The Salmon State

‘Tongass Odyssey’ explores decades of research, politics and change

By MARY CATHARINE MARTIN

May 04, 2021

Tuesday PM

(SitNews) - In 1977, John Schoen flew to Hood Bay on Admiralty Island. He’d been hired as the first Southeast Alaska research biologist to study deer and this was his first trip into the field.

“Flying into the bay, looking at humpback whales and all the bald eagles in the trees… we got out of the Beaver, stepped on the beach and saw these huge, enormous brown bear tracks. And listening to the blue grouse, and the geese on the beach, I just thought ‘Man, I’m getting paid to do this? Unbelievable!’” he recalled.

Mary Beth Schoen admiring a large-tree old-growth stand in Saook Bay on northeastern Baranof Island. Some individual trees were over six feet in diameter and many centuries old. This riparian area was adjacent to a salmon stream and was full of bear trails. Large-tree old growth stands are rare on the Tongass.

Photo By John Schoen ©

|

Forty-four years later, he’s made a career studying and working to conserve deer, mountain goats, brown bears, and Alaska’s ecosystems, and he’s written a book about the journey: “Tongass Odyssey: Seeing the Forest Ecosystem through the Politics of Trees; A Biologist’s Memoir.”

“What we learned is that old growth forest is very important,” he said of research he did with U.S. Forest Service research biologist Charlie Wallmo and fellow Alaska Department of Fish & Game research biologist Matt Kirchhoff. “Clearcuts were used by deer in the summertime, when there was an abundance of food, but in the winter time, when the snows came, the deer couldn’t use them. In the second growth, the deer would have to pack a lunch to make it through. There’s just nothing on the forest floor.

“One thing led to another. We published our results, and then we took tremendous flak from the Forest Service and the timber industry. I quickly realized that the science was hard to do without bumping into the politics.”

A sixty-year-old second growth forest stand on Admiralty Island. John Schoen measured deer density here in comparison to an adjacent old-growth stand. This is a mixed hemlock-spruce stand in which all the trees are the same age and size. Few forest floor plants occur here because of low light levels. These dark, even-aged stands have low structural diversity and provide relatively poor habitat for most wildlife species. In Southeast, it takes two to three centuries before forests that are clear-cut develop the ecological characteristics of old growth. Note the old-growth stump in the left side of the image.

Photo By John Schoen © |

At times, that politics seemed to threaten his job. Twice in the 1980s, he was invited to testify before Congress about his research. Though his immediate supervisors and the then Deputy ADF&G Commissioner were supportive of his work, higher ups in state government were not. The State of Alaska first told Congress he was unavailable — then that there was no money to send him. That wasn’t true. He felt strongly enough about his duty to share what he had learned with the American public that he took annual leave to go testify each time, even taking out a loan to be able to afford the plane ticket.

“I just said, you know, if they don’t want me to go back that much and I have done this work on behalf of the public — it’s a public resource — I have to go back (to D.C.). It’s my responsibility,” he said.

As he branched out into researching brown bears and mountain goats and as his knowledge deepened, he began thinking about old growth forest a different way.

Biologist John Schoen with the Super Cub on a beach on Admiralty Island. The two antennas under each wing were used to determine which direction had the strongest signal from radio-collared animals. They then could locate the animals within an area about the size of an acre.

Photo by John Schoen © |

“The value of old growth isn’t (just) deer habitat. The value of old growth is as an ecosystem. A very unique ecosystem,” he said. “The old-growth forest is a patchwork quilt of all these different kinds of stands, from shore pine to mountain hemlock that may be six inches in diameter and two or three hundred years old. And (different kinds of forest) have a different understory, and they have different values to different species at different times of the year. My evolution has been from looking at the habitat of a single species to looking at the old-growth forest as a very rich, productive ecosystem. People say ‘We’re only logging a small portion of the old growth, so that’s not a problem.’ But they’re focusing that harvest on the rarest, most valuable fisheries and wildlife habitats… Old growth forests are not renewable. You cannot clearcut a forest that has 800-year-old trees in it and expect it to come back in a hundred years to have the same structure and function of an old growth ecosystem.”

Later in his career, he was the lead scientist for Audubon Alaska. In that role, he organized a letter from seven professional societies representing more than 30,000 scientists to then Secretary of Agriculture Tom Vilsack (whom President Joe Biden has appointed in the position once more) about the importance of transitioning out of old growth clearcutting on the Tongass. They never got a response. But he’s hopeful that the Forest Service policy of allowing clearcut old growth logging on the Tongass will change, especially since even more research is coming out, with a recent study estimating the Tongass stores 44% of the carbon in all U.S. national forests.

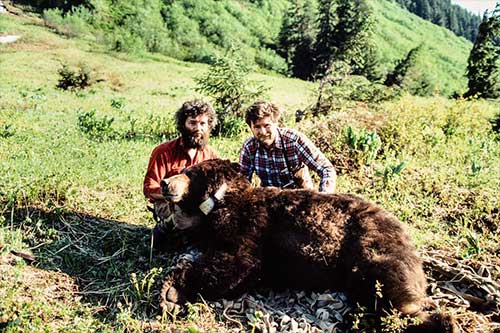

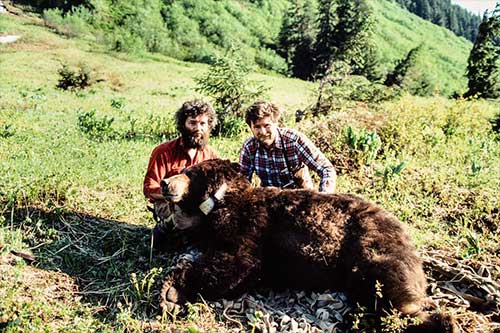

LaVern Beier, left, and John Schoen, right, with a captured and radio-collared brown bear on a subalpine ridge on northern Admiralty Island above Greens Creek. This 547-pound eleven-year-old adult male bear (#46) was captured in June 1986.

Photo by John Schoen ©

|

Schoen published “Tongass Odyssey” in September of 2020, inspired by people’s shifting idea of what was “normal,” the too-slow pace of change he had seen in 40 years of U.S. Forest Service management of the Tongass, and the endangered status of the Tongass’ remaining large-tree old growth, which represents just 3% of the forest.

“I wrote it because I feel it’s important to get this message out,” he said. “I wanted to put down a marker — here’s what’s happened since I started in 1977. And we still haven’t applied the science that we’ve learned to management. It’s been over 30 years, and we haven’t had the political will…. We still have an opportunity to keep the diversity of forest habitats on the Tongass National Forest. There’s no other national forest in the nation where we have this opportunity.”

Tongass Odyssey was published by University of Alaska Press and is available at your local bookstore, on Amazon, or here.

Tongass Odyssey Excerpt:

Part 4: Conservation

I can’t recall when I first began thinking about it, but I suspect my conservation philosophy began to emerge when I was a teenager on Orcas Island, hunting deer in the forest behind our home, digging clams and collecting oysters off our beach, or diving for abalone and rock scallops in the intertidal waters of the San Juan Islands. Our family’s harvesting rule was simple: don’t take more than you can use, and don’t concentrate your taking in one place. That basic approach describes my place-based conservation strategy. After going to college and majoring in biology, my conservation philosophy evolved; after grad school, I gained the tools to ground my conservation philosophy in ecological theory.

For me, conservation includes protecting and managing natural resources — from berries and fish to trees and deer — so that they are available in perpetuity for others to use and enjoy. In 1905, Gifford Pinchot, appointed by President Theodore Roosevelt as the first chief of the United States Forest Service, described the purpose of conservation as managing resources “to provide the greatest good to the greatest number of people for the longest time.” Conservation, in myopinion, includes both preservation and use. But the key is sustainable use and enjoyment of those resources over time measured in decades and centuries.

Early in my career with ADF&G, when I was first doing deer research on the Tongass, I was often asked by forest managers and administrators, “How many deer do you need?” Underlying that question was the assumption that there would always be some deer left after harvesting timber — timber was more important because it provided jobs and a strong economy. The conventional wisdom at that time was that logging benefited deer. However, the more we learned about old-growth forests — including differences in various types of old growth — the more we began to understand that many other species also used old-growth habitat, including bears, marten, flying squirrels, bald eagles, marbled murrelets, goshawks, salmon, and many other fish and wildlife species. And those species depended on a variety of old-growth habitat types that were not necessarily the same as optimal winter deer habitat. In the early stages of our research, it became clear to us that conservation on the Tongass was not just about deer. Fundamentally, conservation was about sustaining the natural diversity and integrity — structure, function and diversity — of the ecosystem.

Aldo Leopold said: “The last word in ignorance is the man who says of an animal or plant, ‘What good is it?’ If the land mechanism as a whole is good, then every part is good, whether we understand it or not. If the biota, in the course of eons, has built something we like but do not understand, then who but a fool would discard seemingly useless parts? To keep every cog and wheel is the first precaution of intelligent tinkering.”

I believe strongly in Leopold’s tenet that the “first principle of conservation is to preserve all the parts.” Keeping all the parts of an ecosystem should be the foundation of any conservation strategy for our public lands. This does not mean that those lands should be protected from any human uses. But it is imperative that all of the ecological parts should be sustained over time. On the Tongass, high-grading the rare, large-tree old growth violates Leopold’s first principle of conservation just as much as threatening the existence of individual species — like king salmon, grizzly bears, or spotted owls — that has occurred on public lands and waters south of Alaska’s border.

The concept of conservation must be broadened beyond simply protecting rare, threatened, or endangered species. It must encompass sustaining the integrity of ecosystems, including species, distinct populations, discrete habitat types, and the natural diversity, structure and function of the ecological communities that make up the greater whole. On an ecosystem level, the whole is greater than the sum of the parts. - John Schoen, Tongass Odyssey

Mary Catharine Martin ©2021

Mary Catharine Martin [mc@salmonstate.org] is an award-winning science and outdoors writer and the communications director of SalmonState.

If you have a story you’d like to suggest for this column, contact her at mc@salmonstate.org.

Mary Catharine Martin is the communications director of SalmonState, an organization that works to keep Alaska a place wild salmon thrive. Part of that effort is storytelling about the Tongass National Forest. Find out more at www.salmonstate.org. |

Representations of fact and opinions in comments posted are solely those of the individual posters and do not represent the opinions of Sitnews.

Contact the Editor: editor@sitnews.us

SitNews ©2021

Stories In The News

Ketchikan, Alaska

|

Articles &

photographs that appear in SitNews are considered protected by copyright

and may not be reprinted without written permission from and

payment of any required fees to the proper sources.

E-mail your news &

photos to editor@sitnews.us

Photographers choosing to submit photographs for publication to SitNews are in doing so granting their permission for publication and for archiving. SitNews does not sell photographs. All requests for purchasing a photograph will be emailed to the photographer.

|

|