Wrangell Rises

Wrangell finds economic health in fishing fleet

By PAULA DOBBYN

August 10, 2013

Saturday PM

(SitNews) Wrangell, Alaska - When an Alaska timber town evolves into something new, a few dead giveaways tell the story. The boatyard overflows, a new harbor immediately fills up, marine-oriented businesses sprout, fish processing plants expand, and the local chatter revolves around a 300-ton vessel hoist arriving from northern Italy.

This place would be Wrangell, population roughly 2,300. Located in Southeast Alaska about 155 miles south of Juneau, the island community of Wrangell is surrounded by the 17-million-acre Tongass National Forest, the country’s largest. It’s a place where the forest products industry long reigned, employing hundreds of loggers, mill workers, longshoremen and others in support jobs. But the days of large-scale timber production have waned and Wrangell is diversifying its economy in a post-logging era. Some steps are paying off. The fishing, seafood processing and maritime industries have all been growing, breathing life and energy into what has been a moribund local economy.

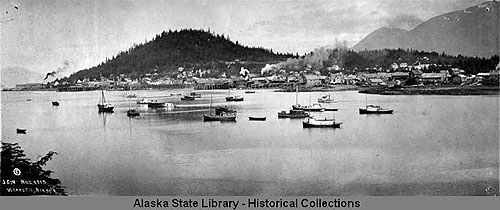

Wrangell, Alaska - August 1913

Collection Name Wickersham State Historic Site. Photographs, 1882-1930s

View across water of Wrangell waterfront; numerous small boats in foreground

Creator Worden, John E. (John Elmer), 1861-1925

Courtesy Alaska State Library

“It’s saved their bacon,” said Juneau seiner Bruce Wallace. “I’d guess about 60 percent of the money coming into Wrangell these days are fish dollars.”

Wallace bases his vessel out of Wrangell. Between dock fees, lift fees, storage and accommodation costs for crew members, and money paid to contractors, Wallace spends tens of thousands of dollars each year in Wrangell getting his vessel ready for the fishing season. He still needs to go to the Puget Sound area to get specialized hydraulic and electrical work done. But most of his vessel maintenance is done locally in Wrangell because of new investments in boat infrastructure and repair, Wallace said.

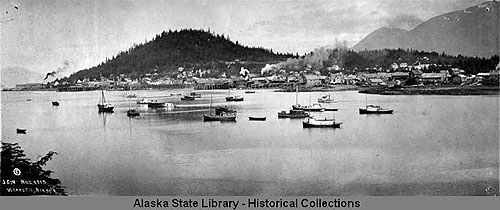

“The maritime sector is booming,” said harbor master Greg Meissner. Showing a visitor around the crowded docks and waterfront, Meissner points to the myriad signs of Wrangell’s emergence as regional maritime hub. One of the most obvious is the sheer number of boats visible from downtown. Seiners, trollers, gill netters, yachts – all types of working vessels and pleasure crafts dot the waterfront.

Wrangell, Alaska

Photo courtesy Wrangell Chamber of Commerce

www.wrangellchamber.org

“I never remember there being anywhere near this number of boats when I was young,” said Jean Gamache, an Anchorage resident whose mother is from Wrangell. She visited Wrangell this past summer for a clan house rededication.

Meissner, who grew up in Wrangell, confirmed Gamache’s observation that the town is undergoing a maritime renaissance.. With his job managing the city’s harbors, he sees evidence of it every day.

He drives his white pickup truck around a ship yard and boat haul out that formerly housed the Alaska Pulp Co. sawmill. Once the town’s dominant employer, Alaska Pulp Co. quit Wrangell amid a region-wide industry downturn in 1994, throwing the blue-collar community into economic turmoil. The recovery remains a work in progress, city officials say. But with multi-million-dollar investments from the public and private sectors, Wrangell has decidedly entered a new chapter – one largely built around the ocean and fish, particularly salmon.

Besides the visual clues that Wrangell is changing, taxes collected by the city underscore where things are headed. In 1990, Wrangell collected $55,483 in raw fish taxes. By 2012, the figured had more than quadrupled to $265,498.

“There’s a lot more product that’s being run through Wrangell these days,” said Jeff Jabusch, city finance director. “That’s the direct result of steps we’ve taken to encourage more boats to come to Wrangell, the investments we’ve made in infrastructure, and moves taken by the processors to expand.”

Revenue is also up dramatically from harbor fees. According to data provided by Jabusch’s office, Wrangell took in $135,719 in stall rentals and transient moorage fees in 1990. In 2012, the number jumped to $493,698.

Wrangell’s 150-ton lift soon will be complemented by a 300-ton lift.

Photograph By

Paula Dobbyn ©2013

Wrangell’s economic transition from timber to fishing, seafood processing and all-things-maritime has been slow and steady and not always easy. The Alaska Pulp Co. sawmill closure sent the unemployment rate up to 20 percent practically overnight. The town’s other medium-sized sawmill, Silver Bay Logging, struggled to continue operating but finally closed five years ago. No new industries organically swept in to replace what was lost. A few micro-sized mills that do custom orders and niche manufacturing are still operating and there’s interest in growing that sector. But it’s clear from the investments that the city, state and private sector have made that the future is being built largely around fish with a secondary focus on tourism.

Soon after the mill closure, Wrangell began a series of steps to shore up its economy. In 1997, the town did a feasibility study looking at the pros and cons of converting the old mill site downtown into a marine services center and boat yard. It ended up penciling out. Later the city purchased a seafood plant, and with funds received from Congress from a timber-industry disaster fund, Wrangell invested in a belt freezer to flash-freeze fish and the city also put in a cold storage. Trident Seafoods ultimately bought what was then called Wrangell Seafoods and has been expanding the plant almost every year, said economic development director Carol Rushmore. Sea Level Seafoods, Wrangell’s other big seafood processor, has also invested in and expanded its plant, she said.

Greg Meissner is Wrangell’s harbor master.

Photograph By

Paula Dobbyn

|

Other steps have included building Heritage Harbor, a new boat basin – one of three in Wrangell -- that can accommodate more than 165 boats, in addition to having 1,500 feet of transient moorage space. The harbor was finished in 2010 and is packed, with the exception of a few berths, for some larger-sized vessels, Meissner said.

Wrangell also built a convention and visitors center, and upgraded its cruise ship dock and main drag, called Front Street, with the goal of attracting more visitors to the community. Some of its natural assets include the Stikine River, with its bears, moose and thousands of migrating birds in spring and fall, as well as the LeConte Glacier and the Anan Bear Observatory, which offers some of the best bear viewing in the world.

Of all the investments Wrangell has made so far, the transformation of the old sawmill site downtown is perhaps the most successful, a testament to the town’s emerging identity and willingness to embrace new economic opportunities beyond timber. The new marine services center is a beehive of activity for boat design, repair, fabrication, painting, welding, custom glasswork, hydraulics, and other businesses.

“It’s been a huge success,” said Jabusch.

Since Wrangell has geared up to accommodate the fishing industry, Wallace has saved thousands of dollars not having to journey to Washington State to get his boat worked on all the time, he said. If even more specialized businesses moved into town, he would be able to avoid heading South entirely, Wallace said.

“They just need to tool-up a bit more.”

The Alaska Legislature appropriated $9.8 million in 2012 and 2013 for upgrades to the marine services facility. This year it allocated $2.7 million for a 300-ton boat lift so that Wrangell can accommodate and service bigger vessels than it currently can handle, according to data provided by the office of Sen. Bert Stedman, R-Sitka.

Southeast Alaska’s timber industry thrived until the 1990s. It was built largely around two large pulp mills that operated in Sitka and Ketchikan along with several sawmills in towns including Wrangell and Metlakatla. Industrial-scale logging, pulp production and sawmilling kept several hundred workers employed in high-paying, year-round jobs. Underpinning the timber industry were a pair of 50-year contracts the Forest Service issued to Ketchikan Pulp Co. and Alaska Pulp Co. The contracts pledged to supply the companies with 13.5 billion board feet of timber from the Tongass National Forest, a coastal temperate rainforest that blankets the Southeast Alaska panhandle. At 17 million acres, the Tongass is twice the size of Maryland and represents the largest temperate rainforest in the Northern Hemisphere, according to the Forest Service.

For four decades, the Ketchikan and Sitka pulp mills and associated sawmills consumed large volumes of Tongass old-growth timber, churning Sitka Spruce, Western hemlock, and red and yellow cedar logs into forest products, including pulp, saw logs and wood chips. The industry hit its heyday in 1990 when Southeast Alaska lumber exports peaked at 225.5 million board feet. The combined wood-products industry that year enjoyed a record export value of $641 million, according to the Alaska Division of Economic Development. Things changed dramatically for the industry soon afterward. Increasing market pressures, an Asian economic crisis, tougher regulations by the Environmental Protection Agency, logging cutbacks imposed by Congress through the Tongass Timber Reform Act, and numerous environmental lawsuits soured the business climate for the timber industry. The Alaska Pulp Co. mill in Sitka closed in 1993 followed by the Ketchikan Pulp Co. mill in Ketchikan in 1997. The industry has downsized ever since although a medium-sized sawmill in Klawock on Prince of Wales Island continues to operate as well as several niche manufacturers in Wrangell, Hoonah, Tenakee Springs, Craig, Gustavus, Juneau and Thorne Bay. |

|

“The goal is to capture more of the marine support economy and bring it up here from Puget Sound,” said Stedman.

Government appropriations can sometimes turn into boondoggles, said Wallace. Not so in the case of Wrangell.

“It’s been a quiet success story. That place could have easily turned into Ghost Town, USA,” the Juneau seiner said.

The larger boat lift is supposed to arrive from Formigine, Italy, soon. The 150-ton vessel hoist the city currently owns arrived in 2008 and it’s been a boon to the economy, Meissner said.

“See over there?” the harbor master says, pointing to a huge tent-covered area with several men in Carhartts and Xtratufs milling around a boat. “There’s three guys over there doing fiberglass work. Those are new jobs.”

He points to several other massive tents, each covering a different business that’s somehow related to boats, fishing, processing and maritime. Chuck Jenkins, owner of Jenkins Welding, is among those who expanded his business as a result of the marine services center going in. Jenkins has a shop a few blocks away but also opened an extension down at the boat yard.

“It’s been great for my business. Some months I’m booked up two years out,” Jenkins said.

Meissner edges the truck close to fisherman Brian Rooney’s troller. The hull of Rooney’s boat is nestled into the straps of a 150-ton hoist, a remotely-operated machine that lifts boats in and out of the water. Repairs to Rooney’s vessel have wrapped up and it’s time to return it to Zimovia Strait. A narrow waterway on the east side of Wrangell Island, Zimovia is an artery of Southeast Alaska’s scenic and salmon-rich Inside Passage.

Meissner and a visitor watch as a harbor employee switches levers on a waist-mounted remote control system that operates the boat hoist. He adroitly maneuvers the troller closer to the water, easing it down a pier that opens to the sea. The rusty metal boat splashes back into the water. Rooney fires up the engine and steers the vessel into the cold grey water.

“That’s how the 150-ton lift works,” Meissner says, his eyes gleaming. “When we get the 300-ton one here, we’ll have even larger vessels coming to Wrangell.”

Bigger boats, including fishing tenders, should mean more jobs and more income for Wrangell, city officials predict.

But Wrangell’s maritime and seafood industry expansion has meant the shipyard is already bursting with fishing and pleasure boats. So where are the larger vessels going to fit?

“We’re going to work with the existing space but it would definitely be good to expand out,” said Meissner. “There’s a site out the road we’re interested in but right now the city doesn’t have the money to buy it.”

He’s referring to the former Silver Bay Logging sawmill at Shoemaker Bay, about five miles south of town. The defunct lumber manufacturer was demolished and the site cleaned up a couple of years ago. The parcel is currently for sale and the city is eyeing it.

Meanwhile, improvements to the marine services center continue. In early spring, electricians were installing underground lines and paving crews were getting ready to pour concrete so that the yard -- surrounded by a rainforest -- isn’t constantly muddy.

Front Street looked busier than it has been for years.

“Four years ago when I was there, I stood on the main street and waited 20 minutes before a single car drove by. Today, you have to make sure you look both ways before you cross the road. There’s that many more cars, especially in summer when the fish are in,” said Wallace.

Paula Dobbyn is a freelance journalist based in Anchorage.

©Paula Dobbyn 2013

A publication fee is required.

Contact Paula at pauladob@gmail.com

E-mail your news &

photos to editor@sitnews.us

Publish A Letter in SitNews

Contact the Editor

SitNews ©2012

Stories In The News

Ketchikan, Alaska

|

Articles &

photographs that appear in SitNews may be protected by copyright

and may not be reprinted without written permission from and

payment of any required fees to the proper sources.

|

|