Redford movie was based on former Ketchikan residentTom Murton was first probation officer and Ketchikan jail managerBy DAVE KIFFER

October 06, 2017

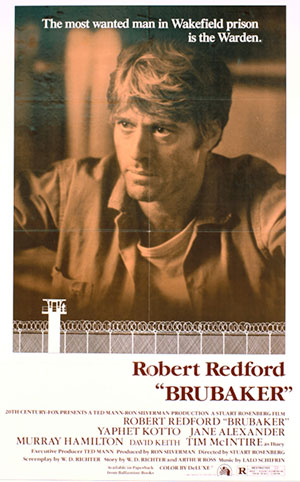

"Brubaker" was loosely based on the story of Tom Murton, a corrections official who indeed attempted to reform the Arkansas prison system before creating a big enough political stir that he was fired. He then wrote a book called the "The Arkansas Prison Scandal." But what is generally not known is that Murton had an Alaskan connection. For several years in the early 1960s, he was the probation officer and the state jail supervisor in Ketchikan. Murton was born in Los Angeles in 1928, but his family had Oklahoma roots and they soon returned to the Sooner State where Murton was raised. After serving in the military, he graduated from Oklahoma State University In 1950 with a degree in animal husbandry. By then, his father had moved north to the territory of Alaska and Murton - who had spent some time in the military in Alaska - joined him there, graduating with a degree in mathematics from the University of Alaska-Fairbanks. When Alaska became a state in 1959, many of the governmental functions of the federal government transferred to state control and the new government was scrambling to find people fill positions in the newly created departments. In 1960, Murton joined the newly created Alaska Department of Health and Welfare. Corrections was a subset of that department within the Division of Institutions. Within that division was the Youth and Adult Authority which had nine separate locations in Juneau, Anchorage, Fairbanks, Ketchikan and Nome. Ketchikan had two facilities, the Ketchikan State Jail which took over the federal jail space in the Federal Building on Stedman Street and the Ketchikan Detention Home - a youth facility that occupied a building next to Norman Walker Ballfield near City Park. Murton began his time in Ketchikan as the first state probation officer. He proved to be a prolific memo writer and, from his memos, we can follow his time in Ketchikan. In January of 2016, State Archivist Dean Dawson poured through the several boxes of records dealing with Murton and created "Tom Murton - His Alaska Connections State and Federal Records Correspondence." The records detailed not only Murton's time in Alaska, but a period nearly two decades later where he was negotiating returning several boxes of the records to the state that Murton may or may not have taken illegally. "Intelligent and conscientious with a dry sense of humor, Murton could also prove abrasive and uncompromising with others, especially his superiors," Dawson wrote into the intro to his collection of Murton memos. "Murton made his reputation by helping establish the Alaskan correctional system...he was eventually fired for giving controversial testimony before the Legislature concerning prison conditions." It would not be the last time that Murton would be fired from a corrections job. "Murton was famous for his exhaustive, multi-page, single spaced memoranda that often contained very few paragraphs, sometimes one paragraph per page." Dawson added. "His 'Murtonian' language was well know within the Department of Health and Welfare." Many of the memos deal with the challenges of staffing and stocking the institutions, according to Dawson. "Murton states that he 'inherited an unique filing system' his way of saying that it was quite inefficient," Dawson wrote. "Murton was involved in the procurement of everything from tooth brushes, cigarette tobacco, shave lotion, shirts, trousers, clamp lamps, plumbing supplies, paper clips, stamps, security razors, uniforms and fingerprint ink rollers. Washing machines were a really big deal." How Murton dealt with all this showed his character as well, according to Dawson. "It...clearly depicts how Murton's style assured his unemployment after a relatively short time with the State of Alaska," Dawson concluded. Murton was working at Clark Junior High School in Anchorage in 1960 when he applied for the position of superintendent in the new Youth Conservation Camp. Charles Pfeffier - the director of the Division of Institutions - decided that Murton wasn't quite qualified to be in charge of an entire facility, but offered him a position as a probation officer. Pfieffer would grow to regret his decision to hire Murton. On August 1, 1960, Murton began his case work in Ketchikan. Murton later wrote - in an unpublished dissertation that is also part of the state archives - that he was also unofficially put in charge of the jail and given the responsibility for hiring officers and developing standards for operations and training. Many of the standards that he developed were then used at other facilities in the state, according the dissertation. Within a week, though, Murton was already developing a reputation as a bit of a "fuss budget." On August 8, he sent a memo to Pfeiffer complaining that every time he switched jobs in Alaska he was required to pay the $10 School Tax again. "No less than four times has this happened to my wife or myself," He fumed, adding that he was willing to take the case to Governor Egan, if necessary. A week later, Murton was still concerned about finances telling Pfeiffer in another memo that he was so low on cash that his family was "down to beans and sow belly now and could use the per diem check very well." Another week later, Pfeiffer was already cautioning Murton to be a little more flexible in his position.

"The only area where I have any concern has to do with a certain amount of rigidity in your personality," Pfeiffer wrote on Aug. 23, 1960. "Such can create more problems than it solves when one is dealing with other human beings. Nothing is ever black and white and there are always two sides to every story. I have become aware of your religious beliefs and have a great deal of respect for them. In this area let me point out something. The Old Testament taught rigidity, an eye for an eye, etc. The teachings of the New Testament, on the other hand, became pliable, turn the other cheek, etc." Two months later, Murton was still peppering Pfeiffer with memos about his pay adding: "If you have has as many problems with your other offices as you have with this one, I fear that, ere long, you will be a candidate for the funny farm. Cherrio." He had also developed - by October - a poor relationship with the Chief Probation Officer, Melvin Ricks. "I fail to see how my statements are in such radical opposition to common sense that I should 'spend some time in close association with an experienced Probation Officer,' " Murton wrote Which is not to say that Murton was entirely unaware that he was rubbing some people the wrong way. In a memo in November of 1960, he apologized the fact that the "second paragraph in cold print appears rather sarcastic" and was not how he intended it. But he also blamed having to report to two different bosses - Pfeiffer and Ricks - as part of the problem. "It takes a while to understand my warped sense of humor so to prevent any misunderstanding I will try to restrict my correspondence to the 'See Dick Run' type of communication," he wrote. "In any event, there was no malice intended and I hope none taken." But, of course, there was plenty of malice being taken. In January of 1961, Pfeiffer offered some friendly advice. "Thought you might like to know that the staff here now jump at the mere mention of your name," Pfeiffer wrote. "If a letter comes from Ketchikan, they put gloves on to open it. You have been nicknamed The Whip...I suggest that you refrain from licking your postage stamps if they come from here. Poison, you know." In January of 1961, the city officially transferred the jail over to the state. The city had been operating it for two years after statehood was approved. The transfer was not smooth, according to a 21-page memo that Murton sent to Pfeiffer. He fumed that the police did not secure their weapons in the jail ("This of course has obvious disadvantages that any six year old moron could comprehend") and he said his negotiations with the city police chief were challenging ("He attempts to cooperate within the limitations of his mentality.") The constant bickering between Murton and the city police would continue for several months."The police chief says is you don't play the way I want to play, I'm going to take my marbles and go home...I believe he has lost most of his marbles and this would make it difficult," Murton writes in March of 1961. He then goes on to savage one of the jail employees he has inherited from the police department saying that he "is unable to cope with any situation. He has no insight, foresight or even hindsight." During this time, Murton also becomes frustrated at the conditions of the Youth Detention Facility which he calls so deteriorated that it is impossible to provide security. He notes that security is so lax that the boys and girls inside seem able to come and go as they please and that he suspects one of the female inmates has gotten pregnant while incarcerated. While he doesn't blame the situation on his boss, Charles Pfeiffer, he tells him that "if it's a boy, we will name it Chuck." Still in the summer of 1961, Pfeiffer wrote several memo's lauding Murton's accomplishments in Ketchikan and statewide, while not dwelling on whether or not he was a good employee. "He has displayed tremendous ingenuity and fine leadership...In all his actions while with the Division, Mr, Murton has displayed....leadership abilities that are needed in the administrative aspects of a correctional program," Pfeiffer wrote in August of 1961. In October of 1961, Murton is frustrated that Pfeiffer has not provided him with enough cards for fingerprinting. So he writes a request directly to J. Edgar Hoover at the FBI. Hoover declines to respond. Also in October he sends a memo to all the corrections staff in the state regarding staff openings in Ketchikan.

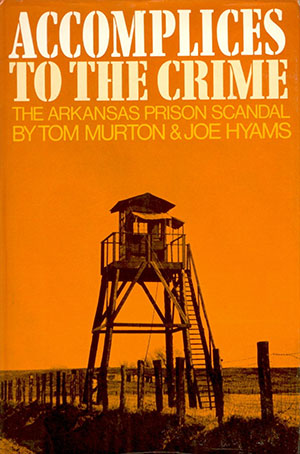

"However, I don't have time to interview every person in Ketchikan who is out of work...somehow you people are giving the impression that there are vacancies at the jail. I have better things to do than to sit and talk to every unemployed person in Ketchikan." In memos for public consumption, Pfeiffer continues to sing Murton's praises but in private memos into the next year, he continues to counsel him to be less negative about situations and look for ways to resolve them without so much drama. He attempted to find constructive ways to use Murton's talents by moving him around the state to deal with issues in other facilities. Eventually he is moved back to Ketchikan early in 1962 as a Corrections Superintendent. The situation continues to deteriorate between Pfeiffer and Murton. "The recent turn of events grieves me deeply and I am sorry that you have taken it as a personal blow...At this point it almost appears as though you have doubts about my integrity and for this I am deeply sorry," Pfeiffer writes in March of 1962. "This program needs your integrity, knowledge, organizing abilities and general know how. But damn it, you must, for our sakes and your own ease off the trumpeting down the middle of the road or nothing approach." And yet, just a few weeks later, a memo shows Murton calling another department official a "jack ass" for not processing his per diem request promptly enough. By January of 1963, Pfeiffer is chastising Murton for purchasing a garter belt in Palmer with state money and Murton is suggesting that Pfeiffer needs to hire a departmental prostitute. Pfeiffer's response? "Tom, your last memo seems to have clearly destroyed all basis for a continued working relationship. For this I am truly sorry." At this point, Murton had been named the superintend of the Adult Conservation Camp in Palmer. Ironically this is one of the positions that Murton had originally applied for three years earlier. In the summer of 1963, Murton decided he needed a break and he applied for a year's leave of absence which was originally granted by the department but then rescinded by higher ups in the state government, citing an apparent error in the application. Murton continued on the Conservation Camp for several more more months, his memos becoming more and pointed, often accusing other state officials with every thing from incompetence to out and out theft. During this time he was finally approved for his educational leave and he was accepted into the graduate program in criminology at the University of California at Berkeley. But he decided to go out with a bang. Interestingly enough, Pfeiffer was still trying to help Murton - or perhaps make it easier to get rid of him. He sent Murton a memo in January of 1964 telling him that he had located two possible jobs for Murton in the Bay Area. Before he left on his sabbatical, Pfeiffer advised Murton that Governor Bill Egan had forbidden all corrections employees from testifying to the Legislature without approval. Murton, of course, went ahead and spoke the Legislative Health Welfare and Education Committee about problems he saw in the correctional department. In April of 1964, Governor Egan ordered Pfeiffer to either fire Murton or resign himself. In June of 1964, Murton was officially terminated when he attempted to return to his job while on break from school. He made a series of administrative appeals over the next three years, but all were turned down. The rest of Murton's life is more in the public record. After graduating from Cal and gaining a national reputation as a rising "criminologist" he was hired to help reform the Arkansas prison system in 1967. He was initially successful at eliminating some of the more punitive and brutal practices in some of the facilities and then was transferred to the state's most hard core facility "Cummins." He learned from one of the inmates that numerous other inmates had been murdered and buried on the prison grounds because they refused to take part in a system in which other inmates, known as "trustees" exhorted other inmates. If an inmate refused he was often killed, buried and listed in the records as an "attempted escape." Murton also reportedly uncovered evidence that the Arkansas prison farms were selling produce they were supposed to growing for the inmates to outside suppliers or trading it in exchange for already spoiled food that was then given to the inmates. The corruption apparently reached into other levels of state government and that was too much for the powers that be. Murton was fired from correctional service for a second time. In an echo of his time in Alaska, the Governor of Arkansas, Winthrop Rockefeller, explained the firing as a result of Murton's "grandstanding" which led to a "totally untenable situation" caused by Murton's "callous disregard for the problems of his equals and his superiors." In 1969, Murton wrote "Accomplices to the Crime: The Arkansas Prison Scandal" which was later turned in "Brubaker." At this point, Murton's career in the penal system was essentially over. From 1971-1978. he taught at the University of Minnesota and tried several times to get hired in corrections where he could further test his theories and his proposed reforms, but he was unsuccessful. Finally, in 1980, he left teaching and returned the family duck farm in Deer Creek, Oklahoma where he would spend the rest of his life. In 1980, "Brubaker" was released and Murton was quoted by People magazine in July saying that the film was "90 percent" true. One part that wasn't was the opening scene where the new warden arrives the prison pretending to be an inmate and goes undercover to find out the true story. "Any warden trying to be a con like that would have been killed either by the guards or the inmates," Murton told People magazine. "If my colleagues saw that they'd hoot." Murton died of cancer in October of 1990 at the age of 62. Toward the end of his life, Murton began negotiating with the Alaska State Library and Archives, attempting to sell several boxes of memos and materials from his years working for the state of Alaska. Archivists and historians such as Robert DeArmond determined that the records were state property and had been illegally taken from the state and should be returned, not purchased. The state eventually agreed to pay for the shipping on the items which are now part of the state collection.

On the Web:

Contact Dave at dave@sitnews.us Dave Kiffer ©2017 Representations of fact and opinions in comments posted are solely those of the individual posters and do not represent the opinions of Sitnews.

|

|||||