Protecting School KidsBy PETER FUNT October 03, 2015

I favor more gun laws — far stricter than most liberal politicians would dare advocate in public. I abhor the NRA and the damage done by its stranglehold on our elected representatives. But I'm not so naive as to conflate gun control with crime control — especially in schools. In his frank talk to the American people immediately after the Oregon school shootings, President Obama seemed to suggest that it is our duty and his to keep revisiting these issues until something changes. These were my thoughts following the Sandy Hook massacre nearly three years ago. The arguments are just as valid today, only more urgent.

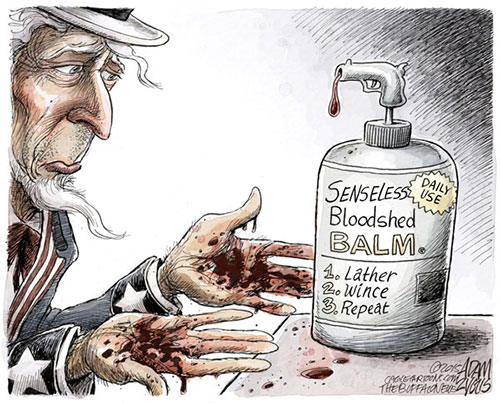

Routine Gun Violence

However, the issue of school safety goes beyond guns. When it comes to kids, what matters is protecting them while their elders struggle to find better societal solutions for maintaining their safety. Following the Sandy Hook tragedy, the notion of placing cops in schools was immediately politicized because it was among things advocated by the NRA's arch leader, Wayne LaPierre. Anything the NRA suggests is immediately challenged by gun opponents — much as any proposal to limit gun ownership is contested by Second Amendment fundamentalists. LaPierre is a lousy spokesman, even for his own cause, and his choice of words — "good guys with guns" — only serves to confuse matters when it comes to stationing police at schools. Reasonable advocates of school patrols are not proposing arming civilians, as the notorious sheriff Joe Arpaio seeks to do in Arizona. They're talking about stationing uniformed town police officers at schools, just as they are sent to patrol ballparks, malls, airports, etc. A uniformed cop should be a welcome sight, and his or her weapon should be viewed as nothing more than a piece of standard-issue equipment. Yet those who disagree with this simple logic deliberately distort the issue in their choice of words. For instance, they persist in using the term "armed guards," even though town police would never be referred to that way in routine performance of their duties. New Jersey Governor Chris Christie says having a cop on duty would make schools "armed camps." How ridiculous. More than 20 percent of the nation's public schools already have a city or town cop present, and the facilities are no more armed camps than Yankee Stadium is when New York cops patrol during games. Some say uniformed police would send the wrong message to kids. Why? Youngsters should be taught that cops are their friends — people they must rush to if they ever encounter trouble in public. Opponents make much of the fact that in 1999 a deputy stationed at Columbine High in Colorado failed to thwart gunmen who killed 12 students. But no form of police protection is perfect. Gunmen got to John Kennedy and Ronald Reagan, but that's certainly no reason to stop providing armed protection for presidents. It is often mentioned that hiring cops is expensive, especially for small communities. That's a matter of local priorities, although I would advocate a federal program to assist municipalities in paying for officers in schools. "My first choice would be to never have a gun in our schools," explained Jonathan Hornik, the Democratic mayor of Marlboro Township, New Jersey, an early advocate of placing police in schools. "But while the President and the NRA and the Congress debate policy and law, the fact is there are guns out there. How many times do we have to see these kinds of mass shootings before we decide to protect our kids?" Hornik's position is not a concession to the NRA, nor should it detract from the critical issue of gun control. If a public building were to be used to store several hundred gold bars, stationing a cop at the door wouldn't spark so much as a syllable of debate. Why do we think less of a school containing several hundred precious children?

Peter Funt is a writer and speaker. His book, "Cautiously Optimistic," is available at Amazon.com and CandidCamera.com. © 2015 Peter Funt. This column has been edited by the author. Representations of fact and opinions are solely those of the author.

|

||