“Black Matt” Berkovich and Son Nick: A Ketchikan StoryBy LOUISE BRINCK HARRINGTON

August 19, 2015

Murder and Suicide The “grand finale” took place in the Mint Pool Hall, located in Ketchikan near the corner of Stedman and Mission Streets. The Mint was a combination pool hall, card room and barber shop. “The place where Gentlemen meet and Headquarters for all Sourdoughs,” read an ad that ran in local newspapers. Matt held a mortgage on the building and liked to frequent the place, and that’s where he pulled a .38 automatic from his pocket and pumped three shots into his former accomplice, Phil Dohm, who died instantly.

“Matt, what are doing?” Matt swung on him and ordered, “Sit down and shut up, or you’ll get it too.” Matt placed a letter on the cigar counter. “Give this to my son Nick,” he instructed his friend Ben Schoen, who stood behind the counter. Then he turned the gun to his temple, pulled the trigger and blew his brains out, according to the Ketchikan Tribune of December 12, 1930. Immediately after the shooting crowds gathered along Stedman Street. Angry voices rose, demanding revenge and retaliation. There were those who hated Matt and believed he stood for pure unadulterated evil, and those who thought he was not so bad and even considered him a friend. As the two sides grew more violent, fights broke out and U. S. marshals patrolled the streets. They rounded up the men who testified against Matt, took them to jail and locked them up - for safekeeping! The telephone switchboard lit up like never before in Ketchikan. All available telephone operators, including the supervisor, worked all night fielding hundreds of calls. Everyone in town wanted to know what happened and express an opinion, pro or con. The next day the Ketchikan Alaska Chronicle headlined in big black print: “Black Matt Kills Phil Dohm, Chief Witness against Him, Then Suicides.” Another headline screamed: “Whole Town Stirred by Dramatic Killing!”

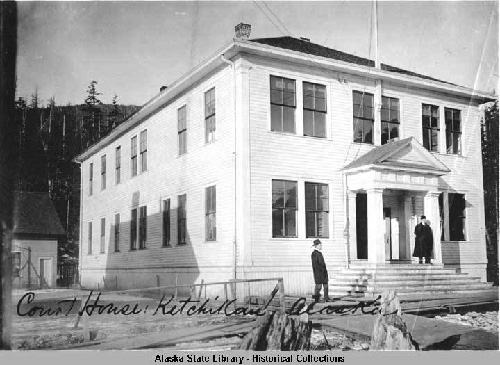

Ketchikan Waterfront - Early 1920s The Evil and the Good Although nationally Prohibition took effect with the passage of the Volstead Act in 1920, Alaska “went dry” with the passage of the “Bone Dry Law” in 1918. By this time Matt had lived in Ketchikan for at least seven years and knew most people, especially those in the underworld. As the demand for bootleg-booze grew he was in a position to profit. He owned property both on Water Street near the Lighthouse Depot and on Stedman Street near the boat harbor, where small boats and skiffs could glide in and out under the dark of night. Additionally, he owned at least three boats big and sturdy enough to make the 180-mile-roundtrip to Prince Rupert, British Columbia, which of course was not subject to U.S. Prohibition laws and remained “wet.” He counted among his friends more than one or two government officials who could be bribed, either with bottles of booze or rolls of greenbacks. Wink, wink, and the officials happily turned a blind eye to Matt’s underworld activity—which in addition to bootlegging included gambling and prostitution, both of which flourished in his buildings. Clearly “the big Slavonian” had no problem breaking the law if it benefitted him and his bank roll. On the other hand, he was not completely evil; he had a few redeeming qualities. One was showing kindness to old fishermen that he met hanging around Thomas Street and the boat harbor. Many of the old-timers struggled to survive on next to nothing and had nowhere to live. Matt would provide a cabin or shack and charge only a dollar a year for rent. If a friend from “the old country”—Matt’s birthplace which was then called Dalmatia and is now part of Italy—needed a job or a business, Matt usually found him one. He helped Mitchell Bilicich and Tony Budinich establish restaurants, and Pete Lucey and Ben Schoen with jobs at the Mint. If Matt’s family needed anything, he was big-hearted. Before his death, he made sure to provide for his aging father back in Dalmatia. “Please send to my father in the old country $100 every three months for his living,” he instructed his son Nick Berkovich in a letter before his death. “The money comes from the rent I get on these houses. Write him that I died, nothing else.” In other letters he expressed love for his father, his two deceased wives, and his son and daughter-in-law. The Trial In November of 1930 the law caught up with Matt. He and his accomplice, Phil Dohm, were arrested and charged with conspiracy to violate the National Prohibition Act. Shortly thereafter Dohm, in order to save his own skin, turned state’s evidence, joined the prosecution and testified against Matt before the Grand Jury. Within a few weeks, the case went to trial. The U. S. Courthouse, then located on the Grant Street hill, was packed to the rafters, according to newspaper accounts. Witness after witness took the stand and told of dealings and transactions and travels with Matt - all regarding booze. Many also testified that Matt talked often and openly about “protection” and “fixing” and his “gang on the hill.”

Court House; Ketchikan, Alaska

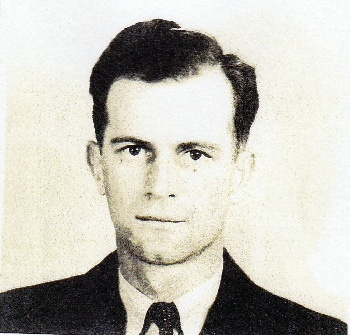

Other witnesses described the “cargo,” which was usually transported in gunny sacks. Sometimes, with U. S. marshals hot on their tail, the bootleggers would stash the “cargo” at some out-of-the-way cove and return for it later. Sometimes, if things were really hot, they would even—with much regret—be forced to throw the booze-laden sacks overboard! In describing the first day of the trial, the Ketchikan Alaska Chronicle quoted U. S. District Attorney H. D. Stabler who said: “There is evidence of the right cross, the left cross, the grand cross, and the double cross in the bootlegging circles of Ketchikan.” The following day the newspaper reported that Stabler’s assistant, George Folta, claimed that some witnesses had been referred to as “rats,” but that Matt Berkovich was “even lower than the rats and can’t even join the rats.” Folta added that Matt’s biggest problem was “hoof-and-mouth disease” because he talked and bragged too much about “paying for protection.” The newspaper also reported that during the trial Matt’s attorneys, A. H. Ziegler and George Grigsby, objected to almost everything that was offered by the government, while Stabler and Folta were on their feet constantly, objecting to everything put forward by the defense. What a lot of grand-standing and showmanship! Near the end Matt himself took the witness stand, denied every word that every witness said against him, and pleaded his innocence. But he was doomed. He could not convince the jury, the members of which had made up their minds and voted to convict him. For the conviction and all the legal trouble, Matt placed the blame squarely on Phil Dohm, his former side-kick. “This man I’m taking with me framed me and put me in this trouble,” he wrote shortly before the murder-suicide. “I’m going to be the last man he frames.” Son Nick Berkovich A month before his death, Matt transferred all his properties (including the Mint, which he acquired due to a large unpaid loan to the former owner) to his son, Nick. At the time Nick, 27, and his wife Edna, 20, were living in Tacoma, Washington. Upon his father’s death Nick and his wife moved to Ketchikan, settled into one of the Thomas Street houses and began managing Matt’s estate and properties.

Seiners: Crest, of Seattle, and Anita, of Ketchikan, at Ketchikan City Float July 20, 1954

The photo shows the Anita backing out of her berth with Nick Berkovich's Crest and the Selma following.

He then bought a boat and became a commercial fisherman.

In 1932 he and Edna started a family. Their first son, Matthew, was born that year, followed by Nick Jr. in 1940 and Larry in 1943. Nick strove to improve his neighborhood and community. In 1939 he spoke to the Ketchikan City Council about the “beer parlors, cocktail lounges and clubs along Stedman Street” that left their doors open, subjecting women and children to “vile language,” according to City Council minutes. He said that the clubs should be regulated and nighttime noise reduced. In addition, he let the council know that Stedman Street itself needed improvement - it was uneven, rutted and hazardous in places. Also, there were adjacent alleys and boardwalks that needed work. And some property owners should be fined for not maintaining their buildings and allowing them to fall into disrepair. Fish Traps and “Spawn of the North” As a fisherman Nick resented the fish traps that were owned and operated by big cannery interests. The traps caught thousands of fish, which not only depleted the resource, but made it nearly impossible for an individual fisherman to compete. Believing the solution was independence for Alaska, Nick joined the growing statehood movement. Give Alaskans control of their own resources!

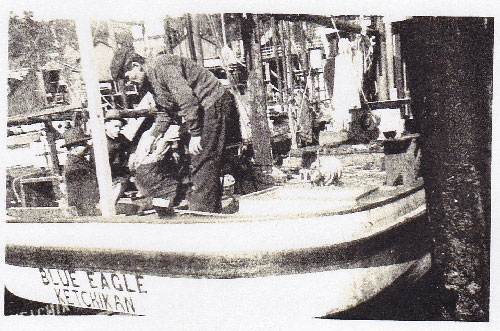

Nick Berkovich's boat, The BLUE EAGLE, ws used in the movie “Spawn of the North"

In 1949 Edna Berkovich bought a home in Seattle and the family moved. Nick, however, retained his Ketchikan residency and much of his property. Although living in Seattle, he returned each year for the commercial fishing season. He did not retire from fishing until 1977. When Nick died in Seattle in 1978, his obituary focused on his life and time in Ketchikan. No mention was made, however, of his infamous father, the “big Slavonian” as the Wrangell Sentinel referred to him. Nor was anything said about bootlegging or underworld crime or, of course, the “grand finale.”

Related Features:

On the Web:

Louise Brinck Harrington is an author and freelance writer living in Ketchikan, Alaska. All rights reserved, Lousie Brinck Harrington ©2015

|

|||