B.C. Mines Spark Worry in Southeast AlaskaBy PAULA DOBBYN

March 10, 2014

Spurred by the construction of a major power transmission line, and relaxed environmental regulations in Canada, a rash of mining activity is occurring in the transboundary region, a remote area laced with salmon rivers that joins Alaska and British Columbia. At least ten B.C. mine projects are in various stages of development, according to published reports. Five are located on salmon rivers that flow into Alaska’s southern panhandle, home to the lush, 17-million-acre Tongass National Forest. The mining push comes as B.C.’s provincial government tries to promote development in the sparsely populated region. In a jobs plan unveiled two years ago, B.C. Premier Christy Clark vowed to see eight new mines constructed and nine others expanded by 2015.

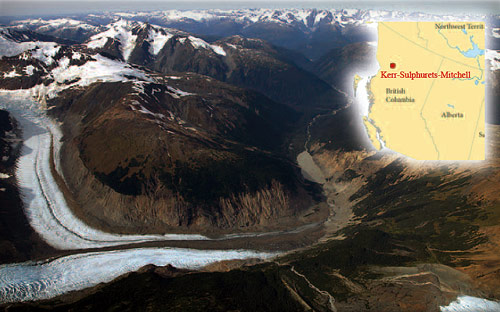

Miners would tear this apart, if the Kerr-Sulphurets-Mitchell is carried through. Glacial water falling down those valleys ends up in Alaska’s Southeast. Any foul contamination from the mine will affect salmon in the Tongass National Forest.

“It couldn’t be in worse location,” said Rob Sanderson of Ketchikan, second vice president of the Tlingit and Haida Central Council, a Juneau-based tribal government representing 28,000 Alaska Natives. “We have five species of Pacific salmon that use this waterway. Salmon is our traditional food.” A major threat Tlingit and Haida is one of several tribal governments in Southeast that have passed resolutions in opposing KSM. And in a recent letter to a Canadian Parliament member, a coalition of Southeast Alaska fishing and tribal groups called on Canada to ensure downstream fish and wildlife habitat is protected and a dialogue with Alaskans is opened.

“Proposed Canadian mining and energy developments in several headwaters within this transboundary region pose a major threat to fisheries and local communities downstream within the U.S. Our concern about Canada’s rush to develop this extraordinary region is compounded by recent legislative initiatives that have weakened Canadian and provincial environmental assessment standards and oversight,” the letter said. The letter referred to recent revisions of Canada’s main fish protection law that makes it more development friendly and less protective for fish, and also to a weakened navigable waters law. “Without strong oversight, new mining projects will likely result in the destruction of fish and wildlife habitat and a diminishment of water quality on both sides of the border. Cumulatively, the effect could be devastating,” the letter said. Among the signers were the heads of Alaska Trollers Association, Petersburg Vessel Owners Association, Southeast Alaska Fishermen’s Alliance, Douglas Island Pink and Chum, and United Southeast Alaska Gillnetters. Tons of Tailings Seabridge Gold, a Vancouver-based junior mining company, hopes to begin constructing KSM later this year. Although it still needs financial backing from a major firm with deeper pockets, Seabridge is moving ahead with permitting. The project is undergoing an environmental review by B.C.’s Environmental Assessment Office. The window for public comment closed on Oct. 21 and the company could get the regulatory green light to proceed in April 2014. The mine’s gargantuan size and location, the acid generating - nature of its ore body, and the need for perpetual water treatment are the main problems, fishermen and tribes said. They also cite the lack of jobs and economic benefits to Alaska. If built, KSM would have an industrial footprint of about 6,500 acres, making it one of the world’s largest gold and copper mines. Plans calls for three open pits as well as an underground operation. The mine would generate over 2 billion tons of tailings and 3 billion tons of waste rock over its lifetime, waste that would require perpetual treatment and containment behind two Hoover-sized dams. Given the complexity of the water-treatment system and the size of tailings’ dams, opponents worry that even if the mine is properly designed, accidents or leaks could happen.

Once the mine is operating and the tailings and waste rock are exposed to air and precipitation, a substance akin to battery acid is generated, which leaches toxic heavy metals from the rock. If released into the environment through surface or groundwater, this type of pollution – known as acid mine drainage – degrades water quality and kills fish, according to the Petersburg Vessel Owners Association. “KSM poses an unacceptable risk to the Unuk River’s salmon resources. We are very concerned that the mine will pollute the Unuk River and its tributaries, which would have significant negative effects on the existing commercial fisheries,” the Petersburg organization said in public comment sent to Canadian regulators in October. Even if an industrial catastrophe never occurred at KSM, any pollution spill or leakage could ruin Southeast Alaska’s reputation for premium wild salmon, according to opponents. Salmon fishing alone in Southeast Alaska is a $1 billion industry that employs more than 7,000 people, or one in ten residents. Southeast Alaska enjoyed a record salmon season in 2013 with an estimated ex-vessel harvest worth $219 million, according to the Alaska Department of Fish and Game. Toothless treaties Fishermen have cause for concern, not just because of KSM and the other mine projects, but because of the lack of tools at Alaska’s disposal to influence what happens across the border, said Bruce Wallace, a Juneau seiner and former president of United Fishermen of Alaska, a trade association representing 36 commercial fishing groups. “The industrialization of British Columbia is bringing on substantive and long-term changes. It’s ironic because the Tongass is just now becoming known as a ‘salmon forest,’ a place that tourists come to actually see wild salmon. And now you have something very contrary to that going on across the border in British Columbia, and there’s no real mechanism to deal with it,” said Wallace. According to Wallace, the two treaties with any bearing on cross-border issues between Alaska and B.C. are the Pacific Salmon Treaty and the Canada-U.S. Boundary Waters Treaty of 1909. But neither contains a trigger that would allow Alaska to enforce standards on how KSM or other mines in B.C. are built. “On these issues, they’re essentially toothless,” he said. Tribal consultation needed Alaska’s best shot at flexing muscle over the B.C. mining boom may be through the U.S. State Department. High-ranking State Department officials should get involved and negotiate directly with Ottawa counterparts, several fishermen and tribal members said. The easiest way to gain the State Department’s ear may rest with tribes. Alaska Native tribal governments are federally recognized as sovereign nations. As such they have government-to-government status with the United States. If they request action on a particular issue, U.S. officials are obligated to respond. In its resolution opposing KSM, Tlingit and Haida Central Council noted “there has been a lack of government-to-government consultation” on the matter. The council said 19 communities of Southeast Alaska, including tribal citizens, depend on clean water for commercial and sport fisheries and for subsistence gathering of fish and wildlife. Subsistence constitutes the “nutritional, spiritual and cultural foundation” for Alaska Natives. “Proper government-to-government consultation must be conducted on all matter regarding mining projects and their impacts on maritime species and subsistence way of life,” the resolution stated. More than 200 comments have been submitted expressing concern about the KSM mine, according to Chris Zimmer, a Juneau sport and personal use fisherman and Alaska campaign director with the non-profit Rivers Without Borders. Alaskans are just beginning to get up to speed on B.C. mining issues, he said, but they clearly see the threats to Alaska salmon and jobs, Zimmer said. More than 70 people showed up at a public meeting in Juneau in October to learn more about KSM. It’s important for Alaskans to get informed even if it can be difficult to track of what’s happening on the other side of an international border, Wallace said. “We have been very successful with managing our fisheries. Alaskans have to live up to incredibly high standards. It’s a whole different story when it’s not our country and it’s not our standards,” said Rep. Beth Kerttula, D-Juneau. “We don’t have direct jurisdiction over mines on foreign lands but if it impacts our rivers we should be more highly involved,” Kerttula said.

Freelance writer Paula Dobbyn lives in Anchorage. Dobbyn is adjunct faculty in journalism at the University of Alaska Anchorage and also works in communications for Trout Unlimited. ©Paula Dobbyn 2014 A publication fee is required. E-mail your news &

photos to editor@sitnews.us

|

||||