Federal records. More than 80 percent of them were Nisei or second generation Japanese Americans, American citizens. Seven families, a total of 42 people, from Ketchikan were amongst the internees. Jimmie Tatsuda was originally sent to Fort Richardson near Anchorage. Other members of the family ended up family ended up in Minidoka, a camp of nearly 10,000 internees near Twin Falls, Idaho. Jimmie Tatsuda was later interned with other Japanese born citizens at a more secure facility at Lordsburg, New Mexico near the Arizona border. In the months leading up to the evacuation, in the summer of the 1942, one of the younger Tatsuda girls, Sara, became severely ill in Ketchikan and died, her family believes of tuberculosis. Several family members had already been sent elsewhere and were unable to return home before she died. Bill Tatsuda says that the Inman family moved into the Tatsuda family apartment above the store and looked after the property while the Tatsuda’s were gone, even occasionally selling snacks to other Indian Town residents. “Delma Inman says that soon after the Tatsudas left town, the FBI showed up at the old store building searching for something and even tearing into the walls,” Bill Tatsuda said. “They did not find anything. Not one Japanese American was ever charged with spying during the war. They were all very patriotic in spite of what the government was doing to them.” Most of the store stock had been given away to area residents shortly before the Tatsudas were evacuated. “A few years ago, Ed Clark came into our store and made a point of telling me that he remembered when the Tatsuda’s were evacuated from town in 1942,” Bill Tatsuda said. “He told me that the Tatsudas gave the people living in Woodland and Deermont neighborhood the food from the store. He remembered getting a big 100 pound sack of rice and other food that his mother really appreciated at the time.” Although some people in Ketchikan supported the evacuation of the Japanese residents, most didn’t. Many years later Pete Johnson angrily remembered having to stand over the evacuees as a member of the Territorial Guard. “These were people that we knew,” he said in an interview with the Ketchikan Daily News in 1981. “They hadn’t done anything wrong.” Joe Diamond was also amongst the local soldiers who had to guard the local Japanese. “I stood guard over the Tatsuda family and one of the girls, Cherry, I went through school with,” Diamond said in the 1995 Ketchikan oral history collection “I Never Did Mind The Rain.” “I cried when she came up the gangway. I had to stand there with a gun over her. That was rough.”

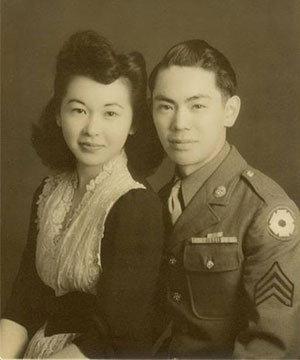

In 1946, several of the family members returned to Ketchikan and reopened Jimmie’s Grocery. Jimmie Tatsuda and sons Jimmy and Bill Sr. - 1948 While some members of the Tatsuda family spent the war in detention camps, others volunteered to fight against both the Germans and the Japanese. Bill’s father, Bill Sr. served in the US Army in artillery unit in North Carolina. His uncle Charlie served in US intelligence in the Pacific. His uncle Jimmy was a member of the legendary 442 Regimental Combat Team which served in Europe. The 442 was made up Japanese Americans, many of whom were family members of the Japanese Americans who were interned during the war. It was one of the most decorated units in U.S. history with more than 1,000 Purple Hearts and 21 Congressional Medal of Honor winners.

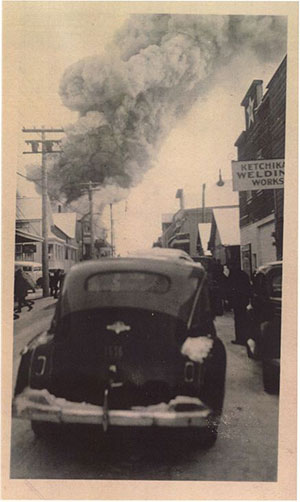

Two of those Purple Hearts belonged to Jimmy Tatsuda who was a sergeant in the 442. “I can remember my uncles talking about friends who were killed or wounded in battle while they were serving together,” Bill Tatsuda Jr. said. “There was no question they were fighting for their country in Europe and the Pacific.” In 1946, several of the family members returned to Ketchikan and reopened Jimmie’s Grocery. Bill Tatsuda Jr. said internment experience clearly convinced family members that their children needed to be as American as possible in the future. “After the war, my generation of Japanese-Americans were not taught the Japanese language, but instead were groomed to be as ‘American’ as possible, excel in school, speak perfect English and be model US citizens,” Bill Tatsuda said. “The only thing Japanese about us was the food we liked to eat. We call ourselves ‘Sushi Japanese.’” In 1947, a fire destroyed the grocery store at 415 Stedman. Several family members barely escaped with their lives. Bill Junior says that family members blamed his father Bill Senior for the fire because he had been thawing frozen pipes with a blow torch, but his father said it wasn’t his fault. “A few years ago, Boots Adams told me that she was shopping in the store when it caught fire,” Bill Tatsuda Jr. said. “She told me that my Grandfather started yelling at her to get out of the store. At first she thought he was mad at her for some reason, before she realized there was a fire. She managed to run outside to the other side of a car that was parked in front of the store. The store exploded and the vehicle was singed on one side but she was unhurt.” The Tatsuda’s reopened the store nearby at 339 Stedman which is the building next to Diaz Café. Once again, family members lived above the store. With Jimmie and Sen looking toward retirement, sons Jimmy and Bill Sr. took over a more active role in running the store.

The store in 1950 at 339 Stedman, is was next to Diaz Café. The family lived above the store.

Bill Junior says that he began working in the store in 1954. “I worked during the summers starting in 4th and 5th grade,” Bill Tatsuda Jr. said recently. “I was officially forced into the business in 7th grade on the threat of having my lunch money withheld if I didn’t go to work after school!” Bill Tatsuda became the store driver when he was 16.

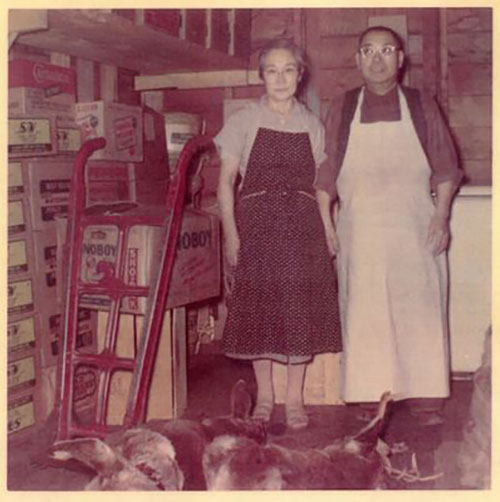

Jimmie and Sen retired in the 1960s and their sons Jimmy and Bill Sr. operated the store. Photo date: 1960s. In 1972, another fire struck the store and this one led to the larger Tatsuda’s at the corner of Stedman and Deermont streets. According to the Tatsuda family, a Ketchikan Public Utilities “brownout” extinguished the boiler flame but did not shut down the fuel pump. Extra fuel accumulated in the boiler and when the power came back on the extra fuel ignited.

Bill Tatsuda Jr. and his father Bill Tatsuda Sr.

“Several of my cousins were working in the store for the summer, and were living in the store at the time of the fire” Bill Tatsuda noted. “We always gave my cousin Timmy a bad time because he was always reading comic books. When the fire broke out late at night he was the only one awake because he was reading comic books and he noticed the smoke coming through the floorboards. He woke everyone up and saved everyone’s lives. “ Unfortunately the smoke damaged a lot of the stock and that led to what Bill calls the “Free Grocery Riot.” “Most of the inventory was smoky and not saleable but was still okay to consume, so we told a few of our customers that they could come in and take what they wanted,” Bill said. “Word spread like wildfire and soon a crowd of people were clamoring to get in on the free grocery event.”

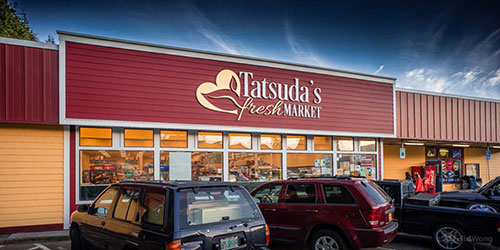

In 2015 the store underwent a significant remodel in time for the groceries’ 100th anniversary in 2016.

The new store would be 10,000 square feet, or ten times the size of the previous one. But the idea for the larger store didn’t find favor with Ketchikan banks that had connections to the owners of the other stores in town, according to Bill Junior. After two years, the Tatsudas finally convinced a bank in Tacoma to loan them the money to build the new store. They also got help from West Coast Grocery. The new store was completed in 1974 and Bill Junior was its first manager.

In 2014, Bill Tatsuda Jr. passed the torch to his daughter Katherine.

Tatsuda’s went from four full-time employees to 15 and ran out of specials within two hours of the beginning of the grand opening, he said.

“It seemed like we learned everything the hard way,” he said. “I remember one time when a frozen food case’s coils iced over and I tried to chip off the ice with a screwdriver. I poked a hole in the copper pipe and the refrigerant leaked out.” Drainage in the parking lot was also a problem and the roof perpetually leaked in the early years. For many years, Tatsuda’s also ran a convenience store, Junior’s, in the NBA building downtown. At different times, Tatsudas was also a partner in the Lighthouse Grocery and managed the Ward Cove Market. Several years ago, it added Gas At Last to its operations. In 2014, Bill Junior passed the torch to his daughter Katherine, who became the fourth generation member of the Tatsuda family to run the store. Naturally, Bill did not “retire” and still can be found most days stocking shelves in the store. He says family members will probably have to “trick him” to get him to really retire. In 2015 the store underwent a significant remodel in time for the groceries’ 100th anniversary in 2016. Katherine Tatsuda’s three children are already spending time at the store, so it appears there could be a fifth generation of the family grocers in Ketchikan’s future.

Members of the Tatsuda Family in 1996

Tatsuda family gathering in 1996.

On the Web:

Contact Dave at dave@sitnews.us

Dave Kiffer ©2016

Publish A Letter in SitNews Read Letters/Opinions

|

|||||||