Captain Walter Dibrell: Keeper of the LighthousesBy LOUISE BRINCK HARRINGTON

March 31, 2015

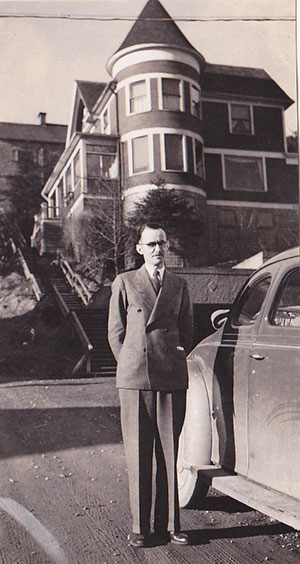

Even as a kid I loved lighthouses and with my dad would drive out to view the Guard Island Lighthouse. We'd buy ice-cream bars at Lighthouse Grocery, park at the lookout and admire the tower, the houses and gardens. My dad would talk about lighthouse keepers he'd known - one who was stationed at Mary Island and once rescued a drowning man and two Five Finger Lighthouse keepers who fought a disastrous fire in the 1930s. He also talked about Captain Dibrell, the man who was in charge of all the lighthouses in Alaska. When Dad met Captain Dibrell in 1925, the captain had an office in the Heckman building at the foot of Main Street and lived in a house at the top of the street, the castle-like home with the cone-shaped turret and golden spire that still stands today. Even after the Dibrells moved away, Dad referred to it as “the Dibrell house.” Captain Walter Dibrell purchased the place in 1916, the same year he married his wife, the former Nieta Mitchell, who was a local high school teacher and later served on the Ketchikan School Board. For a time in the early fifties I lived across the street from the Dibrells. By then Captain Dibrell had retired from his position as Superintendent of the U.S. Lighthouse Service, Alaska District. I remember the Dibrells as kind, friendly people, but unfortunately back then I did not take the time to talk to them about the Alaska lighthouses. Now I wish I had. Recently I did some research to learn more about Captain Dibrell and his history.

When he arrived in Ketchikan in 1913, Walter Crockett Dibrell was not new to town. He’d been born in Texas in 1875, graduated from the University of Texas in 1900 and received an appointment to the U.S. Coast and Geodetic Service, becoming captain of the survey-ship Explorer. He and his ship first stopped in Ketchikan in 1907 - then again in 1908, 1909 and 1910. In 1912 he transferred to the then-newly-formed U.S. Lighthouse Service and was promoted to Superintendent of the Sixteenth District, which included all of Alaska. The district headquarters were located at Ketchikan. At the time, sea-going conditions along the Alaska coast were dangerous, to say the least. “Alaska has a wicked coastline, broken and battered with bold outlying ridges, and inside passages, bristling with sharp turns and jagged headlands of the kind that give ship pilots gray hair long before their time,” wrote historian James A. Gibbs in his book “Lighthouses of the Pacific.” The new Lighthouse Service headquarters, such as they were, stood on Ketchikan's waterfront about where Talbot's is now - basically a small wharf and rundown warehouse. By 1919 Dibrell had succeeded in moving the headquarters to a larger piece of federally-owned land, located where the Coast Guard base is today. There he began the construction of a concrete two-story administration building, shop, buoy depot, wharf and marine ways. (This was the beginning of the U.S. Coast Guard Base that we know today.) Also by 1919 Dibrell was supervising eleven Alaska light stations, seven in Southeast and four to the north and westward. And he visited each station at least once a year.

The Guard Island Lighthouse was the closest and easiest to supervise, situated only nine miles or so from Ketchikan at the northwestern entrance to Tongass Narrows. The original station had been built in 1903 after many complaints from local mariners that they had to proceed “with a speed of three knots and a fervent prayer” because the Narrows were so difficult to navigate.

But as the years passed, continual wet weather took a toll on the old wooden light tower. In 1922 Dibrell had it replaced with a new concrete structure and added a second keeper's house so that two keepers and their families could reside on the island. Keeper George West and his wife Alma lived in one of the two houses during the infamous bootlegging days of the late 1920s. One day when Keeper West was away and Alma left in charge, a double murder took place. Alone at the station, Alma West looked out the window and saw two boats maneuvering off the southern point of the Cleveland Peninsula. Squinting through binoculars, she watched for some time, sensing that something dastardly was going on. She kept her eye on the boats and hours later one of them drifted near the shoreline of Guard Island. When Mr. West returned, he boarded the pilot-less boat and found two dead bodies on the cabin floor. It appeared that one man had tried to rob the boat's safe, while the other man struggled to stop him. A bloody battle ensued, during which the two men inflicted deadly wounds on each other. During an inquest into the deaths, George and Alma West both testified. So did a federal agent, who reported that hairs from one man's head were found under the fingernails of the other and that the boat's safe contained a considerable amount of cash. It was, of course, well-known to Dibrell and others in town that both men had been buying and selling Canadian booze. The two apparently fought it out and succeeded in killing each other over bootleg money. As if a double murder near Guard Island was not enough, another murder occurred when an illicit love affair developed between the station's head keeper and the assistant keeper's wife. The affair had been going on for some time, when discovered by the assistant keeper. When it came time for his next vacation, the assistant keeper took his wife on a trip to Seattle, where they checked into a hotel room and she was later found dead in a pool of blood. Details of the case remain murky to this day because Dibrell did his best to hush up the scandal and avoid causing harm to the families involved, as well as the Lighthouse Service itself. It was concluded in court, however, that the assistant keeper had murdered his wife during a fit of jealous rage.

Dibrell made his yearly lighthouse inspection trips aboard the lighthouse tender Cedar, which was home-ported in Ketchikan and captained by John W. Leadbetter. Early each summer, the Cedar would depart Ketchikan and steam first to the light stations at Scotch Cap and Cape Sarichef in the Aleutian Islands. Then she would make her way across the Gulf of Alaska to the Cape St. Elias and Cape Hinchinbrook stations and from there head back south, stopping at each light along the southeastern coast, returning to Ketchikan in the late fall. On one such trip disaster struck the Cedar in the form of the shipwrecked Canadian Pacific steamship Princess Sophia. The Cedar was making her way home, when Captain Leadbetter received a distress call from the Princess Sophia, reporting that she had run aground on Vanderbilt Reef. Several wireless messages were sent from the Cedar to the Sophia, as well as to the Lighthouse Service in Ketchikan. Dibrell himself relayed the final message, reporting that steamer Sophia had gone down, taking all her passengers and crew members with her. The crew of the Cedar spent several days exploring nearby waterways and walking the beaches in a desperate search for bodies.

The CEDAR and Crew

At one point some litigants attempted to blame the Lighthouse Service and Captain Leadbetter for not providing more assistance to the stricken Sophia. Although this accusation was false—as the captain did everything he could in a difficult situation—Leadbetter traveled to Seattle to testify at the trial. Because he had firsthand knowledge of the wreck and seen it with his own eyes, he was able to give straightforward, accurate testimony and set the record straight. Dibrell, of course, did all he could to lend support to Captain Leadbetter and protect the reputation of the U. S. Lighthouse Service. Thankfully, most trips aboard the Cedar were less eventful and more enjoyable for all concerned. Dibrell especially enjoyed the travel when his wife Nieta and their young son David McDonald Dibrell, who was born on October 7, 1919, could join him.

During the summer of 1931 the Cedar towed a loaded barge from Valdez to Hinchinbrook Island, located near the entrance to Prince William Sound, where construction of a new replacement lighthouse had been in the planning stage for months. Built on a high cliff, the original Cape Hinchinbrook Light Station had been damaged by a series of earthquakes that sliced off parts of the cliff, leaving the light tower broken and barely standing on the edge. This alarmed and worried Dibrell, who requested federal funding that - as was usually the case - took years to materialize.

First Cape Hinchinbrook Light Station With the project finally underway, the Cedar and barge now carried construction supplies that included an air compressor, concrete mixer, lumber for a bunkhouse and roofing paper and tar. Everything had to be unloaded into smaller boats that could maneuver through the minefield of submerged rocks and reefs that surround Hinchinbrook Island. The supplies then had to be hauled up the cliff to the work camp above, using a hoist and winch as well as many strong backs. During the second year of work on Hinchinbrook, 1932, Dibrell watched as the crew poured footings for the new tower foundation. At this point he felt encouraged and enthusiastic, according to a letter he wrote to a friend. But shortly thereafter the funding ran out, forcing a work stoppage and camp closure. Frustrated, he requested additional federal funds, but they did not come through until 1933. Construction again resumed in May of that year.

Second Cape Hinchinbrook Light Station

The original lantern and lens—amazingly still in good shape—were transferred from the old tower to the new. As soon as the light was lit, a bulldozer unceremoniously pushed the old structure off the cliff into the sea!

On December 9, 1933, a fire broke out at Five Finger Island Lighthouse, located in Stephens Passage about 155 miles north of Ketchikan. While trying to thaw frozen water pipes with a gasoline torch, one of the keepers accidentally set fire to a wall. Two of the station's keepers attempted to fight the blaze (the third keeper was away on vacation). Luckily, the Cedar happened to be standing by, unloading supplies, and her crew rushed ashore to help. But with no water available due to the frozen pipes, the flames quickly spread to surrounding buildings and the entire station went up in a blazing inferno. The Cedar radioed Ketchikan, informing Dibrell that the station had been destroyed and everything was gone—the radio beacon, the light beacon, the keepers' quarters, fog signal, all of it. The only good news was that no one was hurt.

First Five Finger Islands Lighthouse The total cost came to $90,000.

“Don't think, especially ghoulish thoughts. More importantly, don't think at all unless it's about your job.” Believe it or not this was some of the first advice given to newly-hired Lighthouse Service keepers. The months and years of isolation and loneliness proved too difficult for some who fell victim to strange solitary thoughts that actually drove them mad. Probably the worst part of Dibrell's job was having to remove a keeper from his position because of mental instability. One keeper at Cape Sarichef, a lighthouse on remote Unimak Island, had to be removed because he constantly babbled about the ghosts of Aleuts who'd been murdered by the Russians and now haunted the island. The keeper's rants were so destructive they were driving his fellow keeps crazy, too.

Cape Sarichef Dibrell was forced to visit one lighthouse in order to referee between three keepers who were not crazy, but had stopped speaking to each other for a crazy reason. The problem started with an argument about potatoes—whether they should be boiled or mashed or fried—and progressed from there. Other disagreements arose over the rationing of tobacco and cigarettes when supplies ran low. Years ago one of my mother's friends, Marjorie Anderson Hansen, visited and told us about an old retired keeper, who would walk the streets of Ketchikan and try to wave away imaginary bugs that he saw floating in the air around him. Folks around town would shake their heads and say, “That poor old guy spent too damn much time at the lighthouse!”

Cape Decision is a dark, dangerous, rock-studded place where the Gulf of Alaska meets Chatham Strait. During the early days, the cape claimed so many ships and lives that a small acetylene light was set up in a feeble effort to aid mariners.

Cape Decision Although frequent storms hammered the area and hindered progress, by 1930 the site on the southern tip of Kuiu Island had been leveled and a camp building set up. Next, the crew constructed a dock and tramway, installed a derrick and hoisting machinery, then started building the boathouse. Finally in March, 1932, all buildings were finished and the brand-new first-class station activated. It boasted a flashing 350,000 candlepower electric light that shone 96 feet above the water. It also had a compressed-air fog signal, a Class A radio beacon, and housing for three keepers. The total cost of construction came to $158,000. Cape Decision was the last lighthouse ever to be built in Alaska.

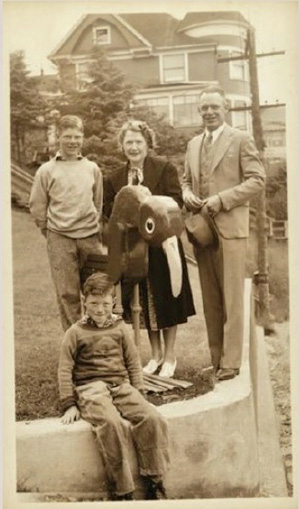

Near the end of 1939 the U.S. Coast Guard took over and absorbed the old U.S. Lighthouse Service. At this point, after thirty-three years of government service, Dibrell retired. During his tenure, he'd supervised the building or re-building of 16 Alaska light stations and established more than 1500 navigational aids, including shore lights, buoys and beacons. Soon after his retirement a position opened on the Ketchikan Public Utilities Board of Control, friends encouraged him to apply and he gave the idea serious thought. After much consideration and with World War II looming, he concluded that serving on the board would be a worthwhile contribution to the war effort. But soon after his appointment, he began to realize that community service would be more difficult than he'd expected. “Performing public service in a small community brings much in the way of grief,” he wrote in a letter to a friend. “I can sympathize with others who accept public office.” Much of Dibrell's frustration revolved around development of the new George Inlet/Beaver Falls power project, located about eleven miles from Ketchikan. Along with the KPU manager and two other board members, he hiked to both Lower and Upper Silvis Lakes to inspect and explore the area. He concluded that the natural lake setup was ideal for a small power facility and although the initial output would be only 1500 to 1800 KW, he believed it had the capacity for three times that amount. “But we have encountered opposition and many discouraging difficulties and delays,” he wrote in 1945. After three additional years of opposition, argument and frustration, the board finally signed an agreement and awarded a contract for the building of a plant at Beaver Falls. Other projects that came to fruition during Dibrell's time on the utility board included the replacement of 1210 feet of water main on Tongass Avenue; the rebuilding of the main on Park Avenue; and the purchase and installation of new telephone lines and equipment. After retiring from the board in 1946, he devoted his time to working on his Main Street house and garden, building backyard playground equipment for the neighborhood kids and volunteering at the Methodist Church down the street. During this time he also carved the very first incarnation of the iconic and beloved Ketchikan Rainbird! The Dibrells remained in Ketchikan until 1962, when they sold their castle-like home and moved to Coleman, Texas. When he died on January 16, 1982 at the age of 106, the state of Alaska issued a proclamation in his memory. It read in part: “He left behind 16 lighthouses and more than 1500 shore lights and buoys, which shall remain as silent monuments of maritime safety. A part of that era has gone with hard-working and courageous pioneer Alaskan.” What a fitting final tribute to Captain Walter Dibrell, the man who devoted so many years to being the keeper of Alaska’s lighthouses!

Sources:

Acknowledgement:

Louise Brinck Harrington is an author and freelance writer living in Ketchikan, Alaska. All rights reserved, Lousie Brinck Harrington ©2015

|

||||